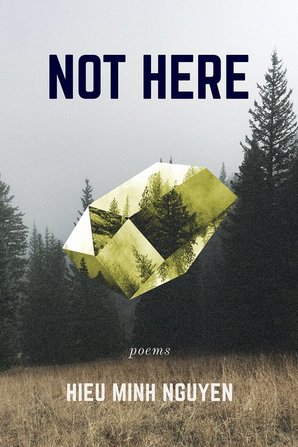

Not Here by Hieu Minh Nguyen (Coffee House Press, 2018)

Reviewed by C. Bain, Staff Book Reviewer

Recently I’ve been thinking a lot about white desire. Or rather, I’ve been thinking about how my desire, which is white, is not benign. White desire bears the weight and ammunition of history, whether we invite them or not. When a white person is attracted (or ‘fascinated’ or ‘enchanted’ or whatever, I mean, I am a poet unfortunately), to someone who is already tasked with symbolizing the Other, then that desire can potentially replicate their other experiences of being made into objects. So it was timely and rewarding for me, to review Hieu Minh Nguyen’s Not Here (Coffee House Press, 2018.) Although white desire is certainly not the only subject, these poems, with gut-punching emotion and hard-edged beauty, offer maps of the desire-line through that territory. For example, in “Ode to the Pubic Hair Stuck in My Throat,” where Nguyen uses the humorous title and relatable moment as a setup for a serious and beautiful chain of images, we are given the lines:

remind me

what it’s like to speak

without

a white man

flickering in my throat

Or, later, “Mercy,” a heartbreaking accounting of the emotional violence inflicted on the speaker by white sex partners, opens with:

Once, while lying in his bed

a man asked me to quiet

his dog by speaking to it

in Vietnamese, said

well, she is your people

And while the white men in these poems easily do enough to implicate themselves as villains, the poems do not concern themselves with accusing the men. That is, I didn’t feel lectured or antagonized. There is an unavoidable political undercurrent, but the poem isn’t politicized, it’s not polemical, or making an argument that extends from these moments. Rather, the moments themselves are illuminated, and then the speaker turns again towards himself, offering us more questions. I feel a little like I’m apologizing or equivocating about the political weight of this work, and that’s not what I want to do. Maybe I mean that there are poems, (I’m thinking of work by Solmaz Sharif and Layli Long Soldier,) where the poet takes the reader’s hand and escorts them into the politics of the moment. Then there are other poems, like most of Not Here, that arrive at a political truth through a private door. The way the poem rests in our America, our political moment, is for the reader to construct. These windows into the desire, or complicity, of the person faced with white desire are heartbreaking and haunting and all but unique, in my experience as a reader.

But I do not want to lock Not Here into this facet of its subject matter, despite how important and generous it was for me to find these poems. Not Here, as the title suggests, also deals with place, sometimes a high school cafeteria, sometimes an arcing, primordial location where either ancestors or history-stripped boy machines assemble. Nguyen also writes with vitality and grace about the body, about trauma/memory/time, and about family. It is a testament to the unifying passion of the work that poems with this breadth of subject feel like they belong in the same collection. Yet, rather than feeling disparate, Nguyen is able to lead us through the intersections that make these ideas inextricable. In “Lesson,” which introduces us to the speaker’s mother:

… For years we sat in silence

while she prayed & lit candles; asked ancestors to free me

from disease; again, blamed my father, that he taught me nothing

but desire & the desire to kill her—but still, I am surprised

when she turns to me and says, in a language I do not remember

being this soft, Because your lover is white, you are forgiven.

The mother-figure in these poems is painfully rendered. She who refers to the speaker’s white lovers as safety. She who the speaker talks about always translating into English, who the speaker also preemptively eulogizes, to “anticipate this grief by exhausting it / with music.” The mother appears in perhaps my favorite poem of the collection, “Changeling,” lamenting that a medication is making her fat, after she policed the speaker’s childhood weight:

It’s important to mention, I truly wanted to be beautiful

for her. In my dreams I am thin & if not thin, something better.

I tell my mother she is still beautiful & she laughs. The room fills

with flies. They gather in the shape of a small boy. They lead her

back to the mirror, but my reflection is still there.

The mother is just one figure that is written onto the speaker’s body. In fact, in relation to the title, Not Here could refer to the speaker’s body, his selfhood. The body is, in a way, not here, so often is it eclipsed by desire for the other, by its own failures, by memory and traumatic occlusions of memory.

I would be curious to know how Nguyen wants the violent eroticism in his work to be read. It’s one of my weaknesses as a reader, that I read narratives with shocking or excessive sexual force and think to myself, “that sounds nice.” But even correcting for that habit of mind, it seems to me that there is something active, something (if not joyful, at least) blazingly alive in the erotics of this book. The queerness, the striving for love in this book, is active. It is sad, but it is not doomed. It is a connection to life. Even in poems like the sardonically titled “Again, Let Me Tell You What I Know About Trust,” which maps violence between the speaker’s parents onto his adult sexual life, or the harrowing series of hook-up moments in a poem called “Hosting” where Nguyen writes:

… I can’t stop talking about desire,

I used to think of it as a pane of glass I would press my face against

& then one day it came, one day I fell through

the glass or the boy or the men in their many faces

This is Nguyen’s second poetry collection, and it does feel like the work of a young writer. I mean that there is an edge of clarity and urgency (even in pieces with intricate subjects) that reminds me of Sharon Olds’ early work. Nguyen’s most striking gift, for me, is finding moments of almost unbearable emotional pressure inside of the stories he is telling. You could buy this book for its clarity, its intersectionality, the specific truth-seeking which the poet has undertaken. All of those are excellent reasons to buy a book. I would buy it, instead, for its incendiary longing. Not Here does not tell you that it is safe, or right, to want. But it reminds you that for the living, there is no alternative.