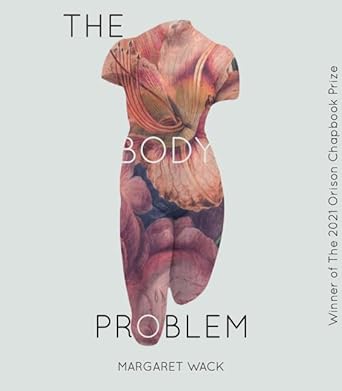

The Body Problem by Margaret Wack

Reviewed by Elizabeth Sylvia

Does anything prepare a person for the sensate glory of a failing world better than inhabiting the body of a girl, a wonder always moments from rot? Margaret Wack’s baroque and sumptuous first chapbook, The Body Problem, winner of the 2021 Orison Chapbook Prize, whispers, moans, and shrieks to answer that question. Ecological elegies bookend the chapbook, while its center brings concerns with love and ruin to the female body. This is a first collection from a daring and artful new poet that captures contemporary themes of Anthropocene decay and femme body discomfort with a bitten intensity of language. Ruby red with blood and juice, Margaret Wack’s collection mesmerizes.

The chapbook’s opening poem, “To the Future Citizens of Ruin and Promise,” lays out its overriding tension: “I, too, had an amber heart and a bruised / stomach. A shining wheat gold heart and a stomach grey with rotten / bounty.” Love and appetite, two wolves within us, sometimes collude and are often at odds. Throughout the book, appetite—sometimes dressed as desire—reflects humanity's greedy, two-fisted consumption of the world. This compulsion to pleasure can lead to abnegating guilt; love is the only possible solution to the wreck our destructive gluttony will leave behind.

The poem tells future citizens what and how current humans loved. We loved “strange music.… / animals…. / flowers,” and despite the coming ruin, the poem insists on our excesses:

…. You should know

that we, too, loved immoderately, like a struck match, like a rough sea,

like a gold bee in a lit field that knows the cold is coming.

The poems insist that the future, too, will be driven by love, despite human destruction of the planet. The speaker returns over and over to love’s necessity and inevitability. Love is a force that must be honored even when it drives destruction and lies, as she admits in “A Cruel Thing Within It,” beginning “I never killed a thing. That is a lie.” After listing the damage she has caused, the speaker justifies:

I know the world is cruel and I

Am a cruel thing within it. But still like a desperate and impotent god

I jealously guard the ones I love, I feed them the best bites, I comb

their dark hair.

Love is an active force, a gathering whose gold is touched by darkness, by the coming cold, or the breath that “could stop at any instant.”

The body is the site of love’s potential as it persists in its inexorable voyage to decay. The title poem posits that resisting the knowledge “your body will rot like a peony” might mean accepting commodification by the male gaze, becoming “a painting: flesh adored in wild color” rather than a living thing. Of course, this leads to another kind of breakage, requiring the capacity to be “confident and nearly shattered at the same time.” However, in Wack’s vision, the truest escape from destruction is away from a singular sense of the self and the body. “You must let go,” she writes, “This is not about god / it is about being swallowed.”

Poems dense with the physical body, with blood, bones and viscera reinforce the parallels between the self and the ruined world. Salvation comes from surrendering to rain that falls “not to clean …/ but to swallow” or to “the hungry mouths of confused / worshippers." The speaker imagines her clavicle cracked, her heart plucked out “like a sickly fruit.”

Such sacrificial imagery calls forth women of Greek mythology. In “Iphigenia,” the daughter Agamemnon sacrificed to appease Artemis’ wrath after he slaughtered one of her sacred stags appears. Iphegenia’s death may be the poem’s subject, but her father Agamemnon is its audience, the sinner who buys redemption with another’s blood:

…Somewhere a forest grove

a green that aches the skull like a split fruit. You kill the deer

You spill the blood you pay the price and the price is blood,

beloved, nothing else will do.

Despite the violence and rot which concern so many of these poems, The Body Problem is a book of living imagery, gothic in its combination of beauty and doom. The poems are color-saturated, teeming with animal visitors like the “cockroaches, indestructible, // resilient beyond the last possible mechanism of death.” The speaker transforms the cockroach’s persistence, often evoking a kind of horror, to nobility. In these poems, resilience is the greatest attribute to which the living can aspire.

We are “hellebore tongued, // leech kissed,” the speaker tells us in “Tips for Avoiding Tragedy,” an image that exemplifies the book’s mixture of blossom and blood. Over and over, Wack draws the reader’s eye to tiny wonders: “wild violets [that] line the road with open mouths," a sky with “the translucent skin of a saint.” This mesmerizing imagery, vampiric in its hunger, distinguishes The Body Problem as a distinctive addition to the new canon of ecopoetry.

The chapbook’s opening poem, “To the Future Citizens of Ruin and Promise,” lays out its overriding tension: “I, too, had an amber heart and a bruised / stomach. A shining wheat gold heart and a stomach grey with rotten / bounty.” Love and appetite, two wolves within us, sometimes collude and are often at odds. Throughout the book, appetite—sometimes dressed as desire—reflects humanity's greedy, two-fisted consumption of the world. This compulsion to pleasure can lead to abnegating guilt; love is the only possible solution to the wreck our destructive gluttony will leave behind.

The poem tells future citizens what and how current humans loved. We loved “strange music.… / animals…. / flowers,” and despite the coming ruin, the poem insists on our excesses:

…. You should know

that we, too, loved immoderately, like a struck match, like a rough sea,

like a gold bee in a lit field that knows the cold is coming.

The poems insist that the future, too, will be driven by love, despite human destruction of the planet. The speaker returns over and over to love’s necessity and inevitability. Love is a force that must be honored even when it drives destruction and lies, as she admits in “A Cruel Thing Within It,” beginning “I never killed a thing. That is a lie.” After listing the damage she has caused, the speaker justifies:

I know the world is cruel and I

Am a cruel thing within it. But still like a desperate and impotent god

I jealously guard the ones I love, I feed them the best bites, I comb

their dark hair.

Love is an active force, a gathering whose gold is touched by darkness, by the coming cold, or the breath that “could stop at any instant.”

The body is the site of love’s potential as it persists in its inexorable voyage to decay. The title poem posits that resisting the knowledge “your body will rot like a peony” might mean accepting commodification by the male gaze, becoming “a painting: flesh adored in wild color” rather than a living thing. Of course, this leads to another kind of breakage, requiring the capacity to be “confident and nearly shattered at the same time.” However, in Wack’s vision, the truest escape from destruction is away from a singular sense of the self and the body. “You must let go,” she writes, “This is not about god / it is about being swallowed.”

Poems dense with the physical body, with blood, bones and viscera reinforce the parallels between the self and the ruined world. Salvation comes from surrendering to rain that falls “not to clean …/ but to swallow” or to “the hungry mouths of confused / worshippers." The speaker imagines her clavicle cracked, her heart plucked out “like a sickly fruit.”

Such sacrificial imagery calls forth women of Greek mythology. In “Iphigenia,” the daughter Agamemnon sacrificed to appease Artemis’ wrath after he slaughtered one of her sacred stags appears. Iphegenia’s death may be the poem’s subject, but her father Agamemnon is its audience, the sinner who buys redemption with another’s blood:

…Somewhere a forest grove

a green that aches the skull like a split fruit. You kill the deer

You spill the blood you pay the price and the price is blood,

beloved, nothing else will do.

Despite the violence and rot which concern so many of these poems, The Body Problem is a book of living imagery, gothic in its combination of beauty and doom. The poems are color-saturated, teeming with animal visitors like the “cockroaches, indestructible, // resilient beyond the last possible mechanism of death.” The speaker transforms the cockroach’s persistence, often evoking a kind of horror, to nobility. In these poems, resilience is the greatest attribute to which the living can aspire.

We are “hellebore tongued, // leech kissed,” the speaker tells us in “Tips for Avoiding Tragedy,” an image that exemplifies the book’s mixture of blossom and blood. Over and over, Wack draws the reader’s eye to tiny wonders: “wild violets [that] line the road with open mouths," a sky with “the translucent skin of a saint.” This mesmerizing imagery, vampiric in its hunger, distinguishes The Body Problem as a distinctive addition to the new canon of ecopoetry.

Originally from Martha’s Vineyard, Elizabeth Sylvia (she/her) lives with her family in Massachusetts, where she teaches high school English. Since her first publication in 2019, Elizabeth has been featured in a range of magazines. None But Witches (2022), her first book, won the 2021 3 Mile Harbor Book Prize. A series of reflections on female experiences through Shakespeare’s women, it began with a New Year’s Resolution to read all of Shakespeare’s plays in a year. She is currently working on poems exploring Marie Antoinette and the end of the world.