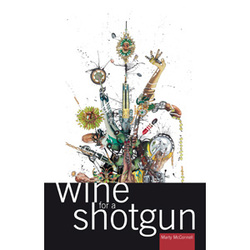

Wine for a Shotgun by Marty McConnell

Review by Jacob Victorine, Book Reviewer

I often hesitate when encountering a poetry collection that incorporates standards of the slam genre. As a poet who came up during the third or fourth wave of slam, a time when writing and performance styles have been appropriated endlessly, phrases such as “some days” immediately become triggers, echoing reused clichés. It’s not that I believe we should ignore our predecessors or that poets who slam can’t be as skilled on the page. It’s just that many poems that use slam phrasing often strike me as imitation, or even worse, as insincere.

For all I know, Marty McConnell, a poet who has been writing and performing expertly for years, may have created some of these standards. She has competed in the National Poetry Slam with numerous New York and Chicago teams, served as co-curator of New York’s slam bastion, Louder Arts for almost a decade, and has inspired more writers and performers than I can possibly name, many of whom have attended workshops with her current organization, Vox Ferus.

With that said, one of my initial reactions while reading through the opening pages of McConnell’s new, and first full-length collection, Wine for a Shotgun, was hesitation. Whenever I noticed a morsel of slam on my plate, I couldn’t help but flash back to the many trite poems I’ve seen performed over the years; not because McConnell’s poetry is trite—far from it—but because these moments were like the warped ringing of Pavlov’s dinner bell, conditioning me to dismiss a meal I hadn’t yet tried. After quieting these neuroses, however, I became continually impressed by the proficiency with which McConnell reinvents phrases and images that might be cliché in a less careful poet’s hands.

To read McConnell’s Wine for a Shotgun is to be thrust into a world of ever-shifting landscapes and changing identities. An out-of-tune piano is a metaphor for infidelity—each off-key note another night in the wrong person’s bed—and benign domestic objects become ominously alive right before a house crumbles. As many of McConnell’s poem titles indicate, tarot cards play a crucial role in the inspiration and construction of these poems, adding to the mystic elements that proliferate.

The importance of the supernatural becomes immediately apparent in the poem “Two of Swords,” in which McConnell’s speaker praises her lover’s body:

if I were a genius. or

an alchemist, or a man who could blow glass

into asphodels, into aliens

and chandeliers, the soft trigger

of your body might trust me. (10-14)

The speaker wishes to be not just a brilliant craftsman, but also a creator of the impossible: a man who turns base metals into gold, who turns glass into the sacred flower of Persephone. In McConnell’s world, magic rules beside myth.

This is not an idealized mythological world, however, and where there are gods there are also monsters. The speaker continues, “do not pull away. / if there are monsters here, I will string them / into the harp of my ribs” (21-23). These monsters creep throughout many of McConnell’s poems, often showing up when you least expect, haunting both the speaker and the reader. Yet, they do not go unchecked. In the world McConnell creates, the body is the instrument necessary to combat our betrayals, our shame, and our monsters. It is why McConnell’s speaker can string her lover’s monsters into her ribs and play them away like a mother singing her child back to sleep after a nightmare.

Monsters surface again in “Thine,” a poem focused on past infidelities, where McConnell reveals what they really are: ourselves. She writes: “I never meant to be a monster, / then quickly was. in fleeing, / we only become more ourselves / and it’s rarely good” (1-4). These monsters do not haunt us; we haunt ourselves. We are the creators of our own demons. Through lies and infidelity we become beasts of deception. Later in the poem she continues: “every monster / is lonelier than you. / every monster starts out / playing in tune” (40-42). Here McConnell establishes a metaphor that runs throughout the length of collection: the out of tune instrument as a symbol of infidelity. Wherever a monster lurks, a neglected instrument rests not far behind.

This mystical connection between betrayal and music becomes more evident in “Trespasses,” a poem of confession focused on family (and again) infidelity. McConnell writes:

the piano in our parent’s basement

goes untuned for years. I write my other sister

a letter that starts, do you feel destroyed

by the way we were raised? but it never

gets sent. (9-13)

Infidelity and deception are not the only parts necessary to build a monster; so is silence. This is why the piano goes untuned for years, why every monster “starts out / playing in tune” (41-42). There can be no music where there is silence, there can be no honest love, no honest sex where there is infidelity.

McConnell does not, however, write of infidelity, deception and silence through platitudes. These stories are emotional, resonant, and seem personal, as shown by the poem, “Deliver Us,” which begins: “there come such moments of redemption / and forgiveness that I can’t imagine / saying another word about my father’s infidelities / ever” (1-4). These stories of infidelities are the writer’s own. And although her speaker questions if she may one day come to a place where her father’s indiscretions no longer need expression, she continues to break her family’s history of silence by writing of it.

Throughout the collection we continue to see how family trauma impacts the environment surrounding McConnell’s speakers. In the poem “When Your Ex-Girlfriend’s Sister Corners you in the Kitchen,” she writes: “yes, she wants to know / what your queer status is. / and yes, the kitchen door did just shiver / on its hinges” (7-10). The speaker is so rattled by anger that even the room goes into a panic warning the speaker to escape. This is not the stereotypical domestic argument, however, but one of gender and sexuality, definitions that often define the self. Instead of simply writing about trauma, McConnell casts a spell on her speaker’s surroundings to show how trauma affects the way we experience our environment.

Themes of gender and sexuality proliferate throughout Wine for a Shotgun. In fact, it often seems these definitions help create the monsters lurking throughout the collection. To McConnell, freedom to tell the truth and freedom of the self are synonymous. And yet McConnell’s speakers are not beholden to terms of polite society. They are not victims, and they know that the supernatural is often a way to escape. In “The Chariot in Love” McConnell writes:

I’ve begun guessing

at the gender of lamp-posts. of couches.

of calendars. watching the jaws of men

on the train, studying their shoulders,

the shrug in their lean. I’ve become

something different now, too. (12-16)

Here, we see the complete merging of person and environment. Whereas earlier in the collection the environment surrounding McConnell’s speakers gains life through their pain, in this passage the speaker takes life from her environment in order to transform herself. McConnell’s speaker gains agency from her surroundings instead of being at their mercy.

This transformation beyond man and woman, straight and gay is what finally allows McConnell’s speakers to break free from definition, and free from their monsters. In “The Empress is a Drag Queen,” she writes: “the wig, / the womb, it’s all just passage. choose / a great name, speak it like a prayer” (16-18). McConnell and her speakers are less interested in what we are, than how we move. Life itself is a passage, and we are always changing, always moving through it. To deny the body its desires is to deny birth, to deny death, to deny the passage exists.

In the universe of Wine for a Shotgun, rescue is through the body and its music. In the final poem of the collection, “The World’s Guide to the Beginning” McConnell writes: “I learned kink / is another word for survival. learned to love / the body more for what it can do / than for what it is” (4-7). McConnell believes we must honor the body for its flesh and sinew, for the way it can wrap its itself tight around a loved one, for the sounds it makes, the way it trembles during orgasm, and not let it be silenced by those who claim to know what it is. She continues: “to make the body / a safehouse where all your monsters / get to be raucous” (22-24). To McConnell, we are both gods and monsters, who transform at the touch of a piano key, the first letter of a lie. Salvation is not found through denial, through silence—no, this is how we unleash our monsters on others—but through opening our arms, our doors, and letting our monsters live safely within us.

Wine for a Shotgun is a book of transformation, but not just for McConnell’s speakers. To read these poems is to be transformed from who or what you are to how you move through them, even if only for the time it takes to read the collection. McConnell proves that her background in slam cannot and will not define her or these poems, because like her speakers, they define themselves.