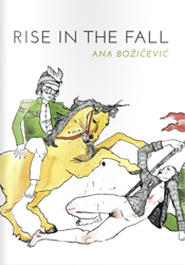

Rise in the Fall by Ana Božičević

A Review by Lindsay King-Miller, Book Reviewer

Rise in the Fall, the second full-length poetry collection by Croatian-born New York poet Ana Božičević, was impossible for me to read at a measured pace. I meant to dole it out over several sittings but ended up devouring it whole, one marathon session sprawled out across my bed. Božičević's first book, Stars of the Night Commute, is one I constantly, compulsively reread, filled with underlining and dog-eared marginalia. Her second collection, the delivery of which I anticipated for weeks, lived up to all my expectations.

Rise in the Fall, more than Božičević's first book, grapples directly with the question of what poetry is and what it can do. These questions are not abstractions; Božičević is concerned with the real-world implications of being a poet, of trying to find beauty or profundity in the displacement and trauma of contemporary life. “What's war?” she writes in “War on a Lunchbreak.” “Eternal countrylessness. / Lady poets writing about cock, / not thinking about gender.” Here, poetry is both the ultimate tangent – a disruption, an afterthought – and the only possible way to translate what is essential. Desire and need, violence and theory, overlap, as later in the poem when Božičević writes,

I know there's war all around me,

and inside there's war: who died, who cheated,

when will she look at me like that,

what language is this, I hope no-one breaks in and rapes us.

I never see sunlight.

Having taken classes with Ana Božičević and attended her readings, it's impossible to hear her work without the lilt of her accent. She writes with a remarkable lightness, with the ability to pivot a line on its heel and never lose the accrued momentum. She writes with a bit of a smirk, a wry self-awareness that neither obscures nor negates the depth of her earnestness. In the middle of “About Nietzsche,” the collection's first poem, Božičević interrupts herself to say,

This is the whitest shit

I've ever written. Truth is, Osama bin Laden

was killed today, two women were shot

in that raid, and yet again

I can't escape this feeling of living in a world of men

whose intricate games

I'm to jeer and cheer, but they leave my head

blank like

a foggy morning.

Božičević writes about queerness, women, war, migration, the experiences that make a person foreign, that make a person a stranger. In “Intervals of Please,” she writes:

Through the war I fondled a picture

of a girl, right in front of that

girl.

Her handshake felt

just like a

handjob.

But when she

stepped on the

mine

her body looked

not cute. Her

leg

soaring through the air

was not cute.

Later in the same poem, she writes, “This poem is meant to be admonishment. / So why am I trying to squeeze beauty into / admonishment.” Božičević's poems flinch toward beauty, impulsively adorning even what is grotesque. The poetic instinct battles with the conscience, as countless other writers have experienced; what sets Božičević apart, however, is that she transcribes the entire push-and-pull, not simply its result.

The poems in Rise in the Fall overflow with awkwardly beautiful self-awareness, with a consciousness of the gap between what the writer wants to say and what poetry can really contain:

I wanted

to write something called:

Portrait of the Immigrant as Your Little Pony.

About how all over America

I travel to sing my song that there is no song

About my bombed body as the site of abandonment,

& I'd be the critical darling, and they'd say She did it –

but nothing

no song came

not anti-song, just nothing.

This preoccupation with writing as a never-ending process could easily become distracting, even gimmicky, if it weren't so obviously heartfelt and handled with such elegance.

These poems are full of bravery and second-guessing, lust and hesitation, self-righteousness and self-doubt. The pressure to confess is complicated by the instinct toward obscurity. Something is always hidden in the gesture of revealing, and yet the desire to tell the truth propagates itself:

So much of my life

I've held out against the forces of green. If

I dive in, I can't stop—

I have to go into the father I abandoned, lick

every individual stone street, write down each

letter.

Here, desire is always present; it's inextricable from the migrant experience, the poet experience, the experience of war. Still, neither wanting nor wanting to be wanted are simple. “Don't moon me with your downtown / provinces—I want to be the kind of monster you don't want to fuck—” she writes in “Casual Elegy for Luka Skračić.” The narrative voice's refusal to be legibly “sexy” or “desirable,” to present a coherent narrative of sexuality, is the source of much of the work's strength.

All the strands are connected through the permanent state of upheaval, the constant shifting of connections and disconnections, that Božičević channels so deftly: “Revolution is everywhere / like god, its nemesis. That's an old quarrel. Parts of the sky / fall down to earth, face down in a field,” she writes in “The Fall of Luci.” This collection is revolutionary in the sense that it is constantly turning, constantly transforming, looking at its subjects from different angles. “I know there's something wrong with this poem,” she writes, “but I'm done trying to clean up any of it.” These poems are constantly comparing themselves to some platonic ideal of poetry and falling artfully, intentionally, short. Their (perceived, perhaps imaginary) shortcomings are their scaffolding, the structure they wear on the outside. This is poetry with visible seams, messy and unapologetic.