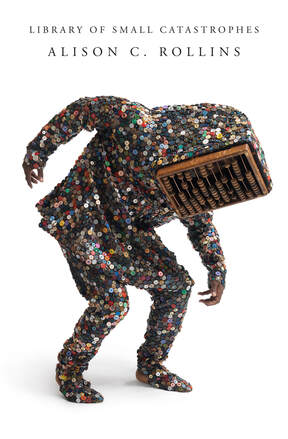

Library of Small Catastrophes by Alison Rollins

Reviewed by Irène Mathieu

In Library of Small Catastrophes (April 2019) Alison Rollins cements her place as a critical voice in contemporary poetry. The book, divided into three sections, is indeed a library of stories drawing on news clippings, archival papers, history, folklore, the biblical, and the personal. As in a library, the themes are not always ostensibly connected. Rather, the reader is invited into Rollins’ stream of consciousness, which flits from topic to topic in a variety of forms (couplets and quatrains; poems that are definitions, ars poetica, elegy, and ode), drawing connections, or not. Perhaps this is the most refreshing quality about Library – in a moment defined, in part, by the proliferation of so-called project books, this one feels more like an anthology of Alison Rollins, albeit with recurring themes that surface throughout the book.

The apparent disconnectedness of the themes – which include current events, historical anecdotes, catalogues of information, and presumably personal stories that span centuries and continents – is unsurprising given that Rollins herself is a librarian by trade. Themes appear and disappear somewhat unpredictably; it’s not unlike walking down a row of shelves and picking out the first spine that catches one’s eye. Library feels more spontaneous than curated. Libraries themselves are indeed everywhere in this collection – the poem “Report from inside a White Whale” takes place in “Biblioteca Vasconcelos in Mexico City,” and there are poems titled, “The Librarian,” “The Library of Babel,” “Portrait of a Pack Horse Librarian,” “Self-Portrait of Librarian with T.S. Eliot’s Papers,” and the title poem, among others.

Rollins’ literary and cultural influences span the globe – lines adapted from Fela Kuti and Walt Whitman make cameo appearances in “Water Get No Enemy,” a stirring poem for murdered environmental activist Berta Cáceres. The poem “Report from inside a White Whale” references the Biblical story of Jonah and the whale, as well as Bone Thugs-n-Harmony. The breadth of these references brings to mind another Whitman line: “I am large, I contain multitudes.” What books and people contain, Rollins seems to imply, cannot be assumed based on appearances.

The voice in Library at times feels distant and objective, the speaker cataloguing and defining the world around her, and at times is emotionally charged, almost devastatingly so. A recurring theme is the clarification of (mis)representations, as in “The Code Talkers.” In this poem the speaker translates from Navajo into Latin into scientific names into codes of more than one kind, and back again, in order to illustrate how war, nation-building, and even water are not always what they seem. The poem ends, “two roads diverged in a wood less traveled / a sheep in wolf’s clothing is at the fork.”

This obsession with representation is balanced by the simultaneous knowledge that mortality places limits on our ability to explain ourselves – here death’s inevitability engenders calm detachment in the speaker:

Be wary of how the translator twists

my words, these ruins he interprets as

alive. Why do you dread being forgotten?

Know that in some sense

you are already dead. (“To Whoever Is Reading Me”)

The reader can’t help but feel that for Rollins, the act of cataloguing, making meaning, and organizing these meanings is inherently pleasurable – after all, she is a librarian, and “this is good work” (“The Librarian”).

The body – and fantastic language describing it – figures prominently in Library. Rollins’ visceral imagery appears in the first poem of the collection: “[p]ink goosebumps waddle the lips” and “[s]pirit tells me my blouse is damp with milk. / The white mystery of doubt now leaks” (“A Woman of Means”). Ultimately this poem grants the reader consent into the speaker’s private world, concluding, “I give you permission to enter– / the opulence of this rabbit hole.” In the second poem, “Skinning Ghosts Alive,” the speaker strips away layers of family history hidden in the body, direct and “[s]traight as the line that reads you / your missing period and the knowing that this cannot / be allowed to continue.”

Then there’s the body situated in history, as in “The Fultz Quadruplets.” In this poem the black bodies of the eponymous quadruplets are spectacle, “God is a white man,” “[t]he white man is a doctor,” and “[t]he doctor is the one who / names things.” In this poem, agency is the dominion of white men, while “[t]heir mother, deaf and mute,” and Black, watches her children, “catalogued without permission.” Her children are in someone’s library. Similarly, “Child Witness” tells the story of the Saluda Old Town Treaty through the eyes of a young witness. The speaker of this poem, presumably a Native child, already understands the power imbalance between their body and the white man’s, and that “history / repeats its hunger.”

Library’s title poem, in four sections, is full of bodies: “Math is poetic in nature. You move / the decimal point two places to the right / to multiply black bodies / by the hundreds.” The poem moves to and through “this / shame of being black and American” and “a woman […] either stressed / or unstressed in theory.” The fourth and final section tells the story of a Black woman arrested for “stealing / urban romance novels.” It is a scene that contains violations on multiple levels – the officer who “reached his / hand insides her pants,” the vulnerability of this woman whose “wave of terror […] stained her face,” and the way her private desire is made public, suddenly and violently.

But are these “small” catastrophes? The title of the poem and entire book might be ironic, but I posit that Rollins means it in earnest. Scattered throughout the book are pithy lines that feel like proverbs – small nuggets of wisdom that put the stories throughout Library into perspective:

“We are never our own. / This is why we are so lonely.” (“Skinning Ghosts Alive”)

“Self-destruction a form of craft…All religion is art. Art is pain suffered and outlived.” (“The Path of Totality”)

“To love is to fear by choice, and fear is a particular religion.” (“The Librarian”)

“The reality that this life is pleasurably / painful is something that I can rely on.” (“All the World Began with a Yes”)

“[S]tory is to lie as boy is to man.” (“And Then There Were None”)

The final line of the book’s first section sums up these catastrophes: “So little has taken place” (“All the World Began with a Yes”).

Although, as Rollins implies, our catastrophes are insignificant in the grand scheme of the universe, her poems are most evocative when they turn to the interior. “Public Domain,” which appears near the end of the second section, straddles the line between distant archivist and grieving daughter: “You catalog by hand, playing librarian in your dead / mother’s house.” Through a series of objects discovered and sorted in the house, the reader is brought closer and closer to the speaker until the final stanzas:

Shaky cursive

her signature trademark. Upon the fall of a domestic

sphere, a pocketbook is emptied of all its valuables.

To become takes a long time. Blue spells are periods of

red where you pause, the body calculating the losses.

The poem “Oral Fixation” wends through the speaker’s childhood and “dysfunction in my family,” ending with these lines:

My social anxiety bites

his style, his need for absence, when I nurse

drinks in the heat of the empty night.

My lips suckle at the moon’s dry breast.

The stirring “Cento for Not Quite Love” and “original [sin]” are the only poems that contain no capitalization. Rollins’ choice to strip away all formality makes the stark vulnerability of these poems stand out.

While Library at times feels disjointed, there is a clear thread of family and personal histories, a familiar, intimate voice that appears periodically before the book turns down another opulent rabbit hole. Library of Small Catastrophes is most triumphant because of its range. Diligently cataloguing the worlds within and around her, Alison Rollins illuminates the poetics of librarianship.

The apparent disconnectedness of the themes – which include current events, historical anecdotes, catalogues of information, and presumably personal stories that span centuries and continents – is unsurprising given that Rollins herself is a librarian by trade. Themes appear and disappear somewhat unpredictably; it’s not unlike walking down a row of shelves and picking out the first spine that catches one’s eye. Library feels more spontaneous than curated. Libraries themselves are indeed everywhere in this collection – the poem “Report from inside a White Whale” takes place in “Biblioteca Vasconcelos in Mexico City,” and there are poems titled, “The Librarian,” “The Library of Babel,” “Portrait of a Pack Horse Librarian,” “Self-Portrait of Librarian with T.S. Eliot’s Papers,” and the title poem, among others.

Rollins’ literary and cultural influences span the globe – lines adapted from Fela Kuti and Walt Whitman make cameo appearances in “Water Get No Enemy,” a stirring poem for murdered environmental activist Berta Cáceres. The poem “Report from inside a White Whale” references the Biblical story of Jonah and the whale, as well as Bone Thugs-n-Harmony. The breadth of these references brings to mind another Whitman line: “I am large, I contain multitudes.” What books and people contain, Rollins seems to imply, cannot be assumed based on appearances.

The voice in Library at times feels distant and objective, the speaker cataloguing and defining the world around her, and at times is emotionally charged, almost devastatingly so. A recurring theme is the clarification of (mis)representations, as in “The Code Talkers.” In this poem the speaker translates from Navajo into Latin into scientific names into codes of more than one kind, and back again, in order to illustrate how war, nation-building, and even water are not always what they seem. The poem ends, “two roads diverged in a wood less traveled / a sheep in wolf’s clothing is at the fork.”

This obsession with representation is balanced by the simultaneous knowledge that mortality places limits on our ability to explain ourselves – here death’s inevitability engenders calm detachment in the speaker:

Be wary of how the translator twists

my words, these ruins he interprets as

alive. Why do you dread being forgotten?

Know that in some sense

you are already dead. (“To Whoever Is Reading Me”)

The reader can’t help but feel that for Rollins, the act of cataloguing, making meaning, and organizing these meanings is inherently pleasurable – after all, she is a librarian, and “this is good work” (“The Librarian”).

The body – and fantastic language describing it – figures prominently in Library. Rollins’ visceral imagery appears in the first poem of the collection: “[p]ink goosebumps waddle the lips” and “[s]pirit tells me my blouse is damp with milk. / The white mystery of doubt now leaks” (“A Woman of Means”). Ultimately this poem grants the reader consent into the speaker’s private world, concluding, “I give you permission to enter– / the opulence of this rabbit hole.” In the second poem, “Skinning Ghosts Alive,” the speaker strips away layers of family history hidden in the body, direct and “[s]traight as the line that reads you / your missing period and the knowing that this cannot / be allowed to continue.”

Then there’s the body situated in history, as in “The Fultz Quadruplets.” In this poem the black bodies of the eponymous quadruplets are spectacle, “God is a white man,” “[t]he white man is a doctor,” and “[t]he doctor is the one who / names things.” In this poem, agency is the dominion of white men, while “[t]heir mother, deaf and mute,” and Black, watches her children, “catalogued without permission.” Her children are in someone’s library. Similarly, “Child Witness” tells the story of the Saluda Old Town Treaty through the eyes of a young witness. The speaker of this poem, presumably a Native child, already understands the power imbalance between their body and the white man’s, and that “history / repeats its hunger.”

Library’s title poem, in four sections, is full of bodies: “Math is poetic in nature. You move / the decimal point two places to the right / to multiply black bodies / by the hundreds.” The poem moves to and through “this / shame of being black and American” and “a woman […] either stressed / or unstressed in theory.” The fourth and final section tells the story of a Black woman arrested for “stealing / urban romance novels.” It is a scene that contains violations on multiple levels – the officer who “reached his / hand insides her pants,” the vulnerability of this woman whose “wave of terror […] stained her face,” and the way her private desire is made public, suddenly and violently.

But are these “small” catastrophes? The title of the poem and entire book might be ironic, but I posit that Rollins means it in earnest. Scattered throughout the book are pithy lines that feel like proverbs – small nuggets of wisdom that put the stories throughout Library into perspective:

“We are never our own. / This is why we are so lonely.” (“Skinning Ghosts Alive”)

“Self-destruction a form of craft…All religion is art. Art is pain suffered and outlived.” (“The Path of Totality”)

“To love is to fear by choice, and fear is a particular religion.” (“The Librarian”)

“The reality that this life is pleasurably / painful is something that I can rely on.” (“All the World Began with a Yes”)

“[S]tory is to lie as boy is to man.” (“And Then There Were None”)

The final line of the book’s first section sums up these catastrophes: “So little has taken place” (“All the World Began with a Yes”).

Although, as Rollins implies, our catastrophes are insignificant in the grand scheme of the universe, her poems are most evocative when they turn to the interior. “Public Domain,” which appears near the end of the second section, straddles the line between distant archivist and grieving daughter: “You catalog by hand, playing librarian in your dead / mother’s house.” Through a series of objects discovered and sorted in the house, the reader is brought closer and closer to the speaker until the final stanzas:

Shaky cursive

her signature trademark. Upon the fall of a domestic

sphere, a pocketbook is emptied of all its valuables.

To become takes a long time. Blue spells are periods of

red where you pause, the body calculating the losses.

The poem “Oral Fixation” wends through the speaker’s childhood and “dysfunction in my family,” ending with these lines:

My social anxiety bites

his style, his need for absence, when I nurse

drinks in the heat of the empty night.

My lips suckle at the moon’s dry breast.

The stirring “Cento for Not Quite Love” and “original [sin]” are the only poems that contain no capitalization. Rollins’ choice to strip away all formality makes the stark vulnerability of these poems stand out.

While Library at times feels disjointed, there is a clear thread of family and personal histories, a familiar, intimate voice that appears periodically before the book turns down another opulent rabbit hole. Library of Small Catastrophes is most triumphant because of its range. Diligently cataloguing the worlds within and around her, Alison Rollins illuminates the poetics of librarianship.