Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl:

Diannely Antigua’s Ugly Music

Reviewed by Claudia Cortese

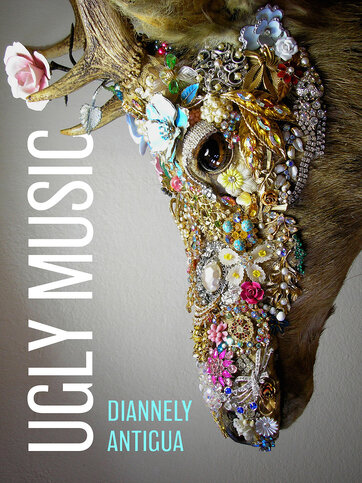

Reading Diannely Antigua’s first collection of poems, Ugly Music (2019), which won YesYes Books’ Pamet River Prize, I heard Sleater Kinney’s “Modern Girl” play in my head. Carrie Brownstein sings about how happy she is. Then, halfway through the song, she admits she’s lying—the defining emotion of this modern girl’s life is not “a picture of a sunny day” but, rather, a deep and endless hunger.

The speaker in Antigua’s Ugly Music performs the myth of the modern girl, simultaneously exalting the joys of living in this so-called “post-feminist world” while showing how much women’s lives are still mired in trauma and oppression. Like Brownstein’s modern girl, hunger defines Antigua’s speaker. She craves the sexual and economic freedom women are supposed to have in 2019. About halfway through the book, she declares:

I am at this desk to make money

so I can pay my rent, so I can afford

a room to have sex in. I ride

the J train to get to sex.

It’s at the Delancey stop. I played

a sad song while I waited for sex.

The flat tone in these lines implies that the job she’s working and the sex she’s having are less fun and glamorous than the media’s female empowerment narratives promised they would be. In “When Booty Call Turns into Love,” it becomes clear why the speaker is unsatiated:

. . . He names my vagina

Vonnie after a Madtv skit. We still

fuck while I twist my fro.

We walk to Popeyes at midnight.

I can feel the hunger

in my shoulders.

The speaker hungers not only for fried chicken but also for more pleasure. She twirls her hair while fucking, implying she’s bored, which makes sense—a man who names his lover’s vagina Vonnie surely lacks the skills to make her come. In the same poem, the speaker declares, “Life is a sad girl in a dick store.” In other words, the speaker is surrounded by countless dicks she may fuck, yet she’s sad. Though some of the sexual encounters in the book seem consensual, many of them seem unsatisfying, at best, and violent, at worst. In “Diary Entry #16: About Using My Body,” the speaker describes a sexual encounter with a boy who will “speak to [my pussy] better than all the boys / who have grabbed me and made videos // of me on a mattress.” Following the image of a boy giving the speaker pleasure is a description of moments that seem coercive and violent.

Before the speaker worked all day at a desk, she was raised on traditional gender norms. In “Praise to the Boys,” the adolescent speaker watched boys play basketball in the church parking lot “while Sister Priscilla taught the girls / to sew on buttons, stitch hems, iron collars.” In addition to Priscilla's gaze on the speaker’s hands as she sewed, God, too, surveilled her: “God watched / my hands feed the needle blue cloth bits at a time. He / watched my mouth, knew where I’d put it next, on the end / of a thread before pulling it through the eye.” God is a voyeur. He lusts for the speaker as the speaker lusts for the boys in the parking lot. The line break at “end” alludes to the fact that the speaker will one day wrap her lips around the end of a cock, graduating from the obedient girl sewing buttons to the modern girl fucking many lovers. The poem’s last lines imply that God watches the speaker mature into adulthood: “God saw the boy / lick a silent prayer, saw my back / curve in exalt.” The speaker’s lover prays by going down on her, feeling her holy orgasm on his tongue. These lines show that some of the speaker’s lovers have prioritized her orgasms, and those orgasms were a religious experience.

Modern girls reject the repression and patriarchy of their youth. They have great sex in their New York City apartments that they share with platonic, male roommates. “I am one of the few women in the complex who is unmarried and yet living with men . . . On the weekends, we scramble and fry [eggs] in coconut oil, like everyone is doing these days,” declares the speaker in “Of Highrise 88,” the book’s only prose poem. Modern girls eat coconut oil because it is full of “good fat,” as we have all heard the latest think pieces claim. Modern girls have careers and male roommates and lots and lots of orgasms. Except when they don’t—when they are sad and suicidal and not having lots and lots of orgasms. Instead, they are having sex that is bad, that borders on assault, that triggers memories of past trauma.

The book’s most chilling poems are the numbered diary entries that recur throughout, unfolding out of order and with entries missing. Diaries have become a metonym for women’s literature. For millennia in the West, women were precluded from publishing. Nevertheless, many educated women—especially affluent white women—kept diaries. Some of these diaries have been studied and published as a way to recover the buried voices of women from the past. For example, 17th century noblewoman Lady Ann Clifford’s diaries were published in the 1990s. We associate diaries with intimacy—the classic “dear diary” foreshadows the epistolary confession that follows. Antigua’s use of the diary form emphasizes the femininity and intimacy in her poems. Her poems, however, do not tell a wealthy white woman’s story. They explore coming of age in a working class, immigrant family, and navigating the world as a woman of color. When the speaker fears she’s pregnant, she exclaims, “Fuck you, pussy. / It’s been six days / waiting. Fuck you, / dry tampon . . . ” She imagines being saved from her pregnancy not by the white women often featured in Hollywood films about witches but by brujas who “squat / by a fire and stir it / with hierbas from the island.” Culture and media writer Giselle Defares explains the history and practice of Brujería:

The meaning of the Spanish word Brujería is witchcraft. The practitioners of the spirituality are brujas (female), brujos (male), or brujix (genderqueer). Modern Brujería is in its essence magic that is a blend of folklore, herbalism, African magic and healing, and Catholicism. It usually involves charms, divination, love spells and hexes. The historical significance of Brujería goes back to the early 15th century before indigenous communities were colonized by the Spaniards.[1]

“Diary Entry #1: Testimony,” the book’s sixth diary poem that falls about one third of the way through the book, opens with the speaker declaring that she hopes “no one reads this— / I was pregnant in the purple dress / when I escaped from the house.” She confesses that “[t]here was a surgery, / a bald head and a grieving.” In other words, the speaker had an abortion, which triggered flashbacks from her girlhood: “It’s the year 2000. // and I did all of my homework. The pastor / suspects nothing. I am 12. // We play the weird game.” This weird game is also referenced in “Picked:”

. . . I want to know

what to do with the memory—days of the week

underwear, the hand cupping the small cones

over my grey t-shirt, feeling

for the raised tip, pink eraser bud not yet

brown. . . .

She goes on to say that “[m]aybe he touched me to reruns // of The Brady Bunch, how I never trusted the father / in a room with them, the girls . . .” “Picked” is the only poem that directly details the speaker’s childhood abuse. Antigua refuses to sexualize the speaker’s trauma, which is what our culture wants from survivors—the details of the abuse that serve to titillate readers and “prove” that the trauma actually occurred. Survivors, of course, don’t owe anyone these details. Throughout the book, the speaker struggles with depression and suicidality, implying that the abuse had long-lasting effects.

The speaker attempts suicide and is hospitalized. Although this is certainly a serious issue, the speaker sometimes describes her mental health struggles in a deadpan, sardonic manner. In “How I Survived: An Erasure,” the speaker explains that “[t]herapists diagnosed me with a small amount of // stereotype,” implying that her desire to die is common for modern girls growing up in this white supremacist rape culture. The speaker opens “Diary Entry #20: Prognosis” with “So all SSRIs suck” and “There Is Nothing” with “[There is nothing] comparable to masturbating in a psych ward.” Both of these first lines give way to poems that explore the difficulties of mental illness. These poems do not downplay mental illness but, rather, address the speaker’s experiences—SSRIs are the worst, and she masturbated in a psych ward—with refreshing bluntness.

Many of our culture’s sad girl narratives center white women’s stories, unfortunately. The speaker in Antigua’s book, however, is the daughter of Dominican immigrants and has to navigate this country’s racism. In grade school, where they serve beans with hotdogs rather than with rice, she “learned that hair / wasn’t supposed to smell like fried pork chops / when the white kids formed a line / to whiff my braids.”

In addition to exploring the racism that she experienced, the speaker also delves into her own privilege. “My mother came here // on a plane and I thank a god,” the speaker says in “Immigration Story,” a poem about a boy whose mother died when the aluminum boat in which they were fleeing Cuba capsized. The poem could have remained a poem of witness in which the speaker describes the mother’s death, the boy’s survival which is also its own kind of death—for he’d lost his mother. The reader would then feel comforted by knowing that the speaker is a good person who bears witness to suffering. Antigua complicates this simplistic subject position by confessing: “And I feel like a bitch. // Because all I did was read a story, / then retell it on this page.” This gesture back to the speaker’s feelings of guilt does the difficult and necessary political work of both critiquing the horror and injustice of a senseless death and exploring one’s complicity in systems of power.

Diannely Antigua’s Ugly Music is a book for our times—sardonic, self-effacing, sincere. The speaker is a bad feminist in the ways that we are all bad feminists—negotiating our desire for equality with the many ways we are imperfect. Although many themes thread through this 92-page book—mental illness, reproductive rights, sexual trauma, suicidality, immigration, masturbation, to name a few—the book coheres around the speaker’s distinct voice and perspective. Diannely Antigua’s poems embody the struggles of a modern girl who confronts both her privilege and oppression, sexuality and sexual trauma. Readers will surely fall as deeply in love with these brilliant, modern girl poems as I have.

[1] “The Cultural Shift and Mainstream Acceptance of Brujería,” 8 May 2018, Bese.com