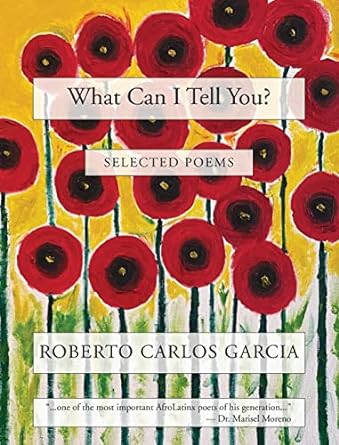

What Can I Tell You (Selected Poems) by Roberto Carlos Garcia's

Reviewed by Jordan E. Franklin

Remixing Expectation:

If you follow writers on social media, hopefully you have been fortunate enough to become familiar with the founder of Get Fresh Books, Roberto Carlos Garcia, a generous poet and educator unafraid to delve into the cultural zeitgeist, to tackle taboos or to champion the works of other poets and artists alike.

In What Can I Tell You, his first compilation of selected works, Garcia’s

musicality and raw language invite us in, guides us, as if we are sharing a set of headphones to experience his Afro-Latine voices. He is the ultimate conductor, deftly treating us to a harmonious exploration of family, grief, race, identity, mental health and survival.

The first book in Garcia’s Selected, Melancolía, the title which roughly translates to “depression” or “melancholy,” is a refreshingly honest take on his struggles with depression and the accompanying stigma with which the African American and Latine communities fetter discussions about mental health. In “Melancolia", one of the titular poems, Garcia is both bold and vulnerable, treating readers to his trademark introspective style:

Husband, father, son–

but in the sun I cry easily

like a child lamenting a fallen ice cream cone,

the fine line between caring and catatonia

dust in a sun ray.

This stanza, along with the rest of the poem, is an exploration of Garcia’s depression, its roots and how it shapes his relationship to the larger world. In our society, men are supposed to be stoic, unflappable and unemotional; any vulnerability is seen as a weakness and a contradiction to “masculinity.” In the first line, Garcia reaffirms his masculinity as he breaks down his identity. He is a father, a husband, and a son. These connections, however, aren’t enough to stave off his feelings of sadness over his perceived insignificance; Garcia is explicit about his reaction to these feelings, revealing that they make him cry, reminiscent of “a child lamenting a fallen ice cream cone.” The usage of this familiar image, rather than minimizing his depression, makes it something tangible and relatable to the reader, stressing that depression is commonplace, but also something that must be acknowledged and overcome with effort.

The second book, black/Maybe: An Afro Lyric, offers the reader more insight into Garcia’s background as an Afro-Latine poet in the United States. This book utilizes both personal and historical lenses. Part-verse, part-prose and even part-play, poems in this portion of the collection explore tensions between members of the Afro-Diasporic community (African-American, Afro-Caribbean, Afro-Latine), particularly amongst the Dominican and Haitian populations. In the titular essay “black Maybe,” Garcia meditates on Blackness and identity across national, cultural, and generational lines, “As I got older, I began to recognize the differences between African American culture, Afro-Latine culture, and being black in between. Black being the giant labels America puts on anyone darker than a paper bag.” As a Black writer whose family tree includes Central and West Indian American roots, Garcia’s poignancy in speaking of his dilemma is especially sharp. Not only does he reference the racial struggles rampant in the Dominican Republic, he also highlights the colorism and racism prevalent in North American culture. I did not learn about the “brown paper bag” test–a way to gauge the acceptability of one’s skin color–until I was older. To see it referenced here not only jarred me but filled me with a deep sadness reminding me of the contradictory nature of the United States, a place where one’s freedom and worth are dependent upon one’s proximity to whiteness.

The third book, [Elegies], contains poems befitting its title. Each piece is a meditation on loss, support and understanding where Garcia’s father and grandmother are frequent visitors. In “Elegy for My Pop” the touching father-son tribute explores a bittersweet reality:

In the real world we don’t know each other

& he says as much.

This dream–I’m an unknown man gifting

forgiveness to an unknown man.

Traditionally, elegies honor the passing of a person or thing. This poem, despite being only eleven lines long, both honors and defies the elegiac tradition. The father figure in question is both mourned and challenged by the speaker who acknowledges the father’s failure to be “present” in the speaker’s life. Garcia's elegy follows in the tradition of Sylvia Plath's "Daddy" and lucille clifton's "forgiving my father," two poems that use the elegy form to express anger at the speakers' deceased fathers. The true “loss” here is questionable which adds another layer to the poem: Is the speaker mourning the lost father or the lost relationship?

What Can I Tell You? shows readers that poets can be historians, painters, musicians, comedians, and activists. Garcia embodies entire disciplines in his lyrics. This collection serves as both a greatest hits and a promise for the future, assuring readers that Garcia is a poet that challenges genre with creativity, depth, and a profound feeling of justice.

If you follow writers on social media, hopefully you have been fortunate enough to become familiar with the founder of Get Fresh Books, Roberto Carlos Garcia, a generous poet and educator unafraid to delve into the cultural zeitgeist, to tackle taboos or to champion the works of other poets and artists alike.

In What Can I Tell You, his first compilation of selected works, Garcia’s

musicality and raw language invite us in, guides us, as if we are sharing a set of headphones to experience his Afro-Latine voices. He is the ultimate conductor, deftly treating us to a harmonious exploration of family, grief, race, identity, mental health and survival.

The first book in Garcia’s Selected, Melancolía, the title which roughly translates to “depression” or “melancholy,” is a refreshingly honest take on his struggles with depression and the accompanying stigma with which the African American and Latine communities fetter discussions about mental health. In “Melancolia", one of the titular poems, Garcia is both bold and vulnerable, treating readers to his trademark introspective style:

Husband, father, son–

but in the sun I cry easily

like a child lamenting a fallen ice cream cone,

the fine line between caring and catatonia

dust in a sun ray.

This stanza, along with the rest of the poem, is an exploration of Garcia’s depression, its roots and how it shapes his relationship to the larger world. In our society, men are supposed to be stoic, unflappable and unemotional; any vulnerability is seen as a weakness and a contradiction to “masculinity.” In the first line, Garcia reaffirms his masculinity as he breaks down his identity. He is a father, a husband, and a son. These connections, however, aren’t enough to stave off his feelings of sadness over his perceived insignificance; Garcia is explicit about his reaction to these feelings, revealing that they make him cry, reminiscent of “a child lamenting a fallen ice cream cone.” The usage of this familiar image, rather than minimizing his depression, makes it something tangible and relatable to the reader, stressing that depression is commonplace, but also something that must be acknowledged and overcome with effort.

The second book, black/Maybe: An Afro Lyric, offers the reader more insight into Garcia’s background as an Afro-Latine poet in the United States. This book utilizes both personal and historical lenses. Part-verse, part-prose and even part-play, poems in this portion of the collection explore tensions between members of the Afro-Diasporic community (African-American, Afro-Caribbean, Afro-Latine), particularly amongst the Dominican and Haitian populations. In the titular essay “black Maybe,” Garcia meditates on Blackness and identity across national, cultural, and generational lines, “As I got older, I began to recognize the differences between African American culture, Afro-Latine culture, and being black in between. Black being the giant labels America puts on anyone darker than a paper bag.” As a Black writer whose family tree includes Central and West Indian American roots, Garcia’s poignancy in speaking of his dilemma is especially sharp. Not only does he reference the racial struggles rampant in the Dominican Republic, he also highlights the colorism and racism prevalent in North American culture. I did not learn about the “brown paper bag” test–a way to gauge the acceptability of one’s skin color–until I was older. To see it referenced here not only jarred me but filled me with a deep sadness reminding me of the contradictory nature of the United States, a place where one’s freedom and worth are dependent upon one’s proximity to whiteness.

The third book, [Elegies], contains poems befitting its title. Each piece is a meditation on loss, support and understanding where Garcia’s father and grandmother are frequent visitors. In “Elegy for My Pop” the touching father-son tribute explores a bittersweet reality:

In the real world we don’t know each other

& he says as much.

This dream–I’m an unknown man gifting

forgiveness to an unknown man.

Traditionally, elegies honor the passing of a person or thing. This poem, despite being only eleven lines long, both honors and defies the elegiac tradition. The father figure in question is both mourned and challenged by the speaker who acknowledges the father’s failure to be “present” in the speaker’s life. Garcia's elegy follows in the tradition of Sylvia Plath's "Daddy" and lucille clifton's "forgiving my father," two poems that use the elegy form to express anger at the speakers' deceased fathers. The true “loss” here is questionable which adds another layer to the poem: Is the speaker mourning the lost father or the lost relationship?

What Can I Tell You? shows readers that poets can be historians, painters, musicians, comedians, and activists. Garcia embodies entire disciplines in his lyrics. This collection serves as both a greatest hits and a promise for the future, assuring readers that Garcia is a poet that challenges genre with creativity, depth, and a profound feeling of justice.

Jordan E. Franklin is a poet from Brooklyn, NY. She is the author of the full-length poetry collection, when the signals come home (Switchback Books), and a poetry chapbook, boys in the electric age (Tolsun Books). Her work has appeared in Breadcrumbs, Frontier, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, the Southampton Review and elsewhere. She is the winner of the 2017 James Hearst Poetry Prize, the 2020 Gatewood Prize, and a finalist of the 2019 Furious Flower Poetry Prize. Currently, she is a doctoral candidate and Clark fellow at Binghamton University.