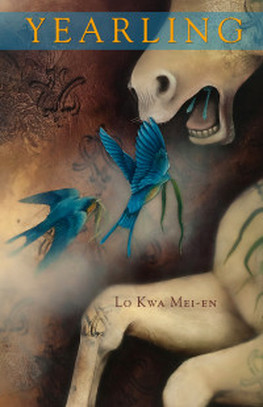

Yearling by Lo Kwa Mei-En (Alice James, 2015)

Reviewed by Irène Mathieu, Book Reviewer

In Yearling by Lo Kwa Mei-En (Alice James, 2015), her poems pray for “the meek to inherit something gorgeous,” and then offer it to us in the form of a dizzying, red world that defies borders. This book unabashedly creates a new vocabulary by using words in surprising ways (“to the great by then / ruth that canaried through the ruthless bodies / of water”). She often uses deft enjambment to metamorphose images (for instance, “the strange, red swell of a barn / swallow’s belly” in the poem “hic sunt dracones”). Mei-En wields language in Yearling like a pickaxe. It’s a deconstruction. These poetics pick apart the world as we know it, gear by gear, place the whole messy heap in front of us, and then build something strange and new before our eyes.

The book is divided into three sections, each with a distinct emotional timbre. The first section is full of defiance, violence, fear, temper, and bloody hell. It’s the language of rebellion as elaborated in “Poem the Size of a Wing,” borne from being a “thing of beauty / waiting to be comprehended, as you do not wait / for me,” so that “[i]n sleep, I do not dream without anger / stroking at the soft pit of my knee.” The second section deals with the aftermath of rage, when “the low tides unbutton themselves about our feet / in plain sight of all” in “Prodigal Animals.” As the title of this poem suggests, it’s in this section of the book that Mei-En’s poetry strips the speakers down to their primordial state:

The blueprint, to no one, that caught

the blow of the wind and bolted off with

what was promised me – a little loss, and

at some point, levitation.

(from “Left to Those I Love”)

The final section is imbued with hope for our reconciliation: “[i]t was never a question of one side / over the other. The body that has something to say / knows better than that. / Lights everything on fire with one hand / and tends coals with the other” (from “The Body That Has Something to Say”). In “Canon with Wolves in the Water” the speaker asserts that “[t]he world may end in fire,” but in the previous poem (“Pinnocchia on Fire”) it’s heat that bestows rebirth – “temperature and light, so hot, so real, I come alive.”

Much of Yearling grapples with the a/morality of nature and Christianity. Mei-En writes about psalms and gardens of Eden but they do not sit comfortably in these poems – after all, in the poem “A Girl Thief’s Illustrated Primer” we find “first-felony Eve in the red telephone booth / outside the garden, a battle coal / dialing herself back into the war.” Large bodies of water appear and reappear, making the speaker(s) seem adrift, as if we are privy to a private process of navigation in a nameless ocean. There are geese eggs and Thoreauvian beetles, chokecherry and a whole menagerie of animal ghosts hanging out inside a banyan tree.

But neither the pat prescriptiveness of religion nor the brutality of nature seem an adequate moral compass for these poems’ speaker(s), as if their inadequacy is the reason for deconstructing the world as we know it. Religion – or human-made systems of morality that sometimes seem based on judgmental, gendered dichotomies for Yearling’s speaker(s) – is insufficient to answer the book’s fundamental question: “how to eat this planet up / to get us to the next”? The character Pinocchia, who appears in several poems to wrestle with these dichotomies, is “the realest thing for days,” yet in this world she is still but a wooden nautical figurehead, as described in “Pinnocchia, we loved you enough.” Yearling is not here to tell us how to make what we love more real; it’s creating a new, realer world in patchwork fashion:

Let the low tides unbutton themselves about our feet

in plain sight of all. There’s a word for where they go

meaning years to an animal with a softer spine and inner

ear. Meaning a minor world, emergent, its language mine,

still scarred by echoes and oil.

(from “Prodigal Animals”)

Perhaps it is unsurprising, then, that there is something disorienting about this book. To find my footing in the incredible world Mei-En creates, I found myself reading these poems aloud out of necessity, as if hearing them conjured up their new world in a more visceral way (I often got lost trying to read them silently); something new must be summoned, announced. If “[t]he world is another cage I cannot map,” then Yearling has mapped a world without cage bars, and what could be more disorienting than that? As another poem asserts, “I must wander. Be brave. Rise / elsewhere.” These poems do nothing if not wander and rise bravely, creating new territories as they go. By reconfiguring reality as we know it, Yearling offers a glimpse into the new world we might invent.

The book is divided into three sections, each with a distinct emotional timbre. The first section is full of defiance, violence, fear, temper, and bloody hell. It’s the language of rebellion as elaborated in “Poem the Size of a Wing,” borne from being a “thing of beauty / waiting to be comprehended, as you do not wait / for me,” so that “[i]n sleep, I do not dream without anger / stroking at the soft pit of my knee.” The second section deals with the aftermath of rage, when “the low tides unbutton themselves about our feet / in plain sight of all” in “Prodigal Animals.” As the title of this poem suggests, it’s in this section of the book that Mei-En’s poetry strips the speakers down to their primordial state:

The blueprint, to no one, that caught

the blow of the wind and bolted off with

what was promised me – a little loss, and

at some point, levitation.

(from “Left to Those I Love”)

The final section is imbued with hope for our reconciliation: “[i]t was never a question of one side / over the other. The body that has something to say / knows better than that. / Lights everything on fire with one hand / and tends coals with the other” (from “The Body That Has Something to Say”). In “Canon with Wolves in the Water” the speaker asserts that “[t]he world may end in fire,” but in the previous poem (“Pinnocchia on Fire”) it’s heat that bestows rebirth – “temperature and light, so hot, so real, I come alive.”

Much of Yearling grapples with the a/morality of nature and Christianity. Mei-En writes about psalms and gardens of Eden but they do not sit comfortably in these poems – after all, in the poem “A Girl Thief’s Illustrated Primer” we find “first-felony Eve in the red telephone booth / outside the garden, a battle coal / dialing herself back into the war.” Large bodies of water appear and reappear, making the speaker(s) seem adrift, as if we are privy to a private process of navigation in a nameless ocean. There are geese eggs and Thoreauvian beetles, chokecherry and a whole menagerie of animal ghosts hanging out inside a banyan tree.

But neither the pat prescriptiveness of religion nor the brutality of nature seem an adequate moral compass for these poems’ speaker(s), as if their inadequacy is the reason for deconstructing the world as we know it. Religion – or human-made systems of morality that sometimes seem based on judgmental, gendered dichotomies for Yearling’s speaker(s) – is insufficient to answer the book’s fundamental question: “how to eat this planet up / to get us to the next”? The character Pinocchia, who appears in several poems to wrestle with these dichotomies, is “the realest thing for days,” yet in this world she is still but a wooden nautical figurehead, as described in “Pinnocchia, we loved you enough.” Yearling is not here to tell us how to make what we love more real; it’s creating a new, realer world in patchwork fashion:

Let the low tides unbutton themselves about our feet

in plain sight of all. There’s a word for where they go

meaning years to an animal with a softer spine and inner

ear. Meaning a minor world, emergent, its language mine,

still scarred by echoes and oil.

(from “Prodigal Animals”)

Perhaps it is unsurprising, then, that there is something disorienting about this book. To find my footing in the incredible world Mei-En creates, I found myself reading these poems aloud out of necessity, as if hearing them conjured up their new world in a more visceral way (I often got lost trying to read them silently); something new must be summoned, announced. If “[t]he world is another cage I cannot map,” then Yearling has mapped a world without cage bars, and what could be more disorienting than that? As another poem asserts, “I must wander. Be brave. Rise / elsewhere.” These poems do nothing if not wander and rise bravely, creating new territories as they go. By reconfiguring reality as we know it, Yearling offers a glimpse into the new world we might invent.