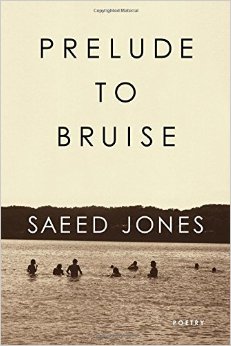

Prelude to Bruise by Saeed Jones

A Review by Corrina Bain, Book Reviewer

I feel a little guilty that I uncomplicatedly love a book as complicated as Prelude to Bruise, Saeed Jones’ anticipated debut poetry collection. I’ve been aware of Jones’ work in journals, readings, from his Sibling Rivalry Press-published chapbook, and I’ve been chomping at the bit for his full-length. Of course, that means I could have been disappointed. But I wasn’t. Take these lines from “Closet of Red”:

Up to my ankles in petals, the hanged gowns close it,

mother multiplied, more—there’s always more

corseted ghosts, red-silk bodies crowd my mouth…

What am I supposed to do with this as a reviewer? “BOOYAKASHA! Nailed it!” is not really sufficient as a review. He nails it, though. Jones walks back and forth on a bridge between the ordinary, daily world and more opulent imaginings. Much of the book revolves around Boy, who flickers in and out of the earlier part of the book in a series of lyrical, half-dreamed poems full of threat and transformation. (Let me just titillate you with some titles: “Boy Found Inside A Wolf,” “Boy in a Stolen Evening Gown,” “Boy at Threshold.”) Then Boy returns in the penultimate section of the book moving through a realistic, concrete landscape. Here is another strength of Jones’ writing: even when he is drawing up a clear, autobiographical-feeling narrative, it is not easy or didactic. Boy’s position as a protagonist does not feel theatrical or forced.

Jones articulates the longing inside of everything. In bible stories (from Isaac After Mount Moriah: “Dirty-haired boy, my rascal, my sacrifice. Never / an easy dream. I watch him wrestle my shadow.”) In kudzu (“soil recoils from my hooked kisses/…/All I’ve ever wanted / was to kiss crevices, pry them open”). In hate crime (an astonishing poem called “Jasper 1998” and a found poem made of texts about the laws forbidding people of color to travel at night come to mind most readily), and the sex that exists alongside the promise of that violence.

If I do have a more complicated response to this book, it is to the challenge it raises for me as a writer. What is the relationship between art and desire, how desire moves through the world? Is it “responsible” to tell these concurrent, juxtaposed stories: cultural subjugation, homophobic and racist violence, and the warp and rupture of the family, to tell those stories alongside the sexual subjugation which (at least to me, it seems,) is so desired? And if it is not responsible, if it aggrandizes a re-traumatizing, a self-degradation, then what does the writer do when truth and responsibility are at odds? Jones seems to say, you tell the truth. It is a powerful and gorgeous message, but not a comfortable one.

What these poems show us is the necessity of owning that longing, the refusal to let the wounds the world has laid upon us turn inward, into our shame, our silence. To show the world the face that the world has made:

I survived on mouthfuls of hyacinth.

My hunger did not apologize.

Stamens licked clean, pollinated

throat; Beauty was what I choked on.

When the men with cruel tongues

worked me, each grunt gnashed

between my teeth…

Or from “Beheaded Kingdom”:

With his one good knife, a door is cut to where the spine waits: patient,

then flaring. All my lights turned on. A scream is loosed,

grey silk sound pulled out by hooks, black before the filaments.

Quiet, he begs, rakish doctor. Then a hand goes in.

Here is the crux of the book, for me, the thing which makes me sigh and turn back through it over again and read it aloud to my boobookitty who doesn’t even like poems all that much. The silencing quality of fear, the thing that takes us out of ourselves politically and undermines the possibility of a clear American discussion of race or sex, is exposed here as a continuous field which is both inside and outside the self. Or in English, the political is personal. The subjugation to your inner gods, the pain inside the erotic, the way that fear and desire mirror each other, because you cannot want something that is entirely unlike what has badly hurt you, this is what I see in Jones’ work. It is not a political commentary or a psychological study, when I could have tumbled into either. It is art, and as such it can’t be argued with.

Up to my ankles in petals, the hanged gowns close it,

mother multiplied, more—there’s always more

corseted ghosts, red-silk bodies crowd my mouth…

What am I supposed to do with this as a reviewer? “BOOYAKASHA! Nailed it!” is not really sufficient as a review. He nails it, though. Jones walks back and forth on a bridge between the ordinary, daily world and more opulent imaginings. Much of the book revolves around Boy, who flickers in and out of the earlier part of the book in a series of lyrical, half-dreamed poems full of threat and transformation. (Let me just titillate you with some titles: “Boy Found Inside A Wolf,” “Boy in a Stolen Evening Gown,” “Boy at Threshold.”) Then Boy returns in the penultimate section of the book moving through a realistic, concrete landscape. Here is another strength of Jones’ writing: even when he is drawing up a clear, autobiographical-feeling narrative, it is not easy or didactic. Boy’s position as a protagonist does not feel theatrical or forced.

Jones articulates the longing inside of everything. In bible stories (from Isaac After Mount Moriah: “Dirty-haired boy, my rascal, my sacrifice. Never / an easy dream. I watch him wrestle my shadow.”) In kudzu (“soil recoils from my hooked kisses/…/All I’ve ever wanted / was to kiss crevices, pry them open”). In hate crime (an astonishing poem called “Jasper 1998” and a found poem made of texts about the laws forbidding people of color to travel at night come to mind most readily), and the sex that exists alongside the promise of that violence.

If I do have a more complicated response to this book, it is to the challenge it raises for me as a writer. What is the relationship between art and desire, how desire moves through the world? Is it “responsible” to tell these concurrent, juxtaposed stories: cultural subjugation, homophobic and racist violence, and the warp and rupture of the family, to tell those stories alongside the sexual subjugation which (at least to me, it seems,) is so desired? And if it is not responsible, if it aggrandizes a re-traumatizing, a self-degradation, then what does the writer do when truth and responsibility are at odds? Jones seems to say, you tell the truth. It is a powerful and gorgeous message, but not a comfortable one.

What these poems show us is the necessity of owning that longing, the refusal to let the wounds the world has laid upon us turn inward, into our shame, our silence. To show the world the face that the world has made:

I survived on mouthfuls of hyacinth.

My hunger did not apologize.

Stamens licked clean, pollinated

throat; Beauty was what I choked on.

When the men with cruel tongues

worked me, each grunt gnashed

between my teeth…

Or from “Beheaded Kingdom”:

With his one good knife, a door is cut to where the spine waits: patient,

then flaring. All my lights turned on. A scream is loosed,

grey silk sound pulled out by hooks, black before the filaments.

Quiet, he begs, rakish doctor. Then a hand goes in.

Here is the crux of the book, for me, the thing which makes me sigh and turn back through it over again and read it aloud to my boobookitty who doesn’t even like poems all that much. The silencing quality of fear, the thing that takes us out of ourselves politically and undermines the possibility of a clear American discussion of race or sex, is exposed here as a continuous field which is both inside and outside the self. Or in English, the political is personal. The subjugation to your inner gods, the pain inside the erotic, the way that fear and desire mirror each other, because you cannot want something that is entirely unlike what has badly hurt you, this is what I see in Jones’ work. It is not a political commentary or a psychological study, when I could have tumbled into either. It is art, and as such it can’t be argued with.