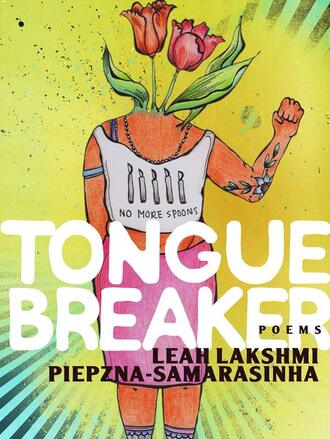

Tonguebreaker by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

Reviewed by C. Bain

… I’m your crip fairy godmother and I’m here to give you some important

information straight

This is not in any pamphlet the hospital will send you home with.

Its operating instructions. I mean to save your life

(from “Crip fairy godmother”)

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s 7th book and 3rd poetry collection, Tonguebreaker (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019), is a document of fierce survival, and a love letter to community. It is not abstract or delicate. It is not overly concerned with “craft.” It repeats itself. It creates identity through incantation. It insists on naming its own terms.

Though published before COVID-19 began, Piepzna-Samarasinha’s book speaks to how this pandemic is, among other things, an erasure of its precedents. In the face of what we are experiencing, collectively, now, there is endless rhetoric about how this is different, bigger, worse than anything else we have faced. The extent to which you believe our current situation is unique is the extent to which you have been able to live inside of the white, Western, fictional ideal of individuality. I’m referring to the idea that individuals are independent, and that individuals can create their circumstances. America’s bootstraps. This fiction of self-reliance ignores both the history of pandemic diseases (a year ago “the virus” meant something else) and the continual lack of any meaningful social support for those who are truly vulnerable. This pandemic has highlighted how keeping each other safe and caring for our own and others' well-being are inextricably linked—a lesson marginalized people, especially people with disabilities, have been trying to teach us for a long time. Suddenly, urgently, society at large is looking for the lessons that people pushed to the margins have known the whole time: that people are interdependent, that we rely on each other for our physical safety. Queers, people of color, the disabled (those in the “crip” community, to use Piepzna-Samarasinha’s reclaimed vocabulary) exist fundamentally in conflict with a nation and culture that want to deny them personhood. This conflict between the state and its marginal citizens does damage, but it also creates a fugitive network of mutual reliance, which becomes a source of support and nurturance independent of the state, outside of any formal control. Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s book is a generous invitation into this body of knowledge that they, a queer brown disabled femme, have accumulated via their survival.

In the poem “Birthday,” Piepzna-Samarasinha addresses their community of queer, disabled femme artists of color:

I want us to monster large together.

a perfect knife, broken and studded,

I love us, born broken blade,

Our love languages we half know celebrating each other’s birth

This is characteristic of the passionate, abundant, generous voice in Piepzna-Samarasinha’s collection. It is a language of care, a language that is direct and warm. One has the feeling, reading this work, that Piepzna-Samarasinha is world-building, creating a reality and a church from their loves, from the often-disposable lives of those dear to them. The speaker repeats "broken" twice, emphasizing the way a body's supposed "brokenness," according to our ableist culture, is also beautifully perfect and worthy of love. These lines, with their broken, ungrammatical syntax, embody the speaker's celebration of "each other's birth."

This book is a warm-blooded shift away from academia. It is a rebellion against respectability politics. The aesthetics of this book choose emotion over perfection, crafting a poetics that embodies "unruly" viscera. This book is a substantial, even packed, 140 pages. It begins with a prose-prologue about an imagined book of the same name, which Piepzna-Samarasinha was never ultimately allowed the resources or emotional space to write. The rest of the text is divided into several sections, many of them poems on different themes. Towards the end, there is a section of performance texts from Piepzna-Samarasinha’s time with Mangos With Chili, a QTPOC performance art collective they co-founded, active from 2008-2015. Here, again, Piepzna-Samarasinha speaks from before this pandemic but to the pandemic; the gentrification that was swallowing DIY performance spaces sure to be bolstered by the economic fallout of our current public health crisis. In one of these ritual texts, the voice over is:

surviving abuse bleeds into chronic illness bleeds into depression. I don’t

know when I got sick. When did I first need to sleep 17 hours a day and

awoke still unable to find words, go to the bathroom, finish a sentence?

When did my legs give out?

[…]

we make love in bed. we make love. we do. every part of me wants to make a

sarcastic joke about those words before, but what we do is make love and

that making love, sick crazy body to sick crazy body, that understands each

other so well, that making love is part of the healing of the world.

Again, I’m struck by the embodied knowledge Piepzna-Samarasinha speaks from here, and the paradoxical way that the reality of embodiment, and the connections that embodiment demands of us, are both our vulnerability and the only way we can survive. Piepzna-Samarasinha uses repetition (and reclamation) again, here, to take control of both the ableist language applied to them and to combat the censure against sexuality of people with disabilities.

There were moments that this collection did not speak to me, and that is frankly great. Piepzna-Samarasinha is writing for the survival of queer, disabled femmes of color, and as such they have every right to not be speaking to a white, transmasc reader. There were several moments that helped me, by giving me perspective or insight even if the text was intended more for in-group affirmation than out-group education. And there are moments that the poetry does its thing, luminous and levitating. Probably my favorite is a short poem called “Shark’s mouth:” :

My cunt is a cracked-open geode

spilling with a million bladed gems.

It’s hard to write a review of this because it is clear to me that the repetitions and ruptures, the prose-like and "unpoetic" craft elements in the collection are deliberate. I’m reminded of hearing Layli Long Soldier on a panel saying something like, "Don’t worry whether the work is beautiful, because your work is too important to get caught up in that." Tonguebreaker is a book that is very invested in identity; it is a book with a lot of didactic explication; it is a book that is relentlessly affirming, a book that champions community. These elements feel, at times, cumbersome (or alienating) to me as a reader, but their function is clearly important. The clear explanations throughout the book are part of its accessibility and urgency. The speaker does not want any confusion; they do not want anyone to be missed.

This reiterative quality, both as a set of themes that cycle through the work and as something that appears in introductory texts for the book and for individual pieces, bears some more examination. There is a clear generosity of intent, in Piepzna-Samarasinha’s clarity. But is it only a desire to be accessible and welcoming, or is there, underlying that, a desire not to be misconstrued? And am I, reading the book and feeling like the explanations and reiterations begin to deflate it a little, asking for a rejection of sense-making in favor of an aesthetic? Am I allowed to be frustrated by some of their formal choices, even though I can see that they are an altruist and a survivor, sharing their light?

Another function of the somewhat reiterative naming of identities and common experiences is that Piepzna-Samarasinha is locating themselves, and readers who can identify with them, in a lineage. Naming and renaming the book as a queer disabled femme of color work designates it as a site of power.

In one of the Mangos With Chili pieces dedicated to the memory of artist-activist HIV+ filmmaker Marlon Riggs, Piepzna-Samarasinha says:

It’s really simple. My vision of freedom?

My vision of freedom is one where we are not abandoned.

This is so clear, and so moving, and also presents a version of the paradox of the marginal artist. This is work that is about queerness, disability, being a femme of color living in a state that does not intend for you to survive. So, in a sense, wishing to thrive means wishing for the erasure of that marginal status. This book is self-definition, self-identification, as a self-and-world building project in the face of hostile forces. Without the hostile forces, the character of the work, the character of the lives and art practices of “marginal” people would change to an unrecognizable extent. This is work that is trying to erase its own usefulness. And what would be left, then? If the need of this kind of work is alleviated, what remains? It’s an existential question, but the moment that it comes into reality is far, far away. For now, the work stands under the umbrella “poetry” or “performance text” when what it truly offers is a manual for survival, for finding and loving others of your own kind. This type of survival, in a world this hostile, homogenizing, is itself an art.

information straight

This is not in any pamphlet the hospital will send you home with.

Its operating instructions. I mean to save your life

(from “Crip fairy godmother”)

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s 7th book and 3rd poetry collection, Tonguebreaker (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019), is a document of fierce survival, and a love letter to community. It is not abstract or delicate. It is not overly concerned with “craft.” It repeats itself. It creates identity through incantation. It insists on naming its own terms.

Though published before COVID-19 began, Piepzna-Samarasinha’s book speaks to how this pandemic is, among other things, an erasure of its precedents. In the face of what we are experiencing, collectively, now, there is endless rhetoric about how this is different, bigger, worse than anything else we have faced. The extent to which you believe our current situation is unique is the extent to which you have been able to live inside of the white, Western, fictional ideal of individuality. I’m referring to the idea that individuals are independent, and that individuals can create their circumstances. America’s bootstraps. This fiction of self-reliance ignores both the history of pandemic diseases (a year ago “the virus” meant something else) and the continual lack of any meaningful social support for those who are truly vulnerable. This pandemic has highlighted how keeping each other safe and caring for our own and others' well-being are inextricably linked—a lesson marginalized people, especially people with disabilities, have been trying to teach us for a long time. Suddenly, urgently, society at large is looking for the lessons that people pushed to the margins have known the whole time: that people are interdependent, that we rely on each other for our physical safety. Queers, people of color, the disabled (those in the “crip” community, to use Piepzna-Samarasinha’s reclaimed vocabulary) exist fundamentally in conflict with a nation and culture that want to deny them personhood. This conflict between the state and its marginal citizens does damage, but it also creates a fugitive network of mutual reliance, which becomes a source of support and nurturance independent of the state, outside of any formal control. Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s book is a generous invitation into this body of knowledge that they, a queer brown disabled femme, have accumulated via their survival.

In the poem “Birthday,” Piepzna-Samarasinha addresses their community of queer, disabled femme artists of color:

I want us to monster large together.

a perfect knife, broken and studded,

I love us, born broken blade,

Our love languages we half know celebrating each other’s birth

This is characteristic of the passionate, abundant, generous voice in Piepzna-Samarasinha’s collection. It is a language of care, a language that is direct and warm. One has the feeling, reading this work, that Piepzna-Samarasinha is world-building, creating a reality and a church from their loves, from the often-disposable lives of those dear to them. The speaker repeats "broken" twice, emphasizing the way a body's supposed "brokenness," according to our ableist culture, is also beautifully perfect and worthy of love. These lines, with their broken, ungrammatical syntax, embody the speaker's celebration of "each other's birth."

This book is a warm-blooded shift away from academia. It is a rebellion against respectability politics. The aesthetics of this book choose emotion over perfection, crafting a poetics that embodies "unruly" viscera. This book is a substantial, even packed, 140 pages. It begins with a prose-prologue about an imagined book of the same name, which Piepzna-Samarasinha was never ultimately allowed the resources or emotional space to write. The rest of the text is divided into several sections, many of them poems on different themes. Towards the end, there is a section of performance texts from Piepzna-Samarasinha’s time with Mangos With Chili, a QTPOC performance art collective they co-founded, active from 2008-2015. Here, again, Piepzna-Samarasinha speaks from before this pandemic but to the pandemic; the gentrification that was swallowing DIY performance spaces sure to be bolstered by the economic fallout of our current public health crisis. In one of these ritual texts, the voice over is:

surviving abuse bleeds into chronic illness bleeds into depression. I don’t

know when I got sick. When did I first need to sleep 17 hours a day and

awoke still unable to find words, go to the bathroom, finish a sentence?

When did my legs give out?

[…]

we make love in bed. we make love. we do. every part of me wants to make a

sarcastic joke about those words before, but what we do is make love and

that making love, sick crazy body to sick crazy body, that understands each

other so well, that making love is part of the healing of the world.

Again, I’m struck by the embodied knowledge Piepzna-Samarasinha speaks from here, and the paradoxical way that the reality of embodiment, and the connections that embodiment demands of us, are both our vulnerability and the only way we can survive. Piepzna-Samarasinha uses repetition (and reclamation) again, here, to take control of both the ableist language applied to them and to combat the censure against sexuality of people with disabilities.

There were moments that this collection did not speak to me, and that is frankly great. Piepzna-Samarasinha is writing for the survival of queer, disabled femmes of color, and as such they have every right to not be speaking to a white, transmasc reader. There were several moments that helped me, by giving me perspective or insight even if the text was intended more for in-group affirmation than out-group education. And there are moments that the poetry does its thing, luminous and levitating. Probably my favorite is a short poem called “Shark’s mouth:” :

My cunt is a cracked-open geode

spilling with a million bladed gems.

It’s hard to write a review of this because it is clear to me that the repetitions and ruptures, the prose-like and "unpoetic" craft elements in the collection are deliberate. I’m reminded of hearing Layli Long Soldier on a panel saying something like, "Don’t worry whether the work is beautiful, because your work is too important to get caught up in that." Tonguebreaker is a book that is very invested in identity; it is a book with a lot of didactic explication; it is a book that is relentlessly affirming, a book that champions community. These elements feel, at times, cumbersome (or alienating) to me as a reader, but their function is clearly important. The clear explanations throughout the book are part of its accessibility and urgency. The speaker does not want any confusion; they do not want anyone to be missed.

This reiterative quality, both as a set of themes that cycle through the work and as something that appears in introductory texts for the book and for individual pieces, bears some more examination. There is a clear generosity of intent, in Piepzna-Samarasinha’s clarity. But is it only a desire to be accessible and welcoming, or is there, underlying that, a desire not to be misconstrued? And am I, reading the book and feeling like the explanations and reiterations begin to deflate it a little, asking for a rejection of sense-making in favor of an aesthetic? Am I allowed to be frustrated by some of their formal choices, even though I can see that they are an altruist and a survivor, sharing their light?

Another function of the somewhat reiterative naming of identities and common experiences is that Piepzna-Samarasinha is locating themselves, and readers who can identify with them, in a lineage. Naming and renaming the book as a queer disabled femme of color work designates it as a site of power.

In one of the Mangos With Chili pieces dedicated to the memory of artist-activist HIV+ filmmaker Marlon Riggs, Piepzna-Samarasinha says:

It’s really simple. My vision of freedom?

My vision of freedom is one where we are not abandoned.

This is so clear, and so moving, and also presents a version of the paradox of the marginal artist. This is work that is about queerness, disability, being a femme of color living in a state that does not intend for you to survive. So, in a sense, wishing to thrive means wishing for the erasure of that marginal status. This book is self-definition, self-identification, as a self-and-world building project in the face of hostile forces. Without the hostile forces, the character of the work, the character of the lives and art practices of “marginal” people would change to an unrecognizable extent. This is work that is trying to erase its own usefulness. And what would be left, then? If the need of this kind of work is alleviated, what remains? It’s an existential question, but the moment that it comes into reality is far, far away. For now, the work stands under the umbrella “poetry” or “performance text” when what it truly offers is a manual for survival, for finding and loving others of your own kind. This type of survival, in a world this hostile, homogenizing, is itself an art.

C. Bain is a gender liminal artist based in Brooklyn. His book, Debridement, was a finalist for the Publishing Triangle awards. His writing is published in journals and anthologies such as BOAAT, them., Bedfellows Magazine, PANK, and elsewhere. His plays have been performed at Dixon Place, The Kraine, and The Tank in NYC. He is a performer, and has worked as an actor with several independent theater companies. He apprentices at Ugly Duckling Presse, and is a Lambda Literary fellow. He works extensively with trauma, embodiment, and sexuality, but he’d rather just dance with you. More at tiresiasprojekt.com