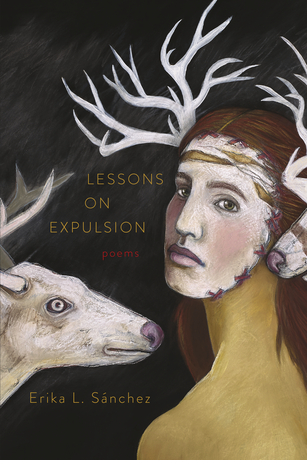

Lessons on Expulsion by Erika L. Sánchez (Graywolf 2017)

Reviewed by Jen DeGregorio, Guest Reviewer

Woman on the run. Woman in search of a home. Woman who finds nothing but damage wherever she lands, whether in a new nation or within the confines of her own mind. This is the restless speaker of Erika L. Sánchez’s first poetry collection, Lessons on Expulsion, a map of wanderlust and alienation, “where even my body is its own crumbling / country.”

This is indeed a book of crumbling countries, exploring how their dust can cling to us, weigh us down. Lessons on Expulsion weaves in and out of decrepit landscapes, often between the Chicago of the speaker’s childhood and back to Mexico, where her parents “crossed the border / in the trunk of a Cadillac,” as she recounts in “Crossing.” At a time when the Trump administration is demonizing immigrants—the undocumented in particular—this collection offers an important window into the indignities and injustices such people have historically faced as they struggle to survive as well as the psychological toll such struggle takes on them and their families. Sánchez viscerally captures the hardship of life as the child of undocumented immigrants: Though her parents slave “like a donkey” in factories, they cannot rise from the poverty that keeps their apartment “bristling / with roaches,” as she documents with excruciating tactility in “Girl.” The outside world offers no relief for the speaker’s discomfort. In the streets of Cicero, the Chicago suburb where she lives, lascivious men “whistle from their trucks,” call “mamacita” at her prepubescent body in the poem “Hija de la Chingada.” In “Orchid,” she recalls, at seven years old, watching strung-out “white prostitutes / in front of the Cove Motel lean into cars,” wondering: “Aren’t blonde women supposed to be beautiful?” Amid the sorrow that pervades this collection, the question registers as a moment of dark comedy, a deft jab at the myth of white female purity spread via Barbie dolls and the media’s obsession with towheaded beauties like Marilyn Monroe and Princess Diana. But the humor quickly dissolves into tragic irony as the reader remembers the trunk of that Cadillac, in which the speaker’s parents risked their lives to enter the United States, presumably to give their children a shot at the so-called American Dream. That dream, however, turns out to be a nightmare, in which its promised abundance manifests as its opposite: poverty and precariousness that drives the speaker to despair, as she reveals in “Girl”:

A man on the street tears the gold

necklace from your mother’s neck—

this is how you learn that nothing

will belong to you. In your mangled

language, you’ll count all the reasons

you wish to die,

These lines are heartbreaking. They also function as critique, a finger pointed at the reader who is perhaps nursing a passive melancholy about the state of the country under President Trump. As his administration continues its increasingly cruel immigration crackdown, people like the speaker and her family are placed at ever greater risk, not at the hands of jewelry-grabbing thieves but of ICE agents and government officials terrorizing their communities.

But if the speaker shames the reader for complacency, she does not let herself off the hook, recognizing her own escapism and flagellating herself for it. As the collection unfolds, the speaker leaves Cicero. At odds with her mother and “ghost-father” (as she calls him in “Hija de la Chingada”), she attempts to reinvent herself, a process she describes in “Amá” with the striking image of “my head peeking out from my own vagina.” She gets as far away as Spain, where she is studying abroad (presumably on a Fulbright Fellowship, as Sanchez did herself). But even gorgeous Madrid is “fresh with dog shit,” a metaphor for the soiled layers of guilt that keep her from enjoying her newly privileged existence. She ruminates about the disconnect between her life and her parents’: “while I’m at the Prado enjoying Goya and Velázquez, / my father is rising before the sun / to assemble air filters,” she writes in “Crossing.”

Perhaps it’s guilt that so often pulls the speaker’s mind toward her parents’ native Mexico in poems depicting the gruesomeness of the nation’s drug wars. In “Kingdom of Debt” “a roped mule / watches a man place a crown” on the “severed head” of a woman’s corpse. In “Las Pulgas,” we learn “how easily a body / dissolves in a vat / of acid.” In “Forty-Three,” “the body / is kindling. The body is a plastic / bouquet shriveled at a crossing.” Although the speaker has traveled to Europe—“to live among the civilized, / sip wine, and read Cervantes,” as she tells us in “Crossing”—she compulsively turns toward these atrocities across the Atlantic, as if picking at a scab. Is it that she cannot forgive herself for rising above the dire straits of her childhood? For criticizing Cicero when she knows there are worse places she could have been born? She doesn’t want to ignore the real suffering unfolding in Mexico, yet she understands that thinking about it is a rather useless activity; it does nothing to alleviate anyone’s suffering. Do her poems about Mexico’s drug wars amount to voyeurism, or a form of witnessing? Her parents would advise her to recognize, then simply enjoy, the relative cushiness of her circumstances. This idea was drilled into her as a child, which she articulates in “Girl,” wondering:

But what right do you have

to complain about anything,

with your clean socks and fat

little stomach?

As an adult, the speaker achieves much more than “clean socks.” In fact, her life has become quite glamorous, spent traveling the world with enough money and time to pursue her intellectual interests and passions. Isn’t that the American Dream? Aren’t we jealous? Aren’t we tempted to ask: Indeed, “what right” have you to “complain”? But this is an insidious question, with a pathological premise that gets at the root of both neoliberal and Trumpian logic. In neoliberalism, which has dominated U.S. policy and culture since the 1970s through the Obama administration, the individual is coerced into performing a bootstraps individualism that envisions success as a matter positive thinking. The ethos is encapsulated by corporate self-help author Will Schutz: “I choose my own life — my behaviour, thoughts, feelings, sensations, memories, health, everything — or I choose not to know I have a choice.”[1] Expressions of dissatisfaction are frowned upon, interpreted as signs of failure.[2] In Trumpism, this logic filters a twisted nationalism that prohibits political critique; think of Trump’s excoriations of the National Football League for defending players who have protested police brutality by kneeling during the national anthem during games, as if calling attention to a social problem is the problem itself.

But human pain cannot be reasoned away, nor erased by economic or careerist achievement. And we learn just how deep this speaker’s pain runs in “The Poet at Fifteen,” which explores her suicide attempt, an act she fears her hard-scrabble parents cannot fathom: “How do you explain what you have done? / With your hybrid mouth, a split tongue,” she wonders. The reader isn’t sure whether these suicidal feelings stem from chemical depression, some inciting incident, or both. The impoverishment and violence of Cicero was clearly traumatic. There are also hints of sexual violation. In “Self-Portrait,” Sánchez writes:

Under the torched

gown of sky, you ride me like a donkey.

And I let you. My screams are nothing

but windows painted shut.

Whether some specific assault has occurred or not, the speaker’s body moves amid ever-present danger — as do all women’s bodies, and the bodies of women of color in particular — represented by the catcalling men of “La Hija de la Chingada.” Yet in that poem it is not the men who earn the mother’s ire, but her daughter, who is made to feel responsible for whatever happens to her, as if she could guard herself against all unwanted advances: “You put the aspirin between your knees and hold it tight,” her mother warns, a poetic version of that sexist exhortation familiar to “nice girls” everywhere: “Keep your legs shut.”

What buoys this melancholic speaker throughout the collection is her deep intelligence, an ability to spin her own misery into art: “To the doctor I describe the pain as existential tumors,” she quips in “Crossing.” But her real sadness often thwarts her talents, deepening her plight: “In your flamboyant despair, you fail to suck the sweetness / from all that is good and holy,” she laments, beautifully, in “Letter from New York.” The collection ends eerily on “Six Months after Contemplating Suicide,” with the speaker feeling unable to go on:

How to negotiate

that strangling

mist, the fibrous

whisper?

It is difficult not to hear echoes of Sylvia Plath here. In “A Birthday Present,” Plath similarly imagines the air around her as a suffocating presence, a choking fabric:

If you only knew how the veils were killing my days.

To you they are only transparencies, clear air.

But my god, the clouds are like cotton.

Armies of them. They are carbon monoxide.

Yet Sánchez’s poem concludes wistfully, even hopefully. Whatever has been haunting the speaker has “passed through you / like a swift / and generous storm.” One could say the same thing about reading Lessons on Expulsion. Sánchez lifts the reader up and drags her through a series of punishing landscapes—physical and emotional—made of vocabulary that is by turns grotesque and exquisite, but always precise in its articulation of anguish, grief, and the less frequent pleasures of uncovering beauty in ugly places: “a choir / of crickets singing / behind your swollen eyes.”

[1] Schutz is quoted by Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval in their book, The New Way of the World: On Neo-Liberal Society, translated by Gregory Elliot and published by Verso, 2017.

[2] See Dardot and Laval

Guest Reviewer: Jen DeGregorio's poetry and prose has appeared in Apogee online, The Baltimore Review, The Collagist, PANK, The Rumpus, The Smart Set, Third Coast, Spoon River Poetry Review, WSQ (Women's Studies Quarterly), Yes Poetry, and elsewhere. She has taught writing, literature, and arts courses at colleges in New Jersey and New York. She is currently a PhD student in English at Binghamton University, State University of New York (SUNY), where she is a graduate fellow with the Human Rights Institute and an instructor with the Binghamton Poetry Project.