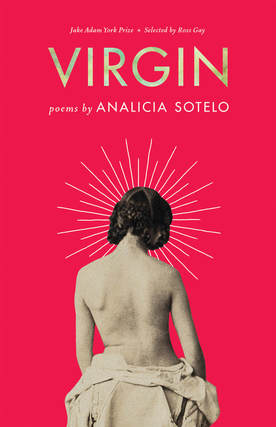

Virgin by Analicia Sotelo (Milkweed 2018)

Reviewed by Irène Mathieu, Staff Book Reviewer

Analicia Sotelo’s Virgin is stunning. Impeccably crafted and packed with sensual imagery, the book’s sectioned structure evokes formal ritual, such as a Catholic mass. Mass is ritual, is spiritual, is performance. The speaker – at times humorously self-deprecating, at times wielding controlled rage – is observer and interpreter. She watches interactions, including those in which she is involved, and draws out their social meanings through deft metaphors and frequent allusions to Greek mythology. Her conclusion, from the poem “Private Property,” is that “[w]e’re all performing our bruises.”

The role of an observer implies distance; the act of observation necessitates a positionality of remoteness – and in some cases, the observer is forced into such a space. This positionality is most evident in “You Really Killed That ‘80s Love Song,” in which Sotelo’s speaker says, “you can still hear your friend David / saying there’s no way you could be in love / if you’ve never been loved in the first place.” The implication is that romance or sex are essential knowledge – essential, even, to knowledge of the self. I think of how often our self-definition relies on our relationships with others – and if we haven’t experienced certain types of relationships, then who are we? The effect of this assertion, along with the choice to use the second person, is one of creating distance between even the speaker and herself.

This perhaps explains why the self seems lost in Virgin at times, such as in the poem “Purgatory Tastes Like Eggs.” The speaker finds herself with “a man, in my kitchen,” and therefore is “here with a stranger? / Like my father in the mirror in the middle of the night?” and later says, “[h]ello father. Goodbye father.” The reader is left to surmise that the boundaries of identity that separate “a man,” “my father,” and the speaker herself are unclear and shifting. It’s no accident that several of the characters from Greek mythology that appear throughout Virgin are known for their association with mazes, from Ariadne to the Minotaur.

In “I’m Trying to Write a Poem about a Virgin and It’s Awful,” the speaker discusses an unidentified “twenty-five-year-old” in the third person, whom we presume is the speaker of many of Virgin’s other poems. This double distancing creates the effect of clinical observation, as the speaker debates what “to say in her defense” and where to place her, the virgin who is the subject. Perhaps, then, a more accurate assessment of Sotelo’s speaker(s) is that she (or they?) are participant-observers – who, in ethnographic terms, collect qualitative data as part of the study of a culture, while simultaneously participating in that culture. Central to Sotelo’s success in Virgin is this quality of attentiveness, both inward and outward, that lends plausibility to statements such as, “[t]his is the darkness of marriage, / the burial of my preferences / before they can even be born” in the poem “South Texas Persephone.”

In the first section of Virgin, Sotelo turns this attentiveness to desire; the section is appropriately entitled “TASTE.” The carnal sensuality of food pervades these poems as a symbol of sexual and romantic desires. In “Summer Barbecue with Two Men,” the speaker watches as “[t]he man / I once wanted is grilling / these beautiful peaches,” and “judgment is a golden habañero margarita / with wings,” observing a kiss between “a man I know” and “a woman / whose fiancé is here somewhere.” In “Expiration Date,” the speaker asserts, “I’m a radish tonight, […] red and pungent.” In every poem of “TASTE,” food is shared in the company of others, so it becomes a universal language for these relationships’ hunger and confusion.

Greek mythology figures heavily in Virgin, whose fifth section, “MYTH,” places Ariadne and Theseus in a modern context, in “an apartment complex” with “A/C units” and “the flash of beer cans,” using FaceTime and listening to Kanye. The myth, Sotelo suggests in this section, is not so much mythological as it is an allegory for a timeless reality – the story of men mistreating or abandoning women, emotionally and physically. This isn’t to say that Sotelo’s Ariadne lacks agency. In the final poem of this section, “Ariadne Plays the Physician,” the speaker asserts, “I was the one who came to you / with a magnifying glass, / needing my Oxford credits / for the University of Someone Wants Me.”

Even earlier, in the book’s first section, the speaker in “South Texas Persephone” has “three heads: one / for speech, one for sex, / and one for second-guessing.” The three-headed dog Cereberus, guardian of the gates of Hades in Greek mythology, would let the dead in but prevent them from exiting the Underworld. So, too, might women in heterosexual marriages risk becoming complicit in their own oppression if they fail to interrogate and reform such institutions; this is “my set of sins.” Sotelo refuses to let her speakers off the hook, and they own up to their complicity. This evenhandedness of observation lends her poems an air of indisputability – as if they themselves are a new kind of mythology.

Sotelo’s speakers also wrestle with the ways in which desires and relationships are raced. In “Trauma with White Agnostic Male,” the speaker describes being exoticized:

You’ll mock a trio of mariachis,

a cer-vay-sa in your spidery hand.

That’s how you’ll say it: Sir Vésa

for love of my tender Latina outrage.

And in “Expiration Date,” the speaker stands at a social event “with the weeds brushing / their blond hair against my ankles.” The romantic or sexual exclusion the speaker feels is compounded by, and perhaps intimately connected to, racial exclusion – a connection that is deeply relatable. This deepens the exploration of power dynamics (which also hinge on gender and age) in Virgin, as the experience of otherness and exclusion is central to the idea of race.

The sections “PASTORAL” and “PARABLE” explore the speaker’s relationship with her parents. Woven throughout “PASTORAL” is the absence of the speaker’s father, including a poem called “Father Fragments (or, Yellow Ochre).” Earlier in the book, in the poem “Revelation at the All-Girls School,” the speaker remembers, “bad girls” who “you said [...] didn’t have fathers. Said / they needed you like God.” Throughout “PASTORAL,” male painters and thinkers, including Dalí, de Chirico, Pissarro, & Nietzsche, are invoked and compared to the speaker’s artist father. She fantasizes about “[o]ur two minds reunited in the yard.” Here “the idea of father” is reminiscent of an earlier observation – “[t]o admit I love you would be to admit / I love ideas more than men, / myself even less than ideas” (“Trauma with a Second Chance at Humiliation”). In the last stanza of “Father Fragments” are the following lines:

You may wish to make some connection

between father and lover here, as if your joke

could really be my life’s solution, or as if

I haven’t already done that, in a cuter way.

This preempts the reader’s Freudian assumptions, wresting the agency from the reader and placing it squarely back in the hands of the speaker. “Father Fragments” ends with, “the room was art itself / and I knew my father would always come back to it, / just as I would always come back to this room, this window,” complicating our assumptions about the relationship between father and daughter.

But even if fatherlessness is associated with godlessness in Virgin, at least, according to society, a mother has the power to transmit the divine. Maternal divinity is spelled out clearly in “My Mother as the Face of God”:

Mother, your likeness is not easy

or accidental. I am trying to understand it, trying

to become the opening

your light projects painfully through.

It’s “[w]hen I feel for men, I forget her, / set the death clock going” (from “Separation Anxiety”) that the speaker risks “the residue of a failed relationship,” but her mother, on the other hand, might be immortal: “[i]f she dies, I’ll leave her silhouette / to dry on wooden clips in the backyard.” If I were to wish for anything different about Virgin, it would be that this book were long enough to contain more of the maternal salve in “PARABLE.” Virgin derives its mythology more heavily from male artists and thinkers than it does female, but this is a product of the speaker’s environment and education, “so Westernized, how could I not / sink into it / & burn with questions” (from “My English Victorian Dating Troubles”).

Although shame ricochets through this book – the shame of desires, of embarrassing moments, of not “doing / what you should have done before” (from “You Really Killed That ‘80s Love Song”), of being a girl, then a young woman, of being in some way an other – Virgin is not a book of despair. In the final section, REST CURE, Sotelo’s speaker unequivocally denounces men’s “useless pink smiles” that “float like the aura of a migraine / on this weekend afternoon” (from “The Ariadne Year”). Humor intact, she has figured out how to save herself from “codependency” – in “The Single Girl’s Rest Cure,” the speaker debates “fiancés […] like physicians” for the right to diagnose and treat herself, a right for which she is wholly qualified after the emotional labor of the preceding sections. When the fiancé-physicians argue, “relax / sleeping helps & later, gardens & newborns,” the speaker counters that she is “hungry, but not that hungry.” It feels triumphant when the speaker in “My English Victorian Dating Troubles” pronounces, “I am bad with men / because I am deeply holy.” Sotelo’s speaker refuses to compromise or to be complicit – she has “[a] name they can’t forget / even if they wanted to.”