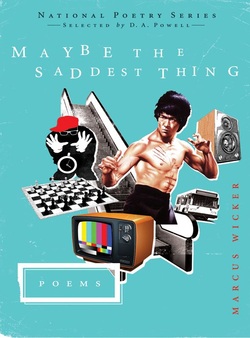

Maybe the Saddest Thing by Marcus Wicker

Review by Kendra DeColo, Book Review Editor

I’ve been waiting for Marcus Wicker’s debut collection Maybe the Saddest Thing, winner of the 2011 National Poetry Series, the way my partner waits for the next Pacquiao fight, the way we wait for any work of art to reveal better versions of ourselves, and I imagine I’m not the only one. He’s the kind of poet who makes you want to write, the way his music sounds like no one else’s, his images joyful and fearless, the way his heart translates into the wildest leaps you can imagine. This summer when a poet friend who thought I needed some cheering up read Wicker’s poem, “The Way We Were Made,” I realized how starved I’d been for a voice that honest, one that would convince me of the world’s beauty—“what is sweet in every wrong way”— not its flawlessness but the mess and ache.

Maybe the Saddest Thing is a collection that celebrates the messy and uncomfortable, from public gaffes (Justin Timberlake at the 2004 Super Bowl) to private moments of humiliation (middle school), praising the ways in which we fail. Failure is a sacred contract, giving us permission to enter the poems as imperfect beings, to stumble as we question and interact with issues the poems explore. While complicating and questioning these issues, the speaker always reveals his own shortcomings, using self-deprecation like the best stand-up comedians, to get us to look at ourselves.

The first half of the collection begins with a series of love letters addressed to cultural icons. The letters, while looking at the performance of race and gender in popular culture, are often about seeing one's own self in the other. In “Love Letter to RuPaul,” the line breaks hint at transgression as the speaker (who generally identifies as straight male) riffs on RuPaul’s strength and tenderness: “You have one of the longest, / thickest, most veined, colossal / set of hands that I have ever seen.” Wicker then moves from self-aware objectification of the body to a more intimate revelation:

…And still, that commercial

ravished me. How hard, to be sandwiched

between what and who you are, tickled

by every cruel wind, critic-voyeur

playing rough beneath your skirt. How

raw you must be. To sit before a camera,

legs uncrossed.

These lines echo what comes into the poems again and again, the distance between how we see ourselves and how we’re seen, and the courage it takes to live at this threshold.

In “Some Revisions,” the poem begins with a joke between friends about the speaker knowing every black person in Bloomington. The poem disrupts and restarts, revising itself as Wicker writes, “When you asked / Is it difficult to write about race? / I meant to say Hell yes. Yes. / Especially if you’re stilted. Like me. / I find it much safer to sit at home / and feign an understanding. But / to write race is to stare firm.”

Many people don’t write about race, I imagine, because it is so hard, because it feels like there should be a right thing to say, making it impossible to be authentic. The poem acknowledges this obstacle to authenticity in its form, beginning again and again, using the false start to push the poem past levels of comfort or predictability. When halfway through the poem the speaker says, “This isn’t working, is it?” it’s the moment of surrender when the poem opens up and exposes its heart.

The self-consciousness that makes poems about writing race so poignant and relatable shows up in other poems with equal force, conveying a sense of reaching and the tenuousness of language. In “Nature of the Beast,” the speaker questions the logic of his wife’s statement: “I cooked us dinner. Now, / you can wash the dishes,” using similes that devolve into wild associations:

No, it’s like

an aardvark snouting a barefoot kid into

a liquor store, saying, I sniffed the fire ants

from your sandbox. Now—about that brew.

The poem is playful and tender, creating a sense of limitlessness as each comparison unfolds. In other poems the self-consciousness focuses on the limitations of a poem, such as “Interrupting Aubade Ending in Epiphany:”

This poem is aware of its mistakes

and doesn’t care. This poem wants to be a poem

so bad, it’ll show you a young smitten pair

poised in an S on a down bed. The man inhales

the woman’s sweet hair and whole fields

of honeysuckle and jasmine bloom inside him.

He inhabits a breath like an anodyne and I think

I could call this poem an aubade if it detailed

new breath departing his mouth. I think I could

get away with that. Because who knows what

that even means? Maybe I mean that’s safer

than saying its straight.

The poem is at once gorgeous and self-conscious of its gorgeousness, a nod toward the unsayable, and how urgent it is that we say it. As in so many of the poems, Wicker is sincere while making fun of his earnestness, always risking the moment of “can I get away with this?” and doing it.

The poems’ vibrant and insanely gorgeous descriptions act as both engine and decoy, often going out on limb so far that the poem feels like it’s on the verge of snapping until another branch emerges. But often it’s the music that keeps the poem moving through the leaps, lines like:

The bass player does not matter. Nor

his right index—plucking

a note so deep dead skin ricochets

from a fat steel string to a woman’s

crystal glass of Grigio. No it doesn’t

matter. The trombone player’s lips split

clench & swell each dark hair

on my left big toe. No matter the alto

saxophonists other life. That this

gig saves us both tonight.

Likewise, Wicker’s exquisite narrative chops give the sense of associative meandering, coaxing us into forgetting that each tiny step has been choreographed, leading us to the place of astonishment where we look back and see the path we’ve been treading is illuminated.

“Stakes is High” is a poem I keep coming back to which balances humor with urgency. The poem begins with an amazing description of the father’s inability to have a conversation without getting political and ends with the speaker confronting his own inner racism. The poem uses imagination to complicate the narrative, going off of the father’s suggestion that something could be put in tap water to kill racists. It’s both hyperbolic and sober in tone, pivoting as the speaker faces the audience and himself: “And if I spent / one summer as a survey worker, if I phoned a woman / named Shanquita and assumed she lived in a hood, is that intra-racist? Is it double racist to assume / you assume she was black? To assume you are not?”

The poems in Maybe the Saddest Thing remind me of what Baldwin said about how writers reach a point where they must reinvent language. Wicker masterfully presses up against the limits of the figurative and lyric, presenting a voice in flux between dazzling and stripping down, showing us all that language can do and every beautiful way in which it fails.

What is so addictive about Wicker’s poems is that his wisdom and empathy go beyond seeing one’s self in another. He gets that “all humans want to understand everything / and for everyone to understand us” — that in the same poem a speaker can say: “As if I am not them” and then later, “And how sad it is because I am really not them” and how both are true.

After reading the collection, I realized what I had been waiting for was this feeling: to look up from the poem and say, it’s good to see myself again.

Maybe the Saddest Thing is a collection that celebrates the messy and uncomfortable, from public gaffes (Justin Timberlake at the 2004 Super Bowl) to private moments of humiliation (middle school), praising the ways in which we fail. Failure is a sacred contract, giving us permission to enter the poems as imperfect beings, to stumble as we question and interact with issues the poems explore. While complicating and questioning these issues, the speaker always reveals his own shortcomings, using self-deprecation like the best stand-up comedians, to get us to look at ourselves.

The first half of the collection begins with a series of love letters addressed to cultural icons. The letters, while looking at the performance of race and gender in popular culture, are often about seeing one's own self in the other. In “Love Letter to RuPaul,” the line breaks hint at transgression as the speaker (who generally identifies as straight male) riffs on RuPaul’s strength and tenderness: “You have one of the longest, / thickest, most veined, colossal / set of hands that I have ever seen.” Wicker then moves from self-aware objectification of the body to a more intimate revelation:

…And still, that commercial

ravished me. How hard, to be sandwiched

between what and who you are, tickled

by every cruel wind, critic-voyeur

playing rough beneath your skirt. How

raw you must be. To sit before a camera,

legs uncrossed.

These lines echo what comes into the poems again and again, the distance between how we see ourselves and how we’re seen, and the courage it takes to live at this threshold.

In “Some Revisions,” the poem begins with a joke between friends about the speaker knowing every black person in Bloomington. The poem disrupts and restarts, revising itself as Wicker writes, “When you asked / Is it difficult to write about race? / I meant to say Hell yes. Yes. / Especially if you’re stilted. Like me. / I find it much safer to sit at home / and feign an understanding. But / to write race is to stare firm.”

Many people don’t write about race, I imagine, because it is so hard, because it feels like there should be a right thing to say, making it impossible to be authentic. The poem acknowledges this obstacle to authenticity in its form, beginning again and again, using the false start to push the poem past levels of comfort or predictability. When halfway through the poem the speaker says, “This isn’t working, is it?” it’s the moment of surrender when the poem opens up and exposes its heart.

The self-consciousness that makes poems about writing race so poignant and relatable shows up in other poems with equal force, conveying a sense of reaching and the tenuousness of language. In “Nature of the Beast,” the speaker questions the logic of his wife’s statement: “I cooked us dinner. Now, / you can wash the dishes,” using similes that devolve into wild associations:

No, it’s like

an aardvark snouting a barefoot kid into

a liquor store, saying, I sniffed the fire ants

from your sandbox. Now—about that brew.

The poem is playful and tender, creating a sense of limitlessness as each comparison unfolds. In other poems the self-consciousness focuses on the limitations of a poem, such as “Interrupting Aubade Ending in Epiphany:”

This poem is aware of its mistakes

and doesn’t care. This poem wants to be a poem

so bad, it’ll show you a young smitten pair

poised in an S on a down bed. The man inhales

the woman’s sweet hair and whole fields

of honeysuckle and jasmine bloom inside him.

He inhabits a breath like an anodyne and I think

I could call this poem an aubade if it detailed

new breath departing his mouth. I think I could

get away with that. Because who knows what

that even means? Maybe I mean that’s safer

than saying its straight.

The poem is at once gorgeous and self-conscious of its gorgeousness, a nod toward the unsayable, and how urgent it is that we say it. As in so many of the poems, Wicker is sincere while making fun of his earnestness, always risking the moment of “can I get away with this?” and doing it.

The poems’ vibrant and insanely gorgeous descriptions act as both engine and decoy, often going out on limb so far that the poem feels like it’s on the verge of snapping until another branch emerges. But often it’s the music that keeps the poem moving through the leaps, lines like:

The bass player does not matter. Nor

his right index—plucking

a note so deep dead skin ricochets

from a fat steel string to a woman’s

crystal glass of Grigio. No it doesn’t

matter. The trombone player’s lips split

clench & swell each dark hair

on my left big toe. No matter the alto

saxophonists other life. That this

gig saves us both tonight.

Likewise, Wicker’s exquisite narrative chops give the sense of associative meandering, coaxing us into forgetting that each tiny step has been choreographed, leading us to the place of astonishment where we look back and see the path we’ve been treading is illuminated.

“Stakes is High” is a poem I keep coming back to which balances humor with urgency. The poem begins with an amazing description of the father’s inability to have a conversation without getting political and ends with the speaker confronting his own inner racism. The poem uses imagination to complicate the narrative, going off of the father’s suggestion that something could be put in tap water to kill racists. It’s both hyperbolic and sober in tone, pivoting as the speaker faces the audience and himself: “And if I spent / one summer as a survey worker, if I phoned a woman / named Shanquita and assumed she lived in a hood, is that intra-racist? Is it double racist to assume / you assume she was black? To assume you are not?”

The poems in Maybe the Saddest Thing remind me of what Baldwin said about how writers reach a point where they must reinvent language. Wicker masterfully presses up against the limits of the figurative and lyric, presenting a voice in flux between dazzling and stripping down, showing us all that language can do and every beautiful way in which it fails.

What is so addictive about Wicker’s poems is that his wisdom and empathy go beyond seeing one’s self in another. He gets that “all humans want to understand everything / and for everyone to understand us” — that in the same poem a speaker can say: “As if I am not them” and then later, “And how sad it is because I am really not them” and how both are true.

After reading the collection, I realized what I had been waiting for was this feeling: to look up from the poem and say, it’s good to see myself again.