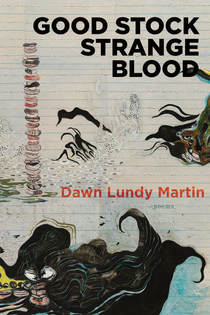

Good Stock Strange Blood by Dawn Lundy Martin (Coffee House Press, 2017)

Reviewed by C. Bain

How often have you felt like you were dreaming, lately? How many times have you gotten a news alert or scrolled through social media or had someone tell you something about our cultural/political moment, and thought to yourself “that just can’t be right.” Police protecting Nazi rallies? The literal president of the United States baiting a world leader by tweeting that he is short and fat? A family values senatorial candidate with an open history of sexually pursuing children, who still has the support of his party? I’m not saying that I am shocked; all of it is consistent with where we have been headed as a culture. Yet, it is also blatant to the point that it strains belief. This is the world, and it is also the world of Dawn Lundy Martin’s fourth book of poetry, Good Stock Strange Blood (Coffee House Press 2017). Martin is working deftly between worlds, amid “a failure of images.” She works across poetry and prose, transcendental and mundane. For example, in a poem later in the book called “– untethered from happenings rooted to temporality—” she begins with:

The I is made of many arches and windows. Enter this structure, the

Entrances to the many houses of god.

And yet, each morning a fireheart grief coming out of sleep…

Then towards the poem’s conclusion, we come to:

—We have stolen madness from the white people.

—An Asian white man will call us a crazy bitch in a text.

But we have long done been free. Coffee is brought to our bedside on a

silver tray. We are unrepresentable. We sip into the griefmouth.

This facility, leaping from abstraction into the contemporary and political into the immediately personal, is rewarding even as it is disorienting. She leaves us with a text that is, like a dream, boundariless, haunting, and difficult to hold in the grip of the mind.

Parts of this book were concieved as a libretto for Good Stock On The Dimension Floor, which we learn in an introduction written as a lyric-essay-interview with footnotes. Martin wrote this opera in collaboration with the HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN? global artists collective. It was produced as a film, initially screened at the Whitney but withdrawn in protest of the museum’s racist and sexist curatorial practices. The opera is also, we learn in this same introduction, in relationship with Sarah, the protagonist of Adrienne Kennedy’s Funnyhouse of a Negro, an important theatre piece of the Black Arts movement. Funnyhouse occurs largely inside of Sarah’s mind. The introductory essay/interview (including the query “Why exhale after the inhale? The breathing is the mantra. Could the trauma be keeping us alive?”) leads into the book which changes form throughout. Bolded “titles” become opening lines. Interruptions/ fragments of italicized text, neither integrated nor completely separate from their surround, intersperse the more discrete pieces. The content and form work together to reinforce the dream-state, like the book is a modern codex, a grappling with threads of information which seem disparate but echo each other.

There is a sense of loss in the revision, maybe born of transposing parts of the project from libretto into a book of poems. And perhaps this is my background in performance poetry, with its (excessively) clear narrative quality and identity politics, but I kept longing for more solidity, more clarity. The moments that felt closest to that were, funnily, dream sequences within the text; the speaker describing a dream of hiding and burying a body in a house gave me a sense of the immediacy, the anxiety of hiding. I love the dream as a window and extension of the speaker’s experience, because as a white reader, as a person who was socialized with a tacit, polite, liberal New England white supremacy, it is easier for me to think of racism as abstract, an injustice happening in a system, as opposed to daily, individual, intimate experiences of people of color. I’m saying, for many years, because of where I was located culturally, I thought of racism as unjust but not emotional, not personal. So, it is generous for Martin to let the reader see the juncture between her lived experience and the unconscious. I also believe it is important and worthwhile for writers, sometimes, to keep the reader out; “to love incessantly despite the reader’s inability to extract anything at all from the remnant,” as Martin herself describes in a section called “Counterband [tangentials].” I think that there is power, as a writer who holds any marginalized identity, in refusing to explain yourself, in refusing to make your work and its relevance transparent. A Black, queer voice is relevant even if it avoids a direct address of any identity politic. It is relevant because it has not been extinguished.

Nor should I imply that Martin is avoiding race in this book. Race exists, again, from the moment of introduction, when the speaker says that this book comes from “the summer of Sandra Bland and then the summer of Freddie Gray.” And how miserable it is that invoking death, here, is invoking race. This, too, becomes part of the dream-haunting overarching the book, that there is this spectre of death, of historical trauma carried in a body that trauma is also being acted out upon.

While I keep talking about dream-states, about the book’s floating, edgeless quality, I should say this is also a fiercely embodied work. The speaker of these poems says that she can stay in bed, depressed, “so hungry I’m distorted.” She mentions her vagina/cunt. She says “—I could tell you how to fall— from one sphere to another. You see, you fall through the gut and when you arrive at the next place, you squeeze a rough hard knee.” In fact, it feels possible that while Funnyhouse was set largely in the mind of the protagonist, this book is floating around the speaker’s body. Sometimes the poems are face-like, presentable, ready to address the world, and at other moments the voice feels very private, so private that the poem does not release its secret to the reader at all.

This returns me to the tension between dissociation-trance-dream-removal and connection to the world. Again, it keeps washing over me, the world and my interfaces with it, increasingly dreamlike. In the world, it is harder and harder to parse the racist rhetoric, the acts of violence and state sanctioned violence, the trauma narratives, entertainment, politics—they no longer feel discrete. In this way, Good Stock Strange Blood is a perfect book for our moment. It does not pretend to offer a solution, only to the possibility that what is happening is somehow even larger than it feels. “To imagine something other is to escape the known world” Martin writes, “No death. But, instead, the door.” It is hard to stay connected with the time we are in without dissolving into polemic, which is ultimately dishonest. Martin’s book is very movingly successful in that it is deeply felt, deeply feeling, without ever constructing a simple political paradigm or telling the reader how to feel. The book ends, opaque, militant, bittersweet, with a call to action that contains not glamour or hype, a limited, realist hope:

Leave wreckage by the roadside.

Burn all decayed tissue.

Tightrope from which we emerge.

The I is made of many arches and windows. Enter this structure, the

Entrances to the many houses of god.

And yet, each morning a fireheart grief coming out of sleep…

Then towards the poem’s conclusion, we come to:

—We have stolen madness from the white people.

—An Asian white man will call us a crazy bitch in a text.

But we have long done been free. Coffee is brought to our bedside on a

silver tray. We are unrepresentable. We sip into the griefmouth.

This facility, leaping from abstraction into the contemporary and political into the immediately personal, is rewarding even as it is disorienting. She leaves us with a text that is, like a dream, boundariless, haunting, and difficult to hold in the grip of the mind.

Parts of this book were concieved as a libretto for Good Stock On The Dimension Floor, which we learn in an introduction written as a lyric-essay-interview with footnotes. Martin wrote this opera in collaboration with the HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN? global artists collective. It was produced as a film, initially screened at the Whitney but withdrawn in protest of the museum’s racist and sexist curatorial practices. The opera is also, we learn in this same introduction, in relationship with Sarah, the protagonist of Adrienne Kennedy’s Funnyhouse of a Negro, an important theatre piece of the Black Arts movement. Funnyhouse occurs largely inside of Sarah’s mind. The introductory essay/interview (including the query “Why exhale after the inhale? The breathing is the mantra. Could the trauma be keeping us alive?”) leads into the book which changes form throughout. Bolded “titles” become opening lines. Interruptions/ fragments of italicized text, neither integrated nor completely separate from their surround, intersperse the more discrete pieces. The content and form work together to reinforce the dream-state, like the book is a modern codex, a grappling with threads of information which seem disparate but echo each other.

There is a sense of loss in the revision, maybe born of transposing parts of the project from libretto into a book of poems. And perhaps this is my background in performance poetry, with its (excessively) clear narrative quality and identity politics, but I kept longing for more solidity, more clarity. The moments that felt closest to that were, funnily, dream sequences within the text; the speaker describing a dream of hiding and burying a body in a house gave me a sense of the immediacy, the anxiety of hiding. I love the dream as a window and extension of the speaker’s experience, because as a white reader, as a person who was socialized with a tacit, polite, liberal New England white supremacy, it is easier for me to think of racism as abstract, an injustice happening in a system, as opposed to daily, individual, intimate experiences of people of color. I’m saying, for many years, because of where I was located culturally, I thought of racism as unjust but not emotional, not personal. So, it is generous for Martin to let the reader see the juncture between her lived experience and the unconscious. I also believe it is important and worthwhile for writers, sometimes, to keep the reader out; “to love incessantly despite the reader’s inability to extract anything at all from the remnant,” as Martin herself describes in a section called “Counterband [tangentials].” I think that there is power, as a writer who holds any marginalized identity, in refusing to explain yourself, in refusing to make your work and its relevance transparent. A Black, queer voice is relevant even if it avoids a direct address of any identity politic. It is relevant because it has not been extinguished.

Nor should I imply that Martin is avoiding race in this book. Race exists, again, from the moment of introduction, when the speaker says that this book comes from “the summer of Sandra Bland and then the summer of Freddie Gray.” And how miserable it is that invoking death, here, is invoking race. This, too, becomes part of the dream-haunting overarching the book, that there is this spectre of death, of historical trauma carried in a body that trauma is also being acted out upon.

While I keep talking about dream-states, about the book’s floating, edgeless quality, I should say this is also a fiercely embodied work. The speaker of these poems says that she can stay in bed, depressed, “so hungry I’m distorted.” She mentions her vagina/cunt. She says “—I could tell you how to fall— from one sphere to another. You see, you fall through the gut and when you arrive at the next place, you squeeze a rough hard knee.” In fact, it feels possible that while Funnyhouse was set largely in the mind of the protagonist, this book is floating around the speaker’s body. Sometimes the poems are face-like, presentable, ready to address the world, and at other moments the voice feels very private, so private that the poem does not release its secret to the reader at all.

This returns me to the tension between dissociation-trance-dream-removal and connection to the world. Again, it keeps washing over me, the world and my interfaces with it, increasingly dreamlike. In the world, it is harder and harder to parse the racist rhetoric, the acts of violence and state sanctioned violence, the trauma narratives, entertainment, politics—they no longer feel discrete. In this way, Good Stock Strange Blood is a perfect book for our moment. It does not pretend to offer a solution, only to the possibility that what is happening is somehow even larger than it feels. “To imagine something other is to escape the known world” Martin writes, “No death. But, instead, the door.” It is hard to stay connected with the time we are in without dissolving into polemic, which is ultimately dishonest. Martin’s book is very movingly successful in that it is deeply felt, deeply feeling, without ever constructing a simple political paradigm or telling the reader how to feel. The book ends, opaque, militant, bittersweet, with a call to action that contains not glamour or hype, a limited, realist hope:

Leave wreckage by the roadside.

Burn all decayed tissue.

Tightrope from which we emerge.