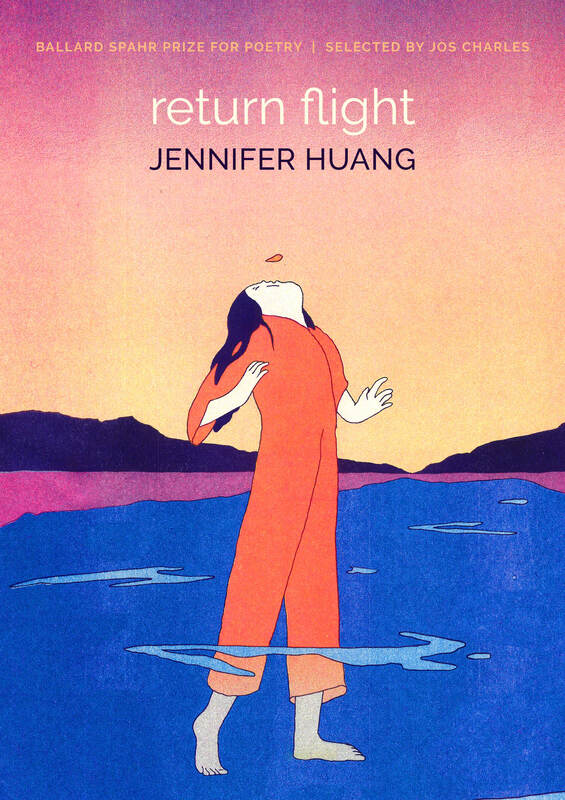

Only When You're Ready: Review of return flight by Jennifer Huang

Reviewed by Noel Quiñones

Truth is I didn’t want a man. Really,

I want to feel all of me

realize what is, what is;

my body, in existence; enough.

(From “Pleasure Practice”)

Jennifer Huang’s debut poetry collection return flight (Milkweed Editions, 2022) consists not of one flight but a journey of many flights. These poems land in real and mythological locales, visiting family and lovers along the way as they map out a life both individual and inherited, remembered and forgotten, expanding yet cyclical. Through the use of concise verse, breathless turns of phrase, and time looping forms, Huang creates a “space to / say not words; then, when she’s ready, many.” These poems take their time. They reflect with an airy smoothness that, at first glance, may seem to betray the trauma of their narrative, yet Huang showcases a deft hand, one which writes like water on water, gentle and yet striking when called to be a wave.

In Huang’s opening poem, “Departure,” the first in a series of three with the same title, the speaker acknowledges the confounding nature of their journey’s beginnings, writing:

Learned to fly before I could speak.

Before I could speak, I was left behind.

What I couldn’t express, was left behind.

I leave behind the things that don’t belong

To me. The red life vest floating out to sea.

Action precedes language, as what the speaker cannot express leads them to “fly”, presumably away. Being left behind was a trauma that the speaker couldn’t speak on at the time and so they left their belongings behind as well. Huang’s speaker begins this journey with no life vest, thrown out to sea with no language for trauma. In this way, this collection is a recollection, a speaker looping back to not only their past, but their family’s past in an effort to name what was left behind. The repetition of “before I could speak” and “left behind” structurally emphasize this looping, as Huang focuses not on the narrative and identity-based details of the journey, but the cycles that form and perpetuate them.

The next poem, “Customs”, begins to give us the complicated language for trauma: “My father saw and warned he’d break my arm, leaving / me to wonder if my arm was mine or his.” These lines highlight one of Huang's central questions in this collection: What do we do with the inheritances of our past? Are they grounded inside us? Can we fly away? Or, is it possible to record them and carve out a different flight plan?

Huang is not asking new questions, but their approach to them is fresh and dynamic. While there are many departures and landings within this collection, they are cyclical, not linear. Huang’s poetic landscape is transitory; readers visit memories, locales, and characters that, rather than build on each other, amass themselves within a bowl of experience. This is Huang’s secret ingredient: A wrestling with closeness in all its forms as their book’s structure. Near the end of “Customs,” Huang writes, “If I try hard enough, I can forget but / a part of me wishes to keep my hand on these memories, / to feel them to their ends.” This wish to both remember and forget is easier said than done. Throughout the collection, Huang describes the allure and danger of closeness, whether it be emotional, physical, spiritual, or cognitive. Here are a few lines from various poems that explore this motif:

“I am just that: a human who wants to be closer to god”

“what is it that makes us want to get close?”

“The past is faraway / though sometimes it stalks close"

“I climb the mountain, this man. His rocks I get close to—I could kiss. I take my ax and almost split.”

By interrogating various forms of closeness, as well as the very idea of it, Huang reveals the insidiousness of trauma: how it makes humans fear that which we also deeply desire. This complexity allows Huang to then navigate a more accurate portrayal of recollection, one where we do not suddenly gain understanding but rather get close, then closer, then too close and turn away, unable to handle the truths we find.

The speaker in “A Visit from Brother Ghost on the Harvest Moon” most clearly showcases the burden of uncovering and reflecting on learned truths. Huang writes:

What I know of him is what I’ve been told

on highways in the slow middle of the night

from a mouth too tired. The truth rolls out

a story sitting tight on the throat. The knife-

edge, moonlight slicing through him,

across me. I fear I’ll forget this. Tonight

I recite every detail to make a memory.

Here, memory is the calcification of truth, to be carried like luggage throughout our lives. Truth not only slices through the father figure, but the speaker as well, so much so the speaker fears a purposeful forgetting. And in this way, return flight equally charts the allure and danger not just of closeness but of distancing. In Huang’s eleven-page poem Layover, rightfully placed in the middle of the book, the speaker charts their experience as a second generation Taiwanese American visiting Taiwan with their father. Here, Huang utilizes white space to great effect, emphasizing both the closeness, “my face: a map / I apparently can’t hide. The shame, / then, at my delight: / I just want to be close” and the separation, “the distance between me and I grew / So you could love me as you’ve / Always imagined. I thought / That’s what you wanted. / Then, distance be- / Came infinite”, they feel towards Taiwan. The poem ends with a stirring image: “ outside two papayas touch” signifying a gentle shift in the narrative, as closeness begins to bloom.

Huang engages with their themes of closeness and distance not just narratively but formally as well. The first “Departure” poem, “poem for giving birth,” and “Self-Pleasure” all feature elements of alliteration, inversion, and chiasmus to showcase the movement of characters, ideas, and themes toward and away from each other at the level of the line. “Disaster” and “Individualism” do the same work narratively, by placing past and present timelines parallel to each other, creating a cyclical effect. Finally, the inherited forms Huang chooses are well suited to their themes, whether it be the tanka’s history of intimacy between lovers, the contrapuntal’s ability to be read in three different ways, or the zuihitsu’s combining of seemingly disparate narratives in one space.

Flight by flight, memory by memory, and word by word Huang’s speaker slowly circles their family’s past and their own present, in an effort to shift the order of action and language. In recollecting trauma, naming complexity, and embodying patience, the speaker changes. While Huang writes early on, “forgiveness before I can even shape the words.” At the end of the collection, this undeserved forgiveness to those who have hurt them shifts to demand for their hurt to end: “and then my voice, asking for it / to end, surprising even me.” Language does not erupt from the speaker; it slowly manifests itself. In the final poem, aptly titled "Manifest," Huang writes: “Laughter. Then mine, bursting / from my lips. A cry as I caressed / a sun-wet afternoon. For only / I was left and then I left.” Huang’s speaker is no longer spurred by trauma to fly; they now choose to leave. It is laughter that carries them on the next leg of their journey and beyond.

Noel Quiñones is a Puerto Rican writer, educator, and community organizer from the Bronx. He’s received fellowships from Poets House, the Poetry Foundation, CantoMundo, Tin House, and SAFTA (Sundress Academy for the Arts). His work has been published in POETRY, the Latin American Review, Kweli Journal, and is forthcoming in Tupelo Quarterly and Gulf Coast. He is the founder of Project X, a Bronx-based arts organization, a poetry book reviewer for Muzzle Magazine, and a current M.F.A. candidate in poetry at the University of Mississippi. Follow him online @noelpquinones.