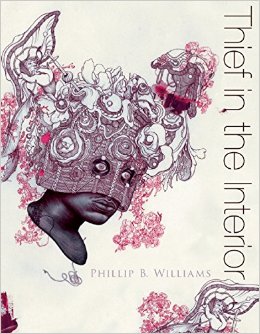

Thief in the Interior by Phillip B. Williams

Reviewed by Jacob Victorine, Book Reviewer

Alice James Books, 2016

Alice James Books, 2016

Phillip B. Williams’ debut collection, Thief in the Interior (Alice James Books, 2016) often defies description: experimental, narrative, documentary, visual (sometimes separately and other times all at once), and always linguistically stunning—even this long list of descriptors feels like an oversimplification. Williams takes tragedy and wrings beauty from it, yet his language is so graceful that the wringing feels more like water evaporating from cloth. And like water his poems take many forms, both through their subject matter and their shape on the page.

Williams’ speakers explore the historical atrocities committed against black Americans while navigating what it means to survive as a black, queer man in the treacherous present. Although they are unwavering in their vision, William’s poems are not singularly focused, as demonstrated by their many themes, such as the forms that love and sex take between two black men, the confines of masculinity and the white gaze, how a city like Chicago enacts itself on its citizens, the impact of an absentee father on his son’s life, and what it means to recount someone else’s story or to keep someone else’s secret.

In “Inheritance: Anthem,” a multipart poem that places text within tornadoes (or whirling records) of text, Williams navigates the many faces and voices of police brutality, one of which is the far too common scenario of a police officer unjustifiably pulling over a black driver: “The choreography is simple. Be followed. Be pulled/ over. Smile. He doesn’t smile back when he returns/ your license. Step out of the car” (II.1-3). Williams’ matter-of-fact diction demonstrates how police harassment is hammered into a black body until it becomes habitual, yet no less painful. The poem’s short lines mimic the truncated, tension-filled dialogue between officer and citizen, and this tension builds as Williams illuminates the stakes of the interaction: “When backup comes they both/ lecture you for thirty minutes. You were on your way to a funeral./ You will miss the open casket to avoid your own” (II.8-10). And isn’t this one of the reasons why the poem is an anthem—because the same brutal chorus is sung again and again?

Equally as powerful is the fifth section of the poem, which points the mirror at the white (literary) gaze: “I keep writing about Black bodies and You keep asking why, refusing to count/ the dead piling up at our doorsteps like phone books. They are so obtainable. They are/ a mirror in which You has never seen itself” (V.1-3). Williams addresses his readers directly, challenging them to address the violent repercussions of white supremacy instead of treating black bodies like “phone books” “piling up at our doorsteps,” just another ignorable nuisance. A few lines later, Williams expands his address to writers, as well: “I too wanted beauty without risk but the Black/ bodies fell into beauty to disturb it” (V.6-7). These lines feel particularly poignant in the current (and historical) literary climate that often praises white writers for their “universal” imagery and themes while criticizing writers of color for their “overly political” work.

“Witness,” a long-form documentary poem that fills up the entire second section of the book, explores the death of Rashawn Brazell, a young black man whose body parts were found in trash bags by transit workers along the tracks in the Nostrand Avenue subway station in Brooklyn, New York. In the second part of the poem, Williams flips lines backwards to unravel complex questions and meanings for the reader: “I called his name but heard my own/ come back. In the fog of my breath/ a prayer like wool too worn out to warm” (II.1-3) becomes:

How long does it take a city to discover

a prayer like wool too worn out to warm?

Come back. In the fog of my breath

I called his name but heard my own. (II.19-22)

Williams demonstrates an astounding technical mastery of poetic forms that goes far beyond form for form’s sake, as he repeats, reconfigures, and recontextualizes words and phrases in order to create continuity and multifaceted meanings, especially in his longer and serial poems.

Much of “Witness” finds empathy for Brazell through the speaker’s shared identity while also questioning the right of the writer to attempt to inhabit a body or voice that is not their own:

A friend tells me he was attacked with a half-

cup of cola and faggot, both thrown from

a passing car’s window late in the evening.

How enter a body not mine and speak

with the cadence of an activist with cola splashing

across sneakers? Narrative tries on its beauty,

its already-passed threshold into darker possibilities. (III.1-7)

Williams’ speaker gracefully connects personal and distant experiences while simultaneously acknowledging the artificiality of giving narrative to the death of someone he didn’t know. By placing himself and his speaker in this nuanced space, Williams creates “possibilities” for language and compassion that many writers struggle to even attempt.

Williams’ gift for navigating complex experiences and thoughts is also apparent in “Apotheosis,” which acts as a deconstruction of the intersection of the speaker’s black and queer identities:

Faggot was a thought

that snuck inside me, was put inside me,

and all the fields inside me turned Greek,

meaning tragic, meaning its beasts

were hybrid and hard to slay:

a faggot in the nigger, a nigger and a faggot

and thought both hollered I couldn’t let them go. (4-10)

Stunningly, Williams unpacks his own language for the reader, translating “Greek” to “tragic” to “hybrid and hard to slay” without losing the potential meanings of the initial word; it’s like leading someone through one universe while casually reminding them that other universes exist as well. Williams’ lines speak to the way language is enacted, and enacts itself, upon us—how hate speech is not only an attack on a person’s public identity, but also on their internal understanding of who they are.

Despite all of the tragedy throughout the book, Williams finds room for tenderness, even empowerment in poems such as “Do-Rag,” which explores the sexual relationship between two men, one who has not yet come to terms with his attraction to other men:

The sickle moon turns the sky into

a man’s mouth slapped sideways

to keep him from spilling what no one would

understand: you call me god when it

gets good though I do not exist to you

outside this room. Be yourself or no one else

here. Your do-rag is camouflage-patterned

and stuffed in my mouth. (23-30).

Williams’ imagery is precise without being arrogant, while enriching the reader’s understanding of the two men’s relationship: the moon that looks like a mouth slapped shut, the do-rag that is camouflaged like the men’s interactions and stuffed in the speaker’s mouth as a physical manifestation of the way he is silenced. And despite all of this hiding, despite the subtle and not-so-subtle forms of violence, Williams speaker is, by the end of the poem, a god who makes the rules: “Be yourself or no one else/ here” (28-29). Maybe this is the line that best represents the speakers in Thief in the Interior; despite all that they’ve witnessed, all that they’ve survived, they refuse to hide or run from what they’ve seen or who they are. What is braver or more beautiful than that?

Williams’ speakers explore the historical atrocities committed against black Americans while navigating what it means to survive as a black, queer man in the treacherous present. Although they are unwavering in their vision, William’s poems are not singularly focused, as demonstrated by their many themes, such as the forms that love and sex take between two black men, the confines of masculinity and the white gaze, how a city like Chicago enacts itself on its citizens, the impact of an absentee father on his son’s life, and what it means to recount someone else’s story or to keep someone else’s secret.

In “Inheritance: Anthem,” a multipart poem that places text within tornadoes (or whirling records) of text, Williams navigates the many faces and voices of police brutality, one of which is the far too common scenario of a police officer unjustifiably pulling over a black driver: “The choreography is simple. Be followed. Be pulled/ over. Smile. He doesn’t smile back when he returns/ your license. Step out of the car” (II.1-3). Williams’ matter-of-fact diction demonstrates how police harassment is hammered into a black body until it becomes habitual, yet no less painful. The poem’s short lines mimic the truncated, tension-filled dialogue between officer and citizen, and this tension builds as Williams illuminates the stakes of the interaction: “When backup comes they both/ lecture you for thirty minutes. You were on your way to a funeral./ You will miss the open casket to avoid your own” (II.8-10). And isn’t this one of the reasons why the poem is an anthem—because the same brutal chorus is sung again and again?

Equally as powerful is the fifth section of the poem, which points the mirror at the white (literary) gaze: “I keep writing about Black bodies and You keep asking why, refusing to count/ the dead piling up at our doorsteps like phone books. They are so obtainable. They are/ a mirror in which You has never seen itself” (V.1-3). Williams addresses his readers directly, challenging them to address the violent repercussions of white supremacy instead of treating black bodies like “phone books” “piling up at our doorsteps,” just another ignorable nuisance. A few lines later, Williams expands his address to writers, as well: “I too wanted beauty without risk but the Black/ bodies fell into beauty to disturb it” (V.6-7). These lines feel particularly poignant in the current (and historical) literary climate that often praises white writers for their “universal” imagery and themes while criticizing writers of color for their “overly political” work.

“Witness,” a long-form documentary poem that fills up the entire second section of the book, explores the death of Rashawn Brazell, a young black man whose body parts were found in trash bags by transit workers along the tracks in the Nostrand Avenue subway station in Brooklyn, New York. In the second part of the poem, Williams flips lines backwards to unravel complex questions and meanings for the reader: “I called his name but heard my own/ come back. In the fog of my breath/ a prayer like wool too worn out to warm” (II.1-3) becomes:

How long does it take a city to discover

a prayer like wool too worn out to warm?

Come back. In the fog of my breath

I called his name but heard my own. (II.19-22)

Williams demonstrates an astounding technical mastery of poetic forms that goes far beyond form for form’s sake, as he repeats, reconfigures, and recontextualizes words and phrases in order to create continuity and multifaceted meanings, especially in his longer and serial poems.

Much of “Witness” finds empathy for Brazell through the speaker’s shared identity while also questioning the right of the writer to attempt to inhabit a body or voice that is not their own:

A friend tells me he was attacked with a half-

cup of cola and faggot, both thrown from

a passing car’s window late in the evening.

How enter a body not mine and speak

with the cadence of an activist with cola splashing

across sneakers? Narrative tries on its beauty,

its already-passed threshold into darker possibilities. (III.1-7)

Williams’ speaker gracefully connects personal and distant experiences while simultaneously acknowledging the artificiality of giving narrative to the death of someone he didn’t know. By placing himself and his speaker in this nuanced space, Williams creates “possibilities” for language and compassion that many writers struggle to even attempt.

Williams’ gift for navigating complex experiences and thoughts is also apparent in “Apotheosis,” which acts as a deconstruction of the intersection of the speaker’s black and queer identities:

Faggot was a thought

that snuck inside me, was put inside me,

and all the fields inside me turned Greek,

meaning tragic, meaning its beasts

were hybrid and hard to slay:

a faggot in the nigger, a nigger and a faggot

and thought both hollered I couldn’t let them go. (4-10)

Stunningly, Williams unpacks his own language for the reader, translating “Greek” to “tragic” to “hybrid and hard to slay” without losing the potential meanings of the initial word; it’s like leading someone through one universe while casually reminding them that other universes exist as well. Williams’ lines speak to the way language is enacted, and enacts itself, upon us—how hate speech is not only an attack on a person’s public identity, but also on their internal understanding of who they are.

Despite all of the tragedy throughout the book, Williams finds room for tenderness, even empowerment in poems such as “Do-Rag,” which explores the sexual relationship between two men, one who has not yet come to terms with his attraction to other men:

The sickle moon turns the sky into

a man’s mouth slapped sideways

to keep him from spilling what no one would

understand: you call me god when it

gets good though I do not exist to you

outside this room. Be yourself or no one else

here. Your do-rag is camouflage-patterned

and stuffed in my mouth. (23-30).

Williams’ imagery is precise without being arrogant, while enriching the reader’s understanding of the two men’s relationship: the moon that looks like a mouth slapped shut, the do-rag that is camouflaged like the men’s interactions and stuffed in the speaker’s mouth as a physical manifestation of the way he is silenced. And despite all of this hiding, despite the subtle and not-so-subtle forms of violence, Williams speaker is, by the end of the poem, a god who makes the rules: “Be yourself or no one else/ here” (28-29). Maybe this is the line that best represents the speakers in Thief in the Interior; despite all that they’ve witnessed, all that they’ve survived, they refuse to hide or run from what they’ve seen or who they are. What is braver or more beautiful than that?