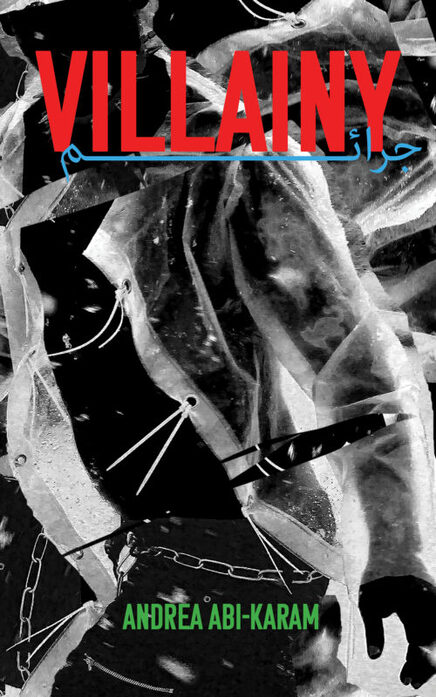

Revelry of Queerness & Desire: Villainy by Andrea Abi-Karam

Reviewed by Benjamin Grimes

Name your desires, reader—the large and looming, seemingly constant; or the small, the shifting, dependent on the time of day, the where, the what, the who—all the points of desire along a line approaching the singularity that is Desire. But let’s stylize it as DESIRE: for the who is Andrea Abi-Karam, the what is Villainy, and the DESIRE is to be screamed at and spit on and slapped into ecstasy—desires that perhaps you, and certainly I, did not know we had.

Before reading Villainy, voicing such desires might have made me embarrassed or ashamed—but Abi-Karam’s work challenges the concept of shame, evoking a beautiful lack thereof. Though set against the staggering violence of the U.S. police state, this book is a celebration, “A TRANSFUSION OF GLAM,” “A FULL BLOWN / REVELRY OF QUEERNESS & DESIRE THAT WE HAVE ONLY NOW / JUST BARELY BEGUN TO IMAGINE,” as lines from the opening pages declare. Abi-Karam’s poems combat the omnipresence of state violence and control by stealing and celebrating any moments of desire they can find. If normative gender and sexual constructs constrain our bodies, if by enforcing these constructs the broader society assaults our bodies, then perhaps queerness is the only way out.

Across the collection, Abi-Karam searches for what they might call a temporary autonomous zone—both large-scale spaces, like the brief experiments in self-governance that we saw in Seattle, Portland, and elsewhere in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests last summer, and smaller, more intimate moments in which to reimagine how we use, play, or simply exist in public (i.e. policed) spaces. In the untitled prelude to the collection, the speaker creates one such autonomous zone:

You fuck me with your entire hand in a room full of the dead. The dead

are inside boxes behind glass. You fuck me so we can feel for one second

that our friends are not dead. That they are living inside of us. A security

guard approaches & you stop. I pull you up from the floor by the lapels

of your leather jacket. Face covered in cum. I exhale & absorb our dead

friends into my body like you opened up a gateway for their arrival.

Though grief is ever-present in Abi-Karam’s world—which is also our world, dedicated to violent control over queer spaces and bodies—present, too, is the possibility of community, connection, ecstasy. Villainy is an ambitious project, and one of the ambitions is, to borrow from the book’s Paul B. Preciado epigraph, “to open a revolutionary terrain for the invention of new organs & desires.” For Abi-Karam, the urgent question is not what we will find, but how we will get there.

One way Abi-Karam proposes to reach this revolutionary terrain is through “unbecoming,” a recurrent theme throughout the book. To free oneself of the forms and walls, the laws and outlines of an oppressive society, Villainy’s speaker strives to become formless, to push beyond their edges “to the layer beneath / where our connections to each other / become more visible.” Sweat- and cum-covered bodies form crowds of orgy or protest (is there a difference?), affirming their power and pleasure. But unbecoming is not without an inherent tension, an uncertain outcome:

WHAT ARE WE EVEN / WITHOUT OUR EDGES / WITHOUT

OUR OUTLINES!

HOW DO WE MAINTAIN THEM AGAINST ALL POSSIBLE

VIOLENCES

HOW DO WE STAY W/HOLE

Is it possible to be pushed beyond the edges by society, to move beyond the limits of our individual bodies, and still remain whole? If so, as the section titled “AN UNBECOMING” makes clear, we will get there by imagining. Abi-Karam exhorts us again and again to “Imagine the possibility of unbecoming”—an imperative that I like reading in two ways: imagine unbecoming as a possible outcome, and imagine the possibility inherent in the act of unbecoming. The latter speaks directly to Abi-Karam’s work and thinking as an abolitionist—one who imagines the creative possibility and potential for a new world through the unmaking of the current one.

What role can poetry play in the work of radical activism and progressive movements? It is an old question, one in which Abi-Karam is clearly invested. “can we even / think of arts as a form of militancy,” the speaker asks in the first section, “THE AFTERMATH,” before continuing:

—& i’m very much conflicted on

this too

like i want to & i do but also with the understanding that it’s not enough

& really has to arrive out of a moment of upheaval or conflict or

feeling & can’t actually be predictive

that’s why the fighting phase

that’s why i’m not sure i trust the fighting phase

Through repetition and unadorned language—techniques favored across the collection—the speaker almost argues with themself, and even begins to interrupt themself with questions like “WOULDN’T AWFUL DOGMA BE SUCH A GOOD ALBUM NAME,” rather than settle on any definitive answer.

Besides, why insist on some vast distance between radical words and radical actions, anyway? Reading Villainy, I have the sense of a poet who is always working, observing, writing—a poet for whom “a different kind of march” where “we don’t steal anything / just space on the street—temporarily,” is just as much poetry, just as much protest as the “hot tub orgy / a few days later.” This is a poet who takes you on a walking tour of their city, pointing out the parts they still recognize, introducing you to their friends and influences along the way. Reading such a poet is an experience of extreme presence—so much so that when they say “hold my hand through the flash bangs / & i’ll hold yrs thru the flogging,” you might just offer in return a small promise to the pages in your hands.

The walking, the searching, the questioning continues in the final section of the book, “‘Poetry as Forces,’” a piece in conversation with artist and activist Cecilia Vicuña. The speaker asks, “how do we weaponize ourselves / how to weaponize the poem.” Here the conversational mode has been abandoned for fragments, short lines, blunt language, as if the speaker is ready to put down their pen and head back out into the streets. Reader, you may just have to join them.

Before reading Villainy, voicing such desires might have made me embarrassed or ashamed—but Abi-Karam’s work challenges the concept of shame, evoking a beautiful lack thereof. Though set against the staggering violence of the U.S. police state, this book is a celebration, “A TRANSFUSION OF GLAM,” “A FULL BLOWN / REVELRY OF QUEERNESS & DESIRE THAT WE HAVE ONLY NOW / JUST BARELY BEGUN TO IMAGINE,” as lines from the opening pages declare. Abi-Karam’s poems combat the omnipresence of state violence and control by stealing and celebrating any moments of desire they can find. If normative gender and sexual constructs constrain our bodies, if by enforcing these constructs the broader society assaults our bodies, then perhaps queerness is the only way out.

Across the collection, Abi-Karam searches for what they might call a temporary autonomous zone—both large-scale spaces, like the brief experiments in self-governance that we saw in Seattle, Portland, and elsewhere in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests last summer, and smaller, more intimate moments in which to reimagine how we use, play, or simply exist in public (i.e. policed) spaces. In the untitled prelude to the collection, the speaker creates one such autonomous zone:

You fuck me with your entire hand in a room full of the dead. The dead

are inside boxes behind glass. You fuck me so we can feel for one second

that our friends are not dead. That they are living inside of us. A security

guard approaches & you stop. I pull you up from the floor by the lapels

of your leather jacket. Face covered in cum. I exhale & absorb our dead

friends into my body like you opened up a gateway for their arrival.

Though grief is ever-present in Abi-Karam’s world—which is also our world, dedicated to violent control over queer spaces and bodies—present, too, is the possibility of community, connection, ecstasy. Villainy is an ambitious project, and one of the ambitions is, to borrow from the book’s Paul B. Preciado epigraph, “to open a revolutionary terrain for the invention of new organs & desires.” For Abi-Karam, the urgent question is not what we will find, but how we will get there.

One way Abi-Karam proposes to reach this revolutionary terrain is through “unbecoming,” a recurrent theme throughout the book. To free oneself of the forms and walls, the laws and outlines of an oppressive society, Villainy’s speaker strives to become formless, to push beyond their edges “to the layer beneath / where our connections to each other / become more visible.” Sweat- and cum-covered bodies form crowds of orgy or protest (is there a difference?), affirming their power and pleasure. But unbecoming is not without an inherent tension, an uncertain outcome:

WHAT ARE WE EVEN / WITHOUT OUR EDGES / WITHOUT

OUR OUTLINES!

HOW DO WE MAINTAIN THEM AGAINST ALL POSSIBLE

VIOLENCES

HOW DO WE STAY W/HOLE

Is it possible to be pushed beyond the edges by society, to move beyond the limits of our individual bodies, and still remain whole? If so, as the section titled “AN UNBECOMING” makes clear, we will get there by imagining. Abi-Karam exhorts us again and again to “Imagine the possibility of unbecoming”—an imperative that I like reading in two ways: imagine unbecoming as a possible outcome, and imagine the possibility inherent in the act of unbecoming. The latter speaks directly to Abi-Karam’s work and thinking as an abolitionist—one who imagines the creative possibility and potential for a new world through the unmaking of the current one.

What role can poetry play in the work of radical activism and progressive movements? It is an old question, one in which Abi-Karam is clearly invested. “can we even / think of arts as a form of militancy,” the speaker asks in the first section, “THE AFTERMATH,” before continuing:

—& i’m very much conflicted on

this too

like i want to & i do but also with the understanding that it’s not enough

& really has to arrive out of a moment of upheaval or conflict or

feeling & can’t actually be predictive

that’s why the fighting phase

that’s why i’m not sure i trust the fighting phase

Through repetition and unadorned language—techniques favored across the collection—the speaker almost argues with themself, and even begins to interrupt themself with questions like “WOULDN’T AWFUL DOGMA BE SUCH A GOOD ALBUM NAME,” rather than settle on any definitive answer.

Besides, why insist on some vast distance between radical words and radical actions, anyway? Reading Villainy, I have the sense of a poet who is always working, observing, writing—a poet for whom “a different kind of march” where “we don’t steal anything / just space on the street—temporarily,” is just as much poetry, just as much protest as the “hot tub orgy / a few days later.” This is a poet who takes you on a walking tour of their city, pointing out the parts they still recognize, introducing you to their friends and influences along the way. Reading such a poet is an experience of extreme presence—so much so that when they say “hold my hand through the flash bangs / & i’ll hold yrs thru the flogging,” you might just offer in return a small promise to the pages in your hands.

The walking, the searching, the questioning continues in the final section of the book, “‘Poetry as Forces,’” a piece in conversation with artist and activist Cecilia Vicuña. The speaker asks, “how do we weaponize ourselves / how to weaponize the poem.” Here the conversational mode has been abandoned for fragments, short lines, blunt language, as if the speaker is ready to put down their pen and head back out into the streets. Reader, you may just have to join them.

Benjamin Grimes earned his MFA from Randolph College, where he worked on the lit mag Revolute. He writes poems and letters wherever he makes his home, which is currently the Berkshires. His poetry is forthcoming in the New Ohio Review.