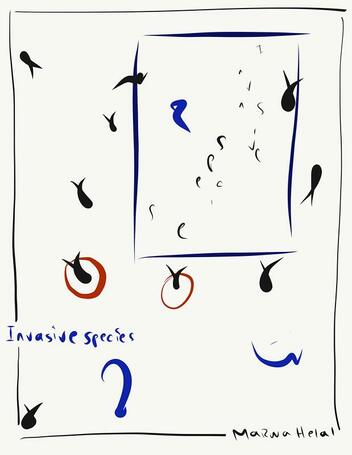

Invasive Species by Marwa Helal

(Nightboat Books, 2019)

Reviewed by Irène Mathieu

Invasive Species, the debut full-length collection by Marwa Helal, is genre-busting. It is poetry collection as collagist memoir, told in three sections through lyrical verse, prose narration, Google searches, snippets of immigration policy, paragraphs from news articles, definitions, letters, invented surveys, and clippings of newspaper commentaries about the ecological effects of invasive species like the common carp (Cyprinus carpio), all sprinkled liberally with footnotes and quotations. The diversity of texts used to construct Invasive Species mirrors the duality of the speaker’s Arab-American identity and her search for a home that is neither here nor there. The speaker’s displacement in Invasive Species is rooted fully in current events, as “T[---]p’s” immigration policies face off against an Egyptian-American (or American-Egyptian?) girl “stuck indefinitely in Egypt,” who blacks out after separation from her family. It’s also reflective of Helal’s journalism background, alternating between objective reporting and wrenching emotional lyricism. The patchwork of texts is this collection’s strangest and most impressive attribute.

Invasive Species starts by declaring exactly what it intends to do, with this epigraph from Chinua Achebe: “Let no one be fooled by the fact that we may write in English, for we intend to do unheard of things with it.” Helal repurposes English for her own intentions, with poems that read right to left, forms that are blocky and heavy, poems that refuse to bend or budge, poems that force the reader’s eyes to adjust. These poems have weight as well as momentum, as in the run-on quality of the three-page poem “the middle east is missing.”

The entire second section of Invasive Species, “Immigration as a Second Language,” comprises a memoiristic abecedarian in which each letter of the alphabet is the beginning of a narrative poem. They are impressively, prosaically present – hefty paragraphs whose sentences stretch across the page to touch both margins. This quality is particularly significant considering the fact that so much of this book is about displacement, which is the constant negotiation of the self’s absence from somewhere. This theme of displacement is introduced in the first section, where Helal writes, “make a space for me in your mind” and “before i left i wrote: where you from? where you from? where you / from? inside every empty closet of the homes i once / occupied” in the poem “the middle east is missing.”

In another poem, “let’s get this out of the way,” she asserts, “i find it impossible to compensate for these long absences in any / way. i have spent all of my life leaving, i have made art of it” and “i feel my absence, i feel my presence.” The effect of the abecedarian’s heft is twofold. Firstly, it reenacts for the reader the weighty alphabet soup of the labyrinthine immigration process, and secondly, it says, in the speaker’s own repurposed English, loud and clear, I AM HERE.

The longer poems in Invasive Species are interspersed with snarky, shorter works with titles like “in the first world” and “reality show,” the latter of which includes such lines as “weapons deal or no weapons deal” and “survivor: post-deportation edition.” These poems are clipped and terse in comparison to the sprawling excavations of the speaker’s identity and memory. This makes evident the fact that Helal is far more interested in constructing alternatives to empire via the self than in simply dissecting its all-too-obvious failings. Not that Helal shies away from diagnosis either; in the “X” of her central abecedarian she writes, “Xenophobia, it ought to be a diagnosable disease.”

What is so exciting about this book is the way that Helal makes her own rules – about language, about poetry – and defends them in the face of potential naysayers: “the poets / will say this poem is trash / but I don’t care” (from “poem for brad who wants me to write about the pyramids”). In this practice she becomes part of a long tradition of black and brown writers who repurpose the colonizer’s language for their art/survival. Helal asks, “who made this taxonomy? / unmake it” in “invasive species self-questionnaire” and later asserts, “i am trying to tell you something about how / rearranging words / rearranges the universe” in “generation of feeling.” Helal interrogates vocabulary – “American,” “Egyptian,” and “the Middle East” – in order to bluntly expose our complicity in others’ oppression, made material by (the idea of) borders themselves:

in this sense, the ‘middle east’ is not only missing,

it has a serious problem: its complicity in oppressing black and

palestinian people. this isnt to dismiss or diminish the oppression

of the peoples of the middle east but to say no revolution can

succeed without confronting this reality.

(from “the middle east is not only missing

it has a serious problem”)

Throughout Invasive Species there are multiple references to seeing/sight/vision. In “poem for brad who wants me to write about the pyramids” Helal writes “this is where the / poets will interject / they will say: show, dont tell / but that / assumes most people / can see.” In “poem for palm pressed upon pane” she writes, “when I say: this is the most / beautiful tree I have ever seen / and he says, all the trees in masr / are the most beautiful. this is how I learn to see.” When she writes about “an inner conflict. an unceasing / awareness of the gaze / a jihad of the naafs” in “invasive species self-questionnaire,” the reader is forced to consider the internal struggle that happens when the self identifies with both colonizer and colonized. Is it possible ever to be free of the colonizer’s gaze, in the U.S.A., in Egypt, in the entire world built on colonial white supremacy? “Zoom in. Zoom out. / Look. I’m trying to show you something,” the speaker instructs in the “Z” portion of Helal’s abecedarian.

This focus on gaze is reminiscent of DuBois’s theory of double consciousness, the “sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others” (from The Souls of Black Folk). Invasive Species grapples with seeing because willful failure to see others (and, in turn, the self) is central to the colonial/imperial project. You have to fail to see others in order to dehumanize them, to render them “other.” To fail to fully see others is, in and of itself, a dehumanizing process: “ah ah they thought us savages but did not have eyes enough to / see themselves” the speaker muses in “Invasius specius sapien reflects on the / consequences of synthetic apertures.”

If mis-seeing is how to separate people nearly into different “species,” then seeing – truly seeing – is the prescription for this rupture. That is the project behind Invasive Species’ preoccupation with seeing. By occupying the mind’s eye Helal is rewriting how we see ourselves and others. Helal pushes against artifice, or perhaps more accurately, she seems most interested in what happens when the fourth wall dissolves – when writer and audience actually see each other, eye to eye. In poems like “freewrite for an audience” she divests entirely from the paradigm that art, separate from life, is a performance about life. For Helal, art is life; in fact, it is survival, and she doesn’t mince words in dissecting this:

consider this part of my archive. when simone

said to be mindful of our archives something in me resisted the

idea. an archive felt like a performance, like i was supposed to be

performing the act of writing instead of living it, being it. but i

get it now. some things have happened to me recently that make

me want to treat the archive as an alibi.

(from “freewrite for an audience”)

When the distance is finally closed and vulnerability is raw on the page, there emerge clear moments of tenderness, like when Helal writes about offering the window seat on a bus to her motion sickness-prone brother, or her parents’ fierce love and advocacy. But underlying every poem in this book is a profound love for people outside her own family; as Helal writes in an untitled letter to immigration officials on page 51, “This is no longer about a visa for me; this has become an issue of human rights.” Indeed, in Helal’s “Epiepilogue” (ironically named, for after this the book re-ups with another 20 pages of poetry) she muses, “I’ve told you some secrets, played you my songs, and so we / are friends now.” Such is the intimacy of Invasive Species. It is a book that brings the reader close, so close, that they cannot help but see. By the end it’s unclear whether Helal has invaded our thoughts or if we have invaded hers, but it’s obvious that we’re better off for it.