"It all bleeds / into one story": The Daily Resistances of Special Education by Caroline M. Mar

Reviewed by francxs gufan nan

Content warning for institutional violence

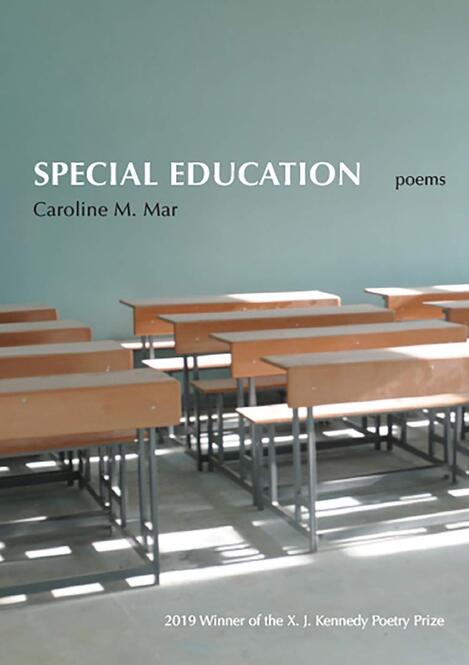

The U.S. education system has always been riddled with challenges, and for students that the mainstream education system wasn’t built to serve—English Language Learners, students of color, neurodivergent, physically disabled students, and/or students of size to name only a few—the problems are intensified. Caroline Mar’s Special Education (Texas Review Press, 2020) attempts to document these stories.

Dedicating the book to her students from her time teaching in San Francisco Unified School District, Mar shares many biographical similarities with her poems’ speaker. Both are mixed race white and Asian; teach and live in the San Francisco Bay Area; speak remnants of Cantonese inherited from their Chinatown-born paternal side of the family; have inherited wealth; and are married to white women named Sandy.

Special Education takes place in special education classrooms, the chaotic hallways between them, and the greater San Francisco Bay Area, where Mar’s speaker can leave school but remains haunted by the student turmoil that on most days she must barrel through, head down.

In 32 poems scaffolded over the course of 3 sections, Mar complicates the things she has been taught—or told—about teaching. Mar demonstrates expert knowledge of teachers’ best practices, while simultaneously problematizing them.

The standout pupil among these poems is the first, set on a verso page before the rest of the book. Titled “When You Someday Read This—,” the poem begins:

I took your story, held it to the light

like a glass I was checking for flecks

before putting it, tidy, on the shelf.

Directly addressing a “you”—perhaps the speaker’s students, perhaps her colleagues—the poem begins the book by asking for forgiveness: for “hiding you” in anonymity, “making your stories / one story,” and “breaking [the] glass” of their stories as well as any trust reneged by their telling. Mar’s speaker acknowledges and apologizes for the inevitable falsehoods that come from fictionalizing other people’s stories. From jump, Mar’s speaker problematizes the entire enterprise of her tome, atoning for speaking on behalf of “you,” and for crushing the glass of their stories and remelting them anew to suit her poems’ purposes.

If I imagine Mar’s book as a classroom, each poem a lesson, it’s incredible for the teacher-poet to begin by laying bare their shame. In traditional pedagogy, teachers are instructed to hold tight to their authority and limit the number of concessionary mistakes. But in Mar’s Special Education, harm is acknowledged and repented for.

Simultaneously, Mar pluralizes the harm-doing, laying responsibility at multiple doorsteps. The glass of these stories is broken “in my mouth, your mouth, / our mouths as we chewed.” Neither the reader nor speaker, audience nor actor, are blameless for consuming Mar’s speaker’s version of her students’ stories.

Nevertheless, the speaker-as-teacher answers for their own ignorance ex post facto, and offers for the storied to become storyteller. In the final lines of “When You Someday Read This—,” Mar’s speaker intones:

Forgive me: what I’ve forgotten,

what I wasn’t ready to say, what

I never knew. Inside your opening mouth

is a story, and I’m waiting--

for you to speak it, glass everywhere,

broken and ringing, that old

American sound.

Along with glass, there are ghosts. Among the many things the speaker knows about ghosts, one is that “ghosts can’t step over, that every door should / have a block,” as Mar writes in the poem “Ghost Language.” Here, Mar alludes to the ancient Chinese architectural tradition of a doorsill, or raised threshold. Built to keep in good fortune, to obstruct floodwater, rodents, or bad spirits, and to delineate a household from the outside world, the doorsill even serves a meditative function, to be crossed over—never tread on!—with presence of mind.

As fengshui dictates about doorways, the school culture where Mar’s speaker teaches dictates that what should stay at the door and outside the classroom is any detail about a teacher’s personal life. In the first poem of Mar’s first chapter, “Chinese Girl,” though her students hunger to know about her love life, and “what kinds of women [she’s] loved,” the speaker carefully self-edits what she shares about her past when in the classroom. The interracial tensions between the two sides of her family, and the ways her queerness is misread abroad and at home, such as by her future father-in-law—who turns hostile once he realizes the speaker is not merely a “sweet roommate” or “feminizing influence”—don’t get shared. Instead, she succinctly compresses these stories into “Happy marriage. Safely gay.”

Despite the pressures on Mar’s speaker to separate work from life, Mar’s poems in both the first and last section of Special Education defiantly explore the teacher-speaker’s multiple identities: teacher, granddaughter, wife, daughter(-in-law), citizen, and more. These poems defy the flattening and parsing of identity by statistics. The poems bookending Special Education gradually unveil the speaker’s multifaceted identity and past: the ghosts she carries with her that may remain unseen at work, blocked by the classroom door.

The poetic forms in Special Education establish their own cultural schema. “I teach the code’s switch,” Mar’s speaker declares, “the value of speaking both vernacular / and academic.” This, despite her mixed race body being read as a “white-ass” authority figure by her students, because “a teacher by any other name / is still fucking white-acting.”

Like any good teacher’s syllabus, scaffolded in its lessons like a long staircase, the poems of Special Education gradually intensify, step-by-step, section-by-section: “LANGUAGE LESSONS” contains mostly one- to three-page poems; “PRIMER,” two- to four-; and “EXAMINATION” crescendoes to include the book’s only two five-page poems.

The poetic forms also build like a rising staircase. In “LANGUAGE LESSONS,” Mar’s poems borrow words. One poem in this section, “Passing,” is a poem after A. Van Jordan that uses the dictionary, and its definitions, as form. Another poem in the first chapter, “Your Language, Your Face,” is a response to journalist Jose Antonio Vargas’s June 2011 essay in the New York Times coming out as undocumented. Mar’s poem is both an ekphrastic—addressing Ryan Pfluger’s portrait of Vargas, which accompanied Vargas’s essay—and an acrostic, since the first words of each line in Mar’s poem are the words from Vargas’s essay that framed Pfluger’s photograph. Like an English Language Learner struggling for expression, Mar’s poems in her first chapter build atop borrowed words.

In the second chapter of Special Education, “PRIMER,” Mar’s poems borrow voices. This chapter features collages and persona poems in different forms, such as a Golden Shovel and a contrapuntal. One section, “The Fix-up Strategies,” is a collage of early 2010s pop culture voices, from Kat Dahlia to the Annie E. Casey foundation website headlines. This series of poems draw their titles from literacy experts and education reformers. “Reread the Text,” a contrapuntal, compares a student’s unfiltered response to being disciplined alongside an apology in a more formal register. Last, in “EXAMINATION,” Mar’s poems echo and braid the speaker’s own voice, as in the gigan and ghazal forms. Together, these varied forms create a chorus of voices.

In a system that assumes her students are doomed, simply because they are separated into a Special Education classroom, there’s too much for teachers to do. Mar’s poems resist the scapegoating of teachers, chronicling the emotional push and pull of being responsible for students constantly coded as unreachable. Teaching, Mar’s poems insist, is not a vocation for the deficient: rather, teaching is a thousand tiny heartbreaks alongside thankless victories. “I showed my kids,” Mar’s speaker sorrows, “who tried to love / nothing.” Faced with willful ignorance even from other teachers—“no one wants a lecture on race / in this white city”—it’s all she can do to not wish for a ground-breaking earthquake of San Francisco proportions, then and there. Shattering glass, shattering stories.

The U.S. education system has always been riddled with challenges, and for students that the mainstream education system wasn’t built to serve—English Language Learners, students of color, neurodivergent, physically disabled students, and/or students of size to name only a few—the problems are intensified. Caroline Mar’s Special Education (Texas Review Press, 2020) attempts to document these stories.

Dedicating the book to her students from her time teaching in San Francisco Unified School District, Mar shares many biographical similarities with her poems’ speaker. Both are mixed race white and Asian; teach and live in the San Francisco Bay Area; speak remnants of Cantonese inherited from their Chinatown-born paternal side of the family; have inherited wealth; and are married to white women named Sandy.

Special Education takes place in special education classrooms, the chaotic hallways between them, and the greater San Francisco Bay Area, where Mar’s speaker can leave school but remains haunted by the student turmoil that on most days she must barrel through, head down.

In 32 poems scaffolded over the course of 3 sections, Mar complicates the things she has been taught—or told—about teaching. Mar demonstrates expert knowledge of teachers’ best practices, while simultaneously problematizing them.

The standout pupil among these poems is the first, set on a verso page before the rest of the book. Titled “When You Someday Read This—,” the poem begins:

I took your story, held it to the light

like a glass I was checking for flecks

before putting it, tidy, on the shelf.

Directly addressing a “you”—perhaps the speaker’s students, perhaps her colleagues—the poem begins the book by asking for forgiveness: for “hiding you” in anonymity, “making your stories / one story,” and “breaking [the] glass” of their stories as well as any trust reneged by their telling. Mar’s speaker acknowledges and apologizes for the inevitable falsehoods that come from fictionalizing other people’s stories. From jump, Mar’s speaker problematizes the entire enterprise of her tome, atoning for speaking on behalf of “you,” and for crushing the glass of their stories and remelting them anew to suit her poems’ purposes.

If I imagine Mar’s book as a classroom, each poem a lesson, it’s incredible for the teacher-poet to begin by laying bare their shame. In traditional pedagogy, teachers are instructed to hold tight to their authority and limit the number of concessionary mistakes. But in Mar’s Special Education, harm is acknowledged and repented for.

Simultaneously, Mar pluralizes the harm-doing, laying responsibility at multiple doorsteps. The glass of these stories is broken “in my mouth, your mouth, / our mouths as we chewed.” Neither the reader nor speaker, audience nor actor, are blameless for consuming Mar’s speaker’s version of her students’ stories.

Nevertheless, the speaker-as-teacher answers for their own ignorance ex post facto, and offers for the storied to become storyteller. In the final lines of “When You Someday Read This—,” Mar’s speaker intones:

Forgive me: what I’ve forgotten,

what I wasn’t ready to say, what

I never knew. Inside your opening mouth

is a story, and I’m waiting--

for you to speak it, glass everywhere,

broken and ringing, that old

American sound.

Along with glass, there are ghosts. Among the many things the speaker knows about ghosts, one is that “ghosts can’t step over, that every door should / have a block,” as Mar writes in the poem “Ghost Language.” Here, Mar alludes to the ancient Chinese architectural tradition of a doorsill, or raised threshold. Built to keep in good fortune, to obstruct floodwater, rodents, or bad spirits, and to delineate a household from the outside world, the doorsill even serves a meditative function, to be crossed over—never tread on!—with presence of mind.

As fengshui dictates about doorways, the school culture where Mar’s speaker teaches dictates that what should stay at the door and outside the classroom is any detail about a teacher’s personal life. In the first poem of Mar’s first chapter, “Chinese Girl,” though her students hunger to know about her love life, and “what kinds of women [she’s] loved,” the speaker carefully self-edits what she shares about her past when in the classroom. The interracial tensions between the two sides of her family, and the ways her queerness is misread abroad and at home, such as by her future father-in-law—who turns hostile once he realizes the speaker is not merely a “sweet roommate” or “feminizing influence”—don’t get shared. Instead, she succinctly compresses these stories into “Happy marriage. Safely gay.”

Despite the pressures on Mar’s speaker to separate work from life, Mar’s poems in both the first and last section of Special Education defiantly explore the teacher-speaker’s multiple identities: teacher, granddaughter, wife, daughter(-in-law), citizen, and more. These poems defy the flattening and parsing of identity by statistics. The poems bookending Special Education gradually unveil the speaker’s multifaceted identity and past: the ghosts she carries with her that may remain unseen at work, blocked by the classroom door.

The poetic forms in Special Education establish their own cultural schema. “I teach the code’s switch,” Mar’s speaker declares, “the value of speaking both vernacular / and academic.” This, despite her mixed race body being read as a “white-ass” authority figure by her students, because “a teacher by any other name / is still fucking white-acting.”

Like any good teacher’s syllabus, scaffolded in its lessons like a long staircase, the poems of Special Education gradually intensify, step-by-step, section-by-section: “LANGUAGE LESSONS” contains mostly one- to three-page poems; “PRIMER,” two- to four-; and “EXAMINATION” crescendoes to include the book’s only two five-page poems.

The poetic forms also build like a rising staircase. In “LANGUAGE LESSONS,” Mar’s poems borrow words. One poem in this section, “Passing,” is a poem after A. Van Jordan that uses the dictionary, and its definitions, as form. Another poem in the first chapter, “Your Language, Your Face,” is a response to journalist Jose Antonio Vargas’s June 2011 essay in the New York Times coming out as undocumented. Mar’s poem is both an ekphrastic—addressing Ryan Pfluger’s portrait of Vargas, which accompanied Vargas’s essay—and an acrostic, since the first words of each line in Mar’s poem are the words from Vargas’s essay that framed Pfluger’s photograph. Like an English Language Learner struggling for expression, Mar’s poems in her first chapter build atop borrowed words.

In the second chapter of Special Education, “PRIMER,” Mar’s poems borrow voices. This chapter features collages and persona poems in different forms, such as a Golden Shovel and a contrapuntal. One section, “The Fix-up Strategies,” is a collage of early 2010s pop culture voices, from Kat Dahlia to the Annie E. Casey foundation website headlines. This series of poems draw their titles from literacy experts and education reformers. “Reread the Text,” a contrapuntal, compares a student’s unfiltered response to being disciplined alongside an apology in a more formal register. Last, in “EXAMINATION,” Mar’s poems echo and braid the speaker’s own voice, as in the gigan and ghazal forms. Together, these varied forms create a chorus of voices.

In a system that assumes her students are doomed, simply because they are separated into a Special Education classroom, there’s too much for teachers to do. Mar’s poems resist the scapegoating of teachers, chronicling the emotional push and pull of being responsible for students constantly coded as unreachable. Teaching, Mar’s poems insist, is not a vocation for the deficient: rather, teaching is a thousand tiny heartbreaks alongside thankless victories. “I showed my kids,” Mar’s speaker sorrows, “who tried to love / nothing.” Faced with willful ignorance even from other teachers—“no one wants a lecture on race / in this white city”—it’s all she can do to not wish for a ground-breaking earthquake of San Francisco proportions, then and there. Shattering glass, shattering stories.

Frances Nan (francxs gufan nan) is 31 and an emerging poet. Their “balding haibun” won the inaugural Pigeon Pages NYC 2020 Poetry Contest, selected by Ada Limón, and was recently nominated for a Pushcart Prize. She is a reader for Frontier Poetry and has received fellowships from the Open Mouth Poetry Retreat, Brooklyn Poets, and The Watering Hole.