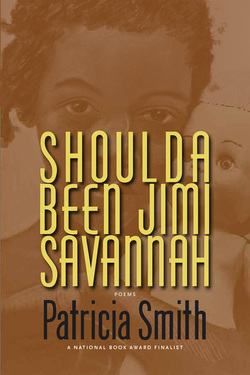

Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah by Patricia Smith

Reviewed by Kendra DeColo, Book Review Editor

There is something terrifying about watching the progression of an artist you love. Bound up in their success, you fear they may have given too much to their last project, that any unremarkable phrase could indicate an apex already achieved. This, I admit, is not a healthy view of creativity, belying a belief in talent as a finite, fragile thing. And yet, who hasn’t had their heart broken by a disappointing experimental album, been devastated by a team’s a post-championship year of losses? As my partner once braced himself for Pacquiao’s inevitable decline, it was with extreme caution that I broached Patricia Smith’s newest poetry collection, Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah.

Granted, there is no denying the virtuosity of Patricia Smith. Anyone lucky to have seen her perform live knows the power of her work on the page is as taut and incandescent as her presence—drama compressed to glinting syllables, unthinkable command and innovation of form, exquisite precision. And underneath the technique she is doing the hard work of making you feel. Who else could write Hurricane Katrina, placing us in the middle of the chaos and conversation? Who else to better position us inside impossible situations and get us to listen, seducing incantations in one hand, clarifying craft in the other?

Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah possesses the same focus and formal mastery of previous collections such as Blood Dazzler and Teahouse of the Almighty. Yet there is a heightened sense of risk in the project’s reach and scope, weaving the story of her family’s origin with the story of Motown, Northern Migration, and her own coming of age. Public and personal mythologies intersect and harmonize, building toward a narrative that is epic and encompassing, propelled by accumulation of detail and tightly-controlled lyricism.

Deeply personal and intimate moments of childhood are set against what feels like a rising wave of history as the book leads us through the pain of discovery to the woman Smith was to become. As shown in the gutting “13 Ways of Looking at 13” the collection itself is a testament to survival:

Like Mama and her mother before

her, you pulse on what is thrown away—gray hog guts stewed

improbable and limp, scrawny chicken necks merely

whispering meat. You will live beyond the naysayers,

your rebellious heart constructed of lard and salt, your

life labored long. You are built of what should kill you. (74)

The prophetic weight of these lines resounds throughout the collection’s architecture. In nearly every poem about childhood there is a sense of imminent threat, the speaker’s body vulnerable and exposed to her surroundings. Even the speaker’s birth is a scene of violence, told with an unflinching gaze and brutally spare detail:

Her legs are strapped flat,

and men are holding down her hands.

She wails. Not from hurt but from knowing.

There will be no running from this.

This child is a chaos she must name. (14)

As in Blood Dazzler where the most devastating depictions of Katrina are often subtle and understated, here the treacherousness of childhood is illuminated by domestic objects and simply told narratives. We see the speaker’s body change and develop through painful and gorgeously drawn sequences. Her first period is visceral: “You touch your forefinger to the fat clots in the blood,/ then lift its iron stench to look close, searching the the globs/ of black scarlet for the dimming swirl of dead children” (72). Explorations of sexuality are just as vivid, as in “First Friction,” so honest and raw it triggered an onslaught of murky flashbacks as if they were my own:

I don’t know how it started, how, wordlessly, Karen

and I tusseled skin, adjusted knee and cunt, naturally

knew the repeating mouth and its looping stanza.

She smelled like what I couldn’t stop swallowing. (43)

While we see elements of danger set in the city (sexual advances of men, society’s objectification of women), the source of violence is often embedded within the complexities of family and race. “Baby of the Mistaken Hue” gives physical action to what is shown throughout the collection as our culture’s shaming and sexualizing of black bodies. The lullaby lilt and authoritative syntax creates a chilling manifestation of this internalized voice, passed from mother to child:

Soaking a kitchen towel with the blaze

of holy water, I consider just what you are naked,

recoil at the insistent patches of midnight blanketing

your skin and I scrub, scrub, push the hard heel

of my hand deep into the dark, coax cleansing

threads of blood to the stinging surface, nod gently

in the direction of your Mama, don’t! (64)

Smith is most effective when she harnesses the music and electricity of her line. Freed up from the longer lines of narrative poems in which the syntax tends to sag, Smith’s lyricism is given room to wail within the constrained edifices of form. Some of the most successful poems in the collection are odes and elegies to Motown in which she employs formal technique and innovation such as the tercet rima, ghazal, limerick, and a crown of sonnets, just to name a few. Here she proves again her virtuosity, revealing through the limitations of compression and distillation what she achieves in accumulation: a mastery of voice and inventive diction; what Henry James called “passion at the pitch of perception.”

Some of the formal poems I found to be disappointing even as I found them technically astonishing. For instance the tribute to Stevie Wonder, “Looking to See How the Eyes Inhabit the Dark, Wondering About Light” is an incredible double sestina in which the end words and first words of each line are cycled through the traditional pattern. While I was appreciative and stunned by the poem’s footwork, the language felt sacrificed for the sake of form. Lines like, “Darkness strives to be his comfort. But he is obsessed by the need to look” or “Dark, desperately clutching, woos him, redefines beauty as the absence of light,” feel overwrought and clunky as the poem steels itself to slog through the repetition.

I couldn’t help imagining how much better the poem would be had Smith shortened the lines or shifted to syllabics, such as in “Have Soul and Die,” a poem dedicated to the singer Mary Wells: “So she wasn’t Diana. Who wanted to be/ all skeleton and whisper, hips like oil?” The compression allows for a clarity and stripped-down wisdom that the Stevie Wonder sestina lacks, resulting in this stunning finale:

she didn’t have to do a damn thing but be

black, have soul, and die, she’d puck those lips

just so, like she didn’t know how damn electric

it all was, and every word landed torn and soft,

like a slap from somebody who loves you. (52)

Where the collection forfeits crispness for overwhelming detail and repetition (it feels like a long book), it gains emotional tenor and depth through accrual. We have stood alongside the speaker through scrapes and brutal encounters. We have watched again how she survives and flourishes. The collection arrives at its most full and crystallized expression in the penultimate poem, “Thief of Tongues,” a portrait of her mother’s journey toward assimilation. Smith’s portrayal of her mother’s quest to lose her southern dialect is sober and heartbreaking.

When mama talks the southern swing of it

is wild with unexpected blooms,

like the fields she never told me about in Alabama.

Her rap is peppered with ain’t gots and I done beens

and he be’s just like mine is when I’m color among color.

During worship, when talk becomes song, her voice collapses

and loses all acquaintance with key, so of course,

it’s my mother’s fractured alto wailing above everyone

uncaged, unapologetic and creaking toward heaven. (99)

In the light-handed use of simile and metaphor we see the distance between the speaker and her mother, unmappable intimacies, bound together as much as they are isolated in their journeys toward self-realization. It is a cathartic poem, allowing us to stand along side the speaker as she forgives the past while mourning what was lost: the selves we lose along the way as we become who we are meant to be.

In the end, Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah neither allayed nor justified my original fears. Instead, the question of where a poet goes after achieving incredible success was re-framed. It’s not about linear progression or topping the latest achievement but fully realizing one’s voice and vision through risk. To love an artist is to embrace their journeys as much as we must treasure our own.

Granted, there is no denying the virtuosity of Patricia Smith. Anyone lucky to have seen her perform live knows the power of her work on the page is as taut and incandescent as her presence—drama compressed to glinting syllables, unthinkable command and innovation of form, exquisite precision. And underneath the technique she is doing the hard work of making you feel. Who else could write Hurricane Katrina, placing us in the middle of the chaos and conversation? Who else to better position us inside impossible situations and get us to listen, seducing incantations in one hand, clarifying craft in the other?

Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah possesses the same focus and formal mastery of previous collections such as Blood Dazzler and Teahouse of the Almighty. Yet there is a heightened sense of risk in the project’s reach and scope, weaving the story of her family’s origin with the story of Motown, Northern Migration, and her own coming of age. Public and personal mythologies intersect and harmonize, building toward a narrative that is epic and encompassing, propelled by accumulation of detail and tightly-controlled lyricism.

Deeply personal and intimate moments of childhood are set against what feels like a rising wave of history as the book leads us through the pain of discovery to the woman Smith was to become. As shown in the gutting “13 Ways of Looking at 13” the collection itself is a testament to survival:

Like Mama and her mother before

her, you pulse on what is thrown away—gray hog guts stewed

improbable and limp, scrawny chicken necks merely

whispering meat. You will live beyond the naysayers,

your rebellious heart constructed of lard and salt, your

life labored long. You are built of what should kill you. (74)

The prophetic weight of these lines resounds throughout the collection’s architecture. In nearly every poem about childhood there is a sense of imminent threat, the speaker’s body vulnerable and exposed to her surroundings. Even the speaker’s birth is a scene of violence, told with an unflinching gaze and brutally spare detail:

Her legs are strapped flat,

and men are holding down her hands.

She wails. Not from hurt but from knowing.

There will be no running from this.

This child is a chaos she must name. (14)

As in Blood Dazzler where the most devastating depictions of Katrina are often subtle and understated, here the treacherousness of childhood is illuminated by domestic objects and simply told narratives. We see the speaker’s body change and develop through painful and gorgeously drawn sequences. Her first period is visceral: “You touch your forefinger to the fat clots in the blood,/ then lift its iron stench to look close, searching the the globs/ of black scarlet for the dimming swirl of dead children” (72). Explorations of sexuality are just as vivid, as in “First Friction,” so honest and raw it triggered an onslaught of murky flashbacks as if they were my own:

I don’t know how it started, how, wordlessly, Karen

and I tusseled skin, adjusted knee and cunt, naturally

knew the repeating mouth and its looping stanza.

She smelled like what I couldn’t stop swallowing. (43)

While we see elements of danger set in the city (sexual advances of men, society’s objectification of women), the source of violence is often embedded within the complexities of family and race. “Baby of the Mistaken Hue” gives physical action to what is shown throughout the collection as our culture’s shaming and sexualizing of black bodies. The lullaby lilt and authoritative syntax creates a chilling manifestation of this internalized voice, passed from mother to child:

Soaking a kitchen towel with the blaze

of holy water, I consider just what you are naked,

recoil at the insistent patches of midnight blanketing

your skin and I scrub, scrub, push the hard heel

of my hand deep into the dark, coax cleansing

threads of blood to the stinging surface, nod gently

in the direction of your Mama, don’t! (64)

Smith is most effective when she harnesses the music and electricity of her line. Freed up from the longer lines of narrative poems in which the syntax tends to sag, Smith’s lyricism is given room to wail within the constrained edifices of form. Some of the most successful poems in the collection are odes and elegies to Motown in which she employs formal technique and innovation such as the tercet rima, ghazal, limerick, and a crown of sonnets, just to name a few. Here she proves again her virtuosity, revealing through the limitations of compression and distillation what she achieves in accumulation: a mastery of voice and inventive diction; what Henry James called “passion at the pitch of perception.”

Some of the formal poems I found to be disappointing even as I found them technically astonishing. For instance the tribute to Stevie Wonder, “Looking to See How the Eyes Inhabit the Dark, Wondering About Light” is an incredible double sestina in which the end words and first words of each line are cycled through the traditional pattern. While I was appreciative and stunned by the poem’s footwork, the language felt sacrificed for the sake of form. Lines like, “Darkness strives to be his comfort. But he is obsessed by the need to look” or “Dark, desperately clutching, woos him, redefines beauty as the absence of light,” feel overwrought and clunky as the poem steels itself to slog through the repetition.

I couldn’t help imagining how much better the poem would be had Smith shortened the lines or shifted to syllabics, such as in “Have Soul and Die,” a poem dedicated to the singer Mary Wells: “So she wasn’t Diana. Who wanted to be/ all skeleton and whisper, hips like oil?” The compression allows for a clarity and stripped-down wisdom that the Stevie Wonder sestina lacks, resulting in this stunning finale:

she didn’t have to do a damn thing but be

black, have soul, and die, she’d puck those lips

just so, like she didn’t know how damn electric

it all was, and every word landed torn and soft,

like a slap from somebody who loves you. (52)

Where the collection forfeits crispness for overwhelming detail and repetition (it feels like a long book), it gains emotional tenor and depth through accrual. We have stood alongside the speaker through scrapes and brutal encounters. We have watched again how she survives and flourishes. The collection arrives at its most full and crystallized expression in the penultimate poem, “Thief of Tongues,” a portrait of her mother’s journey toward assimilation. Smith’s portrayal of her mother’s quest to lose her southern dialect is sober and heartbreaking.

When mama talks the southern swing of it

is wild with unexpected blooms,

like the fields she never told me about in Alabama.

Her rap is peppered with ain’t gots and I done beens

and he be’s just like mine is when I’m color among color.

During worship, when talk becomes song, her voice collapses

and loses all acquaintance with key, so of course,

it’s my mother’s fractured alto wailing above everyone

uncaged, unapologetic and creaking toward heaven. (99)

In the light-handed use of simile and metaphor we see the distance between the speaker and her mother, unmappable intimacies, bound together as much as they are isolated in their journeys toward self-realization. It is a cathartic poem, allowing us to stand along side the speaker as she forgives the past while mourning what was lost: the selves we lose along the way as we become who we are meant to be.

In the end, Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah neither allayed nor justified my original fears. Instead, the question of where a poet goes after achieving incredible success was re-framed. It’s not about linear progression or topping the latest achievement but fully realizing one’s voice and vision through risk. To love an artist is to embrace their journeys as much as we must treasure our own.