Exiles of Eden by Ladan Osman

Reviewed by C. Bain

Ladan Osman’s second book, Exiles of Eden (Coffee House Press, 2019) brings the reader immediately into a detailed, uncomfortable beauty:

How can I fail outside and inside our home? I decay in our half-life.

How can I fail with my body? How do I stay alone in this half life?

I started a ghazal about my hope’s stress fracture.

So begins the first poem of the collection, and just as quickly, the reader encounters a voice of unique self-awareness and intelligence, locating the body and its failures, and the responsibility for those failures, starkly in the center of a rich and uneasy world. With that intelligence and vision comes a troubled heart. Within the span of the first poem, and echoing throughout the collection, we witness a grimly permeable boundary, between the self, the beloved, the nation, and the physical world.

One of the challenges of writing poetry, or thinking poetically, in this cultural moment is that so much is happening at once, and so much information is constantly available. I think many writers respond to this with a deliberate superficiality, a kind of self-defense against the barrage of demands on our attention, emotions, time. Osman does not give into this jaded escapism. She is writing in the late anthropecene here-and-now and refusing to surrender to anesthesia. In “Practice With Yearning Theorem: Loci,” for example, the speaker looks at Google map images of Somalia (Osman’s country of birth). There are literal images from Google maps interspersed with memories of an ex-military ex-husband. Again, the violence lands both across the expanse of the globe, the expanse of memory, and within the speaker’s body:

A catastrophic separation: First, space between my joints. Then

Parts reduced to currents and less than that, stretching apart.

I don’t have physical language for it. If you report this form of pain

they call it depression, or other sickness…

…

My ex-husband would visit Iraq online, retrace the route he followed.

This didn’t seem legal… My lack of sympathy was a kernel between

us. I hate uniforms, family reunion T-shirts. People all dressed the

same, standing in a park.

…

In Somali, jab means break, fragment but also defeat or loss…

I sunder in a different language…

The speaker of these poems allows in the violence perpetrated by their husband in Iraq, the violence of othering and dissociation that is the casual attendant of removed technological observation of suffering, and splices it into her own hearbreak, her own sundering.

These poems are, as I mentioned, self-aware, acutely aware of the stage on which they unfold both in the geopolitical world and within the emotional reality of the speaker. Yet, they are not self-conscious, in a way that poets who are very aware of language sometimes lapse into. Osman’s deliberate and unusual language choices, rather than creating a distance or prettiness, manage to engender a directness that leaves the reader between refreshment and shock. In “Inventory: Shrinkage” she writes:

I can’t tell the difference between

incense dust,

a rabbit pellet,

Is it food or waste?

And the moon.

It’s all ash.

Moments like this make me feel like I am witnessing a space alien or one of Shakespeare’s weird sisters being forced to walk around and do their business in the regular world. The events and objects in these poems are recognizable, but they have been through a sea change in the poet’s vision.

Another through line in the collection, and another way Osman is completing a time-sensitive and often botched aesthetic task, is the presence of technology in the world of the book. There is a presence, a cold pressure on the poems, perhaps not as overt or organized as surveillance, but nonetheless exerted by a technological god. The Google map images I mentioned earlier in “Yearning Theorem: Loci” are one instance of this. Another example comes in a piece titled “Autocorrect” which begins:

“Lynch whenever works best for you.”

I mean, “Lunch.” It’s too late.

This insertion of the word lynch drags us into the speaker’s memory, viewing documentation of lynchings in history textbooks, the speaker both witness and object within the image of the lynching. This specificity, rather than creating the limitation of a time-stamp, seems to open the poems into the particular intellectual challenge of being a poet in this moment. What does it mean to make deliberate, discrete pieces of art out of language in an environment when language, un-synthesized, un-curated, saturates most of our waking moments? The balance Osman has struck, acknowledging the pressures and impacts of the environment and nonetheless emerging with a distinct, certain voice, moved me repeatedly over the course of this book.

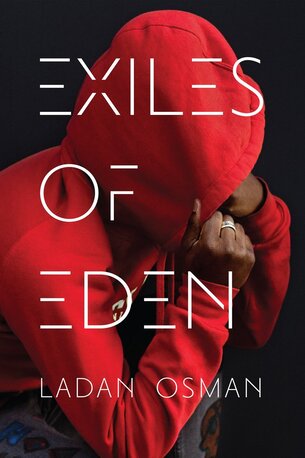

Images, literal visual images, are also central to this book, which incorporates Osman’s other artistic practice as a photographer. Some of the images are clearly related to the poems they accompany, as in “Inventory: Shrinkage,” which refers to a housefly telling the speaker which direction to pray in, with photographs of a fly crawling on a manuscript. There are other images, like “Rebound Rapt” or the “Double Consciousness” series, one of which serves as the book’s cover, which somehow mythologize their subjects (young people of color) without staging or altering them in the least. This quality of presenting images which are at once realistic and candid and also classical in scope is a striking extension of the aesthetic of Osman’s poetic voice. In the “Double Consciousness” images, the classical echo of a cauled, shrouded figure is resurrected in a Black boy in a hoodie, both an everyday figure and a nexus of mystery. Using the title “Double Consciousness,” Osman is also contextualizing her work and herself, referring to the term W. E. B. Du Bois used to describe the split awareness inherent in Black American identity: the knowledge of one’s humanity pitted against the refusal of one’s nation to admit one’s humanness. Osman is never speaking from a simple identity politic, but the awareness of these poems feels vast, pained, and multiple in a way which resonates with this idea.

This mythic quality is something which Osman leans into in some specific poems as well, generally in a biblical cast, with poems called “Sympathy for Eve” and “Sympathy for Satan,” and perhaps it is this integration, this employment of a larger frame, which allows this book to be dark, specific, and exacting without lapsing into hopelessness. Despite the stark sadness and displacement of many of the poems, this is not a book of despair. This is another real victory, another successful navigation of a difficult intellectual area. These poems find a hope, a fighting spirit, which does not bely or negate the other, more challenging emotional content of the work, for example in the closing lines of “Devotional with Misheard Lyrics:”

I’m simple only in this: I need two armed hugs.

I sing in the street, small blasphemy

in the diaphragm’s dome:

My lover’s not human. Amen.

At the shrine of your light,

like a dog, like a dog.

The joy or hope to be found here is not effusive, but it is authentic and unforced, and that allows me to take it seriously. As I started by talking about the beginning of the book, let me end by talking about the end: Osman closes with a long poem, a call to survival and sisterhood titled “Refusing Eurydice” which ends with a litany:

We left the serpents underfoot in peace

and refuse their bites.

We refuse death by discourse.

We refuse death by exile.

We refuse death by falling,

and we refuse death in depressions.

We are looking for a better myth.

We’ve only been looking since Eve.