The Wet Hex by 신 선 영 Sun Yung Shin

Reviewed by francxs gufan nan

Content note for transnational adoption

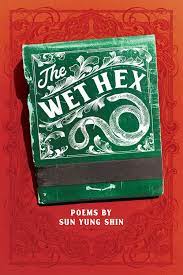

Sun Yung Shin's fourth book of poetry, The Wet Hex (Coffee House Press, 2022) conjures anew from the ashes of loss. Like the matchbook ("a carton of [...] quiet, time-release future fires," Shin writes in one poem) depicted on their cover, Shin's incandescent pages hold the means to destroy and reforge.

Composed of a first standalone poem, followed by five sections of between one to nine poems each, then an Appendix, The Wet Hex is at turns lucid—at others, elusive. The words of its mysterious title are never directly explained, appearing only once as a whole phrase in the poem, "An Orphan Receives Her Commercial DNA Test Results from Two Companies: An Abecedarian":

Ancestry laid upon a curse, a jinx

Blood, and another thing molten—reveries of my face, the facade behind my face

Called to account the countries, deviations of echolocations:

Dead—mine—dark-detained

Ever banked in an ethnographic afterlife.

Fell—deep sleep postponing my rewrite, rotate, mutate;

Genes to be circumnavigated by spit-polished explorers.

How is a child's globe a work of colonial conditioning?

In this condition, the wet hex in miniature

Jumps from gene sequence to succession.

By using the phrase "from [...] sequence to succession," Shin also invokes the etymology of "sequence": "in Church use, [...] a series of things following in a certain order, a succession." Just as DNA is a string of jumbled letters, that nonetheless dictate flesh and blood, by writing in an abecedarian—a form also dictated by a predetermined alphabetical order—Shin calls into question established order.

Similarly, in part of the epigraph, Shin unburies the etymology of the word "hex" in order to call into question what her reader may know:

“Hex” meaning “magic spell” was first recorded in 1909. Earlier it meant “witch,” see “hag,” meaning “repulsive old woman” probably from Old English: hægtes, hægtesse “witch, sorceress, enchantress, fury.” It is a word that has no male cognate.

By summoning forth the oft-forgotten connection between "hag" and "hex," Shin illumes the tethers between language, magic, and power, or lack thereof. The meaning of "hex" that their readers may be familiar with, Shin points out, overlays an older, gendered definition.

Likewise, the first standalone poem, "Translate This Body into Everything," serves as a divining rod for the rest of the collection, enervating to-be-repeated themes of Korean mythology, the alchemy of words, and the ineffable pain of the in-between:

How do we pronounce our skin in English,

turn our silences inside out like a fox-fur stole.

The Korean fox with nine tails is a demon,

always a woman, her heart thick with dreams

+

of human sacrifice, of the future of nature.

Korean girls who slept with the dictionary

so they would never be alone, so one day

they could give birth to bruises and poetry.

In Korean mythology, the kumiho 구미호 is a shapeshifter—and, like the witches at the root of "hex," gendered and unfairly maligned. Shin's lines move and shift via association as well: from "skin" as synecdoche for girls, to "fox-fur" as metaphor for self-soothing, to the demon-fox kumiho. Shin shows how a writer can enact powers of creation ("A poet can make the sun jealous," Shin later writes.) Letter by letter, word by word, symbol or meaning arranged and rearranged—these are the ways spelling can become spells, grammar become grimoire (a book of witchcraft, I learned from The Wet Hex).

Beyond ancient etymologies and mythologies, the poems of The Wet Hex draw from disparate sources, which Shin arranges alongside one another, skins, then builds upon. Shin's own government-issued passport, Wikipedia threads, a newspaper article, and especially classics of the western canon such as the Holy Bible, Moby Dick, Ovid's Metamorphoses all appear and are excerpted and transformed. In an interview last year, Shin shared, "I’ve always used recycling, borrowing from source texts as a way of having conversations with language and documents that have controlled our lives."

In the poem "Castaways in Paradise," Shin composes a contrapuntal of such master texts. On the left-side column, 26 lines are excerpted from Ovid's Metamorphoses: specifically, his version of the myth of Phaethon—son of the sun-god, who demands the reins to the sun-chariot as proof of his parentage—and of the unnamed-Callisto, transformed into a beast and unable to communicate. On the right-side column, Shin takes 23 lines—and plucks the poem's title—from Columbus: The Four Voyages 1492–1504. These columns are interrupted by photocopies of Shin's own personal passport from South Korea, before she was transnationally and transracially adopted by a white Catholic family in Chicago.

Thematically, the excerpts echo Shin's dedication for The Wet Hex, inscribed "to those cast away." In a 2017 interview with Vi Khi Nao, Shin posits, "I think my adoption documents are performing this writing of an identity, using language and paper—not images, not magic or ritual or religion, but state documents. [...] They perform magic, essentially, while pretending to be merely bureaucratic or governmental. They 'spell' who I am supposed to be."

At the center of The Wet Hex, in section 3, the speaker offers an alternative to the established order outside their pages, weaving their own version of mythology. In a single poem of 28 pages titled "Gaze _ Observatory _ Threshold: A 바리데기 Baridegi Reimagining"—almost every verso page emblazoned one of 13 with black-and-white drawings by Korean-Canadian artist Jinny Yu—Shin retells the story of Baridegi, a princess abandoned by her parents because of her gender. Yu's drawings are reminiscent of her 2020 series Hôte (French, meaning "host" and/or "guest"), in which she repeatedly sketched charcoal drawings of door motifs, while contemplating black-and-white or more shades-of-gray notions of "hosts" and "guest." Likewise, Shin's accompanying poetry repeats a motif of boxes throughout Baridegi's odyssey: from the jade box in which Baridegi is abandoned, to various thresholds across which she strides to save her dying father.

By sections 4 and 5, Shin further denatures the boundaries of poetic form. Whereas in early sections, most poems were right-aligned, in neat rows--by the end of The Wet Hex, Shin experiments with form and genre. Within the last six poems of section 4, Shin includes a palindrome poem, poems that are part 3- and 2-column contrapuntal, and a final poem with a running title (in which the poem's title turns out to be the first line of the poem). In the very last piece, Shin includes "an Appendix that is part poem, part lyric essay, and part translation dictionary"—in which her speaker confides, "I had to resort to a concise Wikipedia entry to see all the words for Korean family relationships," before reproducing the Korean Wikipedia entry on "Family and Relatives in English." Even when Shin's speaker lacks and must retrace a native language, the forms of Shin's collection speak loudly in the silence.

From castaways to spellcasters, the pages of the The Wet Hex shapeshift language, mythologies, and meaning. Drawing from sources across the western canon, as well as Shin's personal history, Shin creates a powerful new voice of her own.

Sun Yung Shin's fourth book of poetry, The Wet Hex (Coffee House Press, 2022) conjures anew from the ashes of loss. Like the matchbook ("a carton of [...] quiet, time-release future fires," Shin writes in one poem) depicted on their cover, Shin's incandescent pages hold the means to destroy and reforge.

Composed of a first standalone poem, followed by five sections of between one to nine poems each, then an Appendix, The Wet Hex is at turns lucid—at others, elusive. The words of its mysterious title are never directly explained, appearing only once as a whole phrase in the poem, "An Orphan Receives Her Commercial DNA Test Results from Two Companies: An Abecedarian":

Ancestry laid upon a curse, a jinx

Blood, and another thing molten—reveries of my face, the facade behind my face

Called to account the countries, deviations of echolocations:

Dead—mine—dark-detained

Ever banked in an ethnographic afterlife.

Fell—deep sleep postponing my rewrite, rotate, mutate;

Genes to be circumnavigated by spit-polished explorers.

How is a child's globe a work of colonial conditioning?

In this condition, the wet hex in miniature

Jumps from gene sequence to succession.

By using the phrase "from [...] sequence to succession," Shin also invokes the etymology of "sequence": "in Church use, [...] a series of things following in a certain order, a succession." Just as DNA is a string of jumbled letters, that nonetheless dictate flesh and blood, by writing in an abecedarian—a form also dictated by a predetermined alphabetical order—Shin calls into question established order.

Similarly, in part of the epigraph, Shin unburies the etymology of the word "hex" in order to call into question what her reader may know:

“Hex” meaning “magic spell” was first recorded in 1909. Earlier it meant “witch,” see “hag,” meaning “repulsive old woman” probably from Old English: hægtes, hægtesse “witch, sorceress, enchantress, fury.” It is a word that has no male cognate.

By summoning forth the oft-forgotten connection between "hag" and "hex," Shin illumes the tethers between language, magic, and power, or lack thereof. The meaning of "hex" that their readers may be familiar with, Shin points out, overlays an older, gendered definition.

Likewise, the first standalone poem, "Translate This Body into Everything," serves as a divining rod for the rest of the collection, enervating to-be-repeated themes of Korean mythology, the alchemy of words, and the ineffable pain of the in-between:

How do we pronounce our skin in English,

turn our silences inside out like a fox-fur stole.

The Korean fox with nine tails is a demon,

always a woman, her heart thick with dreams

+

of human sacrifice, of the future of nature.

Korean girls who slept with the dictionary

so they would never be alone, so one day

they could give birth to bruises and poetry.

In Korean mythology, the kumiho 구미호 is a shapeshifter—and, like the witches at the root of "hex," gendered and unfairly maligned. Shin's lines move and shift via association as well: from "skin" as synecdoche for girls, to "fox-fur" as metaphor for self-soothing, to the demon-fox kumiho. Shin shows how a writer can enact powers of creation ("A poet can make the sun jealous," Shin later writes.) Letter by letter, word by word, symbol or meaning arranged and rearranged—these are the ways spelling can become spells, grammar become grimoire (a book of witchcraft, I learned from The Wet Hex).

Beyond ancient etymologies and mythologies, the poems of The Wet Hex draw from disparate sources, which Shin arranges alongside one another, skins, then builds upon. Shin's own government-issued passport, Wikipedia threads, a newspaper article, and especially classics of the western canon such as the Holy Bible, Moby Dick, Ovid's Metamorphoses all appear and are excerpted and transformed. In an interview last year, Shin shared, "I’ve always used recycling, borrowing from source texts as a way of having conversations with language and documents that have controlled our lives."

In the poem "Castaways in Paradise," Shin composes a contrapuntal of such master texts. On the left-side column, 26 lines are excerpted from Ovid's Metamorphoses: specifically, his version of the myth of Phaethon—son of the sun-god, who demands the reins to the sun-chariot as proof of his parentage—and of the unnamed-Callisto, transformed into a beast and unable to communicate. On the right-side column, Shin takes 23 lines—and plucks the poem's title—from Columbus: The Four Voyages 1492–1504. These columns are interrupted by photocopies of Shin's own personal passport from South Korea, before she was transnationally and transracially adopted by a white Catholic family in Chicago.

Thematically, the excerpts echo Shin's dedication for The Wet Hex, inscribed "to those cast away." In a 2017 interview with Vi Khi Nao, Shin posits, "I think my adoption documents are performing this writing of an identity, using language and paper—not images, not magic or ritual or religion, but state documents. [...] They perform magic, essentially, while pretending to be merely bureaucratic or governmental. They 'spell' who I am supposed to be."

At the center of The Wet Hex, in section 3, the speaker offers an alternative to the established order outside their pages, weaving their own version of mythology. In a single poem of 28 pages titled "Gaze _ Observatory _ Threshold: A 바리데기 Baridegi Reimagining"—almost every verso page emblazoned one of 13 with black-and-white drawings by Korean-Canadian artist Jinny Yu—Shin retells the story of Baridegi, a princess abandoned by her parents because of her gender. Yu's drawings are reminiscent of her 2020 series Hôte (French, meaning "host" and/or "guest"), in which she repeatedly sketched charcoal drawings of door motifs, while contemplating black-and-white or more shades-of-gray notions of "hosts" and "guest." Likewise, Shin's accompanying poetry repeats a motif of boxes throughout Baridegi's odyssey: from the jade box in which Baridegi is abandoned, to various thresholds across which she strides to save her dying father.

By sections 4 and 5, Shin further denatures the boundaries of poetic form. Whereas in early sections, most poems were right-aligned, in neat rows--by the end of The Wet Hex, Shin experiments with form and genre. Within the last six poems of section 4, Shin includes a palindrome poem, poems that are part 3- and 2-column contrapuntal, and a final poem with a running title (in which the poem's title turns out to be the first line of the poem). In the very last piece, Shin includes "an Appendix that is part poem, part lyric essay, and part translation dictionary"—in which her speaker confides, "I had to resort to a concise Wikipedia entry to see all the words for Korean family relationships," before reproducing the Korean Wikipedia entry on "Family and Relatives in English." Even when Shin's speaker lacks and must retrace a native language, the forms of Shin's collection speak loudly in the silence.

From castaways to spellcasters, the pages of the The Wet Hex shapeshift language, mythologies, and meaning. Drawing from sources across the western canon, as well as Shin's personal history, Shin creates a powerful new voice of her own.

Frances Nan (francxs gufan nan) is almost 33. They have received fellowships from the Open Mouth Poetry Retreat, Brooklyn Poets, and The Watering Hole.