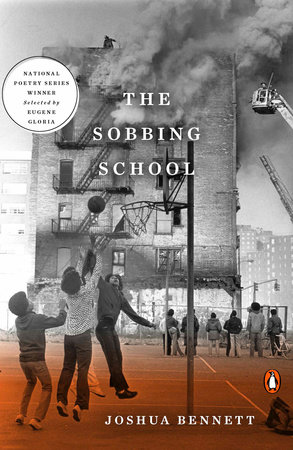

The Sobbing School by Joshua Bennett (Penguin, 2016)

Reviewed by C. Bain, Book Reviewer

It’s hard to sit down and review a book of poetry in End Times. It’s hard to do anything, sure, but it’s hard to focus on beautified language, sitting, as we are, in a political climate where “I know words, I have the best words,” is part of the discourse. I am grateful that, of all the books I could have in front of me, I have Joshua Bennett’s debut collection of poems, The Sobbing School (Penguin, 2016). This book is even more aware and more perturbed by End Times than I am. In “On Extinction,” in an uncharacteristically plainspoken stanza, Bennett writes:

The woman across the table from me is scared

to raise her son, fears he will be killed

by police, says this outright, over soup,

expecting nothing.

We have arrived here as a society: at a place where the police do not represent safety, but a bloodied, unwieldy appendage of power. We are in an atmosphere where a level of aggression and terror is simultaneously unignorable and invisible, depending on where you stand. For the people who are aware of this ongoing and accelerating threat, it is so pervasive that it almost has to be normalized, it has to become banal, in order to allow for the possibility of living your life at all. The Sobbing School is a document of this strange emotional position: urgency without panic. The tension between a desire for clarity and the knowledge that clarity will not necessarily be a balm.

The book title is taken from a Zora Neale Hurston quote, used as an epigraph to the work: “I do not belong to the sobbing school of Negrohood who hold that nature somehow has given them a lowdown dirty deal and whose feelings are all hurt about it… No, I do not weep at the world—I am too busy sharpening my oyster knife.” So where does this book place itself? Is it the Sobbing School itself? Or part of Hurston’s protest against such sobbing? Is it possible that it is both? In these poems, I find a sobbing quality that has to do with the elevation of language. It is almost an oppressive beauty, emerging not despite the violence but from within it, and also somehow obscuring it:

Then the blond man

on the A train last month, his broken nose turning

each fist into a bolt of red silk.

Or in "The Order of Things," which follows violence from the speaker’s character from the present into childhood, then back into his father’s life:

Christina and her friends threw me

up against the fence, held me

like a portrait in a museum boasting

free admission for students under the age

of ten. The chain-link made latticework

of my unremarkable back.

The violence, and the body caught up in it, seem heavy, remote, ornamented, unlike (at least in my experience) the hot, languageless shock of violence. I wonder about the task of translating life (which includes violence) into art, and whether that is possible, whether something will always be lost, and so it makes sense to lose it in the service of beauty. Arguments against this beautification exist (I am thinking of Mary Karr’s essay "Against Decoration" and of feminist writers like Sexton of Acker, or myself for that matter.) Reading this book, and looking at the level of craft and the intersection of that craft with Black American experience, I am struck by the thought that it is a kind of entitlement, also, to hold up my narrative, unadorned, and expect it to hold a reader’s attention. Isn’t that a kind of privilege, to expect whatever I say to be fascinating, simply because I think of it as true? Certainly Hemingway was Hemingway largely because he was white (shouted out in the collection, also, in a piece titled “Whenever Hemingway Hums N_____). If we are going to fail to make art that actually conveys our experience (and we are, that failure is intrinsic) then maybe it is better to fail beautifully than to fail in the pursuit of some idea of “accuracy,” which we can never really attain.

There are also moments when the speaker of the poems looks at their intelligence, their elevated language, and sees how that alienates the very subject of the work. In “Fresh” (one of a few excellent, questing poems about the speaker’s relationship with their father), the piece culminates in the speaker’s father describing his diction:

as if it were on display,

floating in a bulletproof box:

The way all those words

come out of your head, man.

It’s amazing. It’s like a book

or something.

There are also many times when that same intelligence is used to hold up Black American history, to trouble the sobbing school with portraits of fortitude or joy, in treatments of Henry “Box” Brown, Richard Wright and others. One thread which runs through the work is a series of poems called “In Defense.” And how layered, how multifaceted, is simply the phrase “in defense” in the mouth of a Black American at this moment in our history? My favorite poem in the collection is “In Defense of Passing,” which offers not a literal treatment of passing or passability, but an imagined world where personal, wearable cloaking devices render the wearer whatever race they wish. I won’t tell you the ending, but it’s sad. Bennett explores defense more literally in another poem, “Home Force: Presumption of Death,” which is an erasure of Florida’s Stand Your Ground legislation:

person is assumed to have a self or body.

…

personhood does nor apply

if the son against whom force is used

has no lawful owner or title to protect.

violence against the child is wise.

…

it is necessary

to prevent the body, harm

him, sing get over it.

Let me end where the book ends, where I began this review. End Times. Helplessness. The longing for action and the fear that no action will connect. Bennett ends the collection with “Preface to a Twenty Volume Regicide Note,” which both honors Baraka and illuminates the need to turn the violence away from the self. Maybe that is what is valuable about the beautification of violence – that it makes the violence external. It gives it a weight and a name. That naming, that language of our experience, is the tool which Alice Walker talks about as the only one that can never be wrested from us This poem arrives at a directness and urgency which only emerges a few times in the book, and therefore sings out, exceptional and clear. Bennett writes:

Lately I’ve become accustomed to the way

each newly dead face flashes like a crushed fire

-work across the screen. The red mass

of each name.

…

On a good day, I honor the war

by calling it war.

The woman across the table from me is scared

to raise her son, fears he will be killed

by police, says this outright, over soup,

expecting nothing.

We have arrived here as a society: at a place where the police do not represent safety, but a bloodied, unwieldy appendage of power. We are in an atmosphere where a level of aggression and terror is simultaneously unignorable and invisible, depending on where you stand. For the people who are aware of this ongoing and accelerating threat, it is so pervasive that it almost has to be normalized, it has to become banal, in order to allow for the possibility of living your life at all. The Sobbing School is a document of this strange emotional position: urgency without panic. The tension between a desire for clarity and the knowledge that clarity will not necessarily be a balm.

The book title is taken from a Zora Neale Hurston quote, used as an epigraph to the work: “I do not belong to the sobbing school of Negrohood who hold that nature somehow has given them a lowdown dirty deal and whose feelings are all hurt about it… No, I do not weep at the world—I am too busy sharpening my oyster knife.” So where does this book place itself? Is it the Sobbing School itself? Or part of Hurston’s protest against such sobbing? Is it possible that it is both? In these poems, I find a sobbing quality that has to do with the elevation of language. It is almost an oppressive beauty, emerging not despite the violence but from within it, and also somehow obscuring it:

Then the blond man

on the A train last month, his broken nose turning

each fist into a bolt of red silk.

Or in "The Order of Things," which follows violence from the speaker’s character from the present into childhood, then back into his father’s life:

Christina and her friends threw me

up against the fence, held me

like a portrait in a museum boasting

free admission for students under the age

of ten. The chain-link made latticework

of my unremarkable back.

The violence, and the body caught up in it, seem heavy, remote, ornamented, unlike (at least in my experience) the hot, languageless shock of violence. I wonder about the task of translating life (which includes violence) into art, and whether that is possible, whether something will always be lost, and so it makes sense to lose it in the service of beauty. Arguments against this beautification exist (I am thinking of Mary Karr’s essay "Against Decoration" and of feminist writers like Sexton of Acker, or myself for that matter.) Reading this book, and looking at the level of craft and the intersection of that craft with Black American experience, I am struck by the thought that it is a kind of entitlement, also, to hold up my narrative, unadorned, and expect it to hold a reader’s attention. Isn’t that a kind of privilege, to expect whatever I say to be fascinating, simply because I think of it as true? Certainly Hemingway was Hemingway largely because he was white (shouted out in the collection, also, in a piece titled “Whenever Hemingway Hums N_____). If we are going to fail to make art that actually conveys our experience (and we are, that failure is intrinsic) then maybe it is better to fail beautifully than to fail in the pursuit of some idea of “accuracy,” which we can never really attain.

There are also moments when the speaker of the poems looks at their intelligence, their elevated language, and sees how that alienates the very subject of the work. In “Fresh” (one of a few excellent, questing poems about the speaker’s relationship with their father), the piece culminates in the speaker’s father describing his diction:

as if it were on display,

floating in a bulletproof box:

The way all those words

come out of your head, man.

It’s amazing. It’s like a book

or something.

There are also many times when that same intelligence is used to hold up Black American history, to trouble the sobbing school with portraits of fortitude or joy, in treatments of Henry “Box” Brown, Richard Wright and others. One thread which runs through the work is a series of poems called “In Defense.” And how layered, how multifaceted, is simply the phrase “in defense” in the mouth of a Black American at this moment in our history? My favorite poem in the collection is “In Defense of Passing,” which offers not a literal treatment of passing or passability, but an imagined world where personal, wearable cloaking devices render the wearer whatever race they wish. I won’t tell you the ending, but it’s sad. Bennett explores defense more literally in another poem, “Home Force: Presumption of Death,” which is an erasure of Florida’s Stand Your Ground legislation:

person is assumed to have a self or body.

…

personhood does nor apply

if the son against whom force is used

has no lawful owner or title to protect.

violence against the child is wise.

…

it is necessary

to prevent the body, harm

him, sing get over it.

Let me end where the book ends, where I began this review. End Times. Helplessness. The longing for action and the fear that no action will connect. Bennett ends the collection with “Preface to a Twenty Volume Regicide Note,” which both honors Baraka and illuminates the need to turn the violence away from the self. Maybe that is what is valuable about the beautification of violence – that it makes the violence external. It gives it a weight and a name. That naming, that language of our experience, is the tool which Alice Walker talks about as the only one that can never be wrested from us This poem arrives at a directness and urgency which only emerges a few times in the book, and therefore sings out, exceptional and clear. Bennett writes:

Lately I’ve become accustomed to the way

each newly dead face flashes like a crushed fire

-work across the screen. The red mass

of each name.

…

On a good day, I honor the war

by calling it war.