Surviving a Rape Culture that Keeps Women and Femmes from Living Our Best Lives:

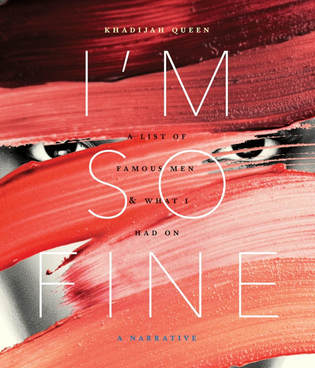

On Khadijah Queen’s I’m So Fine: A List of Famous Men and What I Had On (YesYes Books, 2017)

Reviewed by Claudia Cortese

Content Warning for sexual violence

While writing this review, I was texting with my bestie. The Leeann Tweeden accusations against Democratic Senator Al Franken had just broken. Tweeden stated that Franken coerced her into kissing him, and that she had photographic evidence of his assault: he posed in front of her, pretending to grope her breasts or perhaps actually groping her breasts. I texted my friend immediately and wrote, “That reminds me of the time those dudes took off my shirt and groped me while I was passed out.” And he responded, “Oh yeah, I remember that.” Then our text-convo meandered to other topics, such as wanting to have abs and our gym workouts. I didn’t cry or panic when I recounted that night to my bestie. I just shrugged and went back to writing this review. This isn’t to say that being assaulted or harassed or whatever—not sure what to name what happened to me—wasn’t traumatizing. I woke the next morning not remembering the night before, terror-panic filling my body. When I found the photo the boys had snapped of me—shirtless, one of their heads in my breasts, my eyes closed and mouth agape, I realized why I’d woken up feeling terrified. But I kept hanging out with those guys—cruising the cul-de-sacs of Canton, Ohio while listening to Nirvana or 2Pac. What they had done to me was horrifying—robbing me of my consent and treating me like a doll to play with—and completely unremarkable. I don’t know one woman or femme who hasn’t been assaulted, and most have been assaulted multiple times. Khadijah Queen’s I’m So Fine: A List of Famous Men and What I Had On depicts the experiences of living in a rape culture with chilling accuracy—how it means that sexual and physical violence are so common as to become more unremarkable than the outfits one wears. That night, I had on Jnco jeans, a purple and white striped tank top, a black choker, and scuffed black Converse. I remember more clearly what I had on than what happened to me.

The narrator in Queen’s book ostentatiously performs her femininity by detailing her outfits in each and every piece. These descriptions are, in a word, delicious. I turned the pages anxiously, excited to see what the narrator would have on next. She wears a “burgundy vegan leather tank top with a peplum hem & a black midi skirt & low-heel slightly-over-the-knee leather boots.” She wears “a purple jersey midi dress & purple silk crop top with sequins & a sheer scarf hem that [falls] to [her] waist & spaghetti straps no bra & silver stiletto sandals with ankle ties.” She wears a “white Guess t-shirt . . . tucked into high-waisted ankle-zipped acid-washed jeans” and knows she looks “fly.” One of the most common ways women and femmes are blamed for our own assaults is by focusing on what we were wearing. It seems absurd—that no one really thinks that way anymore—but, actually, many people still do. This rape myth is rooted in the fallacy that men are animals who cannot control themselves when a woman reveals “too much skin.” It is also rooted in the idea that women’s bodies, as well as femininity in general, are pathological. Therefore, the more we ornament our bodies, highlighting and celebrating our femaleness, the more likely we are to be punished for being female. By detailing the clothes her narrator has on, Queen refuses to pathologize femininity, refuses to let her narrator be blamed and shamed simply because she wears stylish clothes and looks fly, refuses to diminish the art and artistry of fashion—which we often disparage because we associate fashion with femininity.

Each story in Queen’s book is unpunctuated and in a prose block with no paragraphs, trauma never rupturing the everyday experiences of a Los Angeles girl’s life in the 80s and 90s. The stories don’t pause when the narrator or someone she knows is beaten, harassed, raped. They don’t ruminate on the healing process, the lessons learned from pain, don’t give the sentimental comfort of a path out of the forest. Rather, the stories unfold at lightning-quick speed, leaping from describing cute outfits to being assaulted to hanging out at the food court in the mall. In “Ohmygod but when we saw DeVante on the escalator,” the narrator and her friends spot DeVante from Jodeci and “everybody freaked out screaming except me.” The speaker recounts that “there were six of us that day ditching science because the teacher was a perv on top of being boring.” The poem describes meeting DeVante, the outfit the narrator is wearing—“a sundress white with blue flowers and some brown clogs”—and how “all the cheerleaders hated” her and her friends “because the football players started to sit with us at lunch,” but it never describes why the teacher is a perv. In fact, it’s easy to miss the reference to the teacher because we never learn what he has done to students—groped them? assaulted them? harassed them? It is just another fact of their lives that unfolds beside the fact that the teacher is boring, that they have spotted DeVante, that the narrator is wearing a sundress, and that she and her crew make the cheerleaders mad with jealousy. When the narrator says that the “teacher was a perv on top of being boring,” it’s clear that the details of the teacher’s transgressions are as boring to her as the man himself. Her flippant tone implies that most guys are pervs, so why bother with the unextraordinary details of their perviness?

This book is in the voice of a young African-American woman. In most of the stories, she is in her teens and twenties. Queen perfectly captures a young woman’s voice—sometimes annoyed, sometimes afraid, and always wonderfully honest. I laughed out loud more times than I can count while reading this book. I could hear the narrator’s voice, which Queen crafted perfectly—capturing her narrator’s cadence and diction. In one piece, the narrator recounts working at a fast food restaurant in which her boss, a woman named Lena who has “a slight goatee & crooked glasses,” mistreats her and her sister, who also works at the restaurant. Lena makes them “do the dirtiest work” to punish them for being cute and young. The day the narrator quits, she meets LL Cool J:

I’m sure I looked a hot poor mess but oh well we got to see LL lick them lips & smile &

sign our posters & CDs I sent the poster to my niece in Michigan & the CD wasn’t all

that good but I did like that one song with Boyz II Men we bumped that in the Oldsmo & I

still miss that car’s hellified bass

Most of us don’t speak with perfectly-placed transitions and topic sentences, telling linear tales that have a clear beginning, middle, and end. Rather, we meander. We wander. When the narrator leaps from describing that time she worked at a fast food restaurant in which her boss Lena harassed her and her sister because Lena likely had internalized misogyny that stemmed from the way our culture had body-shamed her to that day the narrator met LL to the car she once owned that had “hellified bass,” Queen captures the way friends talk to each other. Like my text-convo with my bestie that meandered from that time I was groped and photographed to wanting to have abs to the machines we use at the gym, Queen’s stories meander, which creates intimacy between the reader and narrator. While reading the book, I felt as if the narrator were sitting beside me, telling me stories from her day and from her girlhood. In another brilliantly funny tale, the narrator spots Q-Tip from A Tribe Called Quest and says that “he had immaculate skin & is way taller than I thought & hella fine so I don’t even remember what I wore that day I mean shit.” The conversational tone throughout the book reveals how even though the narrator has experienced sexual trauma, racism, poverty, she is not defined solely by her suffering. One of the most common ways liberals dehumanize others is by reducing people to their oppression and marginalization, which implies that our pain is what defines us. Yes, Queen’s narrator has been hurt in numerous ways, and we should not diminish the many traumas of living in a white supremacist rape culture, but she has also seen Prince live and worn super-cute outfits and is raising a son she loves dearly.

By the end of the book, the narrator is an adult woman and has moved from L.A. She goes out on a date with a man she describes as a “narcissistic sociopath” and asks, “[W]here is the law against men that fine and that crazy.” During the date, the fine-looking sociopath tells the narrator about “his multiple cars & failed pro football career & travels to China where he had adventures with sex traffickers & drug dealers & later . . . the breakup with his Chinese baby’s mother who he called his former weed bitch.” As I write these words down, I cannot stop laughing. The descriptions of this self-involved man who won’t stop talking about his bizarre past, which ends with him calling the mother of his child his “former weed bitch,” are hilarious because we all know this guy exists. Many of us have dated him, or hung out with him, or perhaps have even been in a relationship with him. Anyone who has gone out with men will likely nod their heads in recognition when reading about this trainwreck of a date. Unfortunately, though, narcissistic men are not always as harmless as the guy in this story. Queen’s book reveals what happens when a culture gives men so much unchecked power over women and femmes. It leads many men to feel entitled not only to dominate a conversation during a date, but also to dominate women and femme’s bodies.

I had planned to conclude this review by quoting the moment towards the end of the book when the narrator wonders how much of her “real house with its rust & clutter & unframed prints & desiccated parsley in the crisper” she should let people see. By house she means the self, and by desiccated parsley, she means “her history of poverty” and her traumatic past. I wanted to finish by reflecting on how beautifully, hilariously—though also with pain and vulnerability—this book narrates the speaker’s experiences. As I was wrapping up the review, my phone beeped, and Twitter alerted me that Lena Dunham issued a statement defending Girls’ former writer Murray Miller, a white man, who Aurora Perrineau, a Black actress, has accused of raping her. Dunham famously tweeted that women don’t lie about being raped, but now claims that Perrineau is lying about her assault. Dunham’s racism, unfortunately, is unsurprising. We live in a country where white women make up only 20% of missing persons and yet 65% of the news coverage on people who have gone missing focuses on white women. The Weinstein scandal has, in part, gotten so much traction because many of the victims who have come forward are white women. And the women of color he harassed and assaulted—including Lupita Nyong'o—have not received nearly as much media coverage as the white women.

Tales of harassment and assault are dominating the news cycle right now. We are hearing the stories of Hollywood celebrities, but not the stories of fast food workers. We are mostly hearing the stories of wealthy, white cis women, but not the stories of women of color, of trans women, of fat women (I say “fat” in a neutral, not pejorative, way—“fat” has been reclaimed by the body positive movement, but that’s a whole other essay!). Queen’s book details the experiences of being harassed on music video sets and on city busses, by men who are rich and by men who are homeless. Queen reveals that it’s not one industry that’s broken or one kind of person who’s likely to be a perpetrator or a victim. The disease that is rape culture has affected all of us in some way, but we are only hearing the stories of those who are most privileged, most powerful. Now—more than ever—we need to read Queen’s chillingly realistic stories narrating the experiences of a woman trying to survive—and thrive—in a culture that wants to keep her from living her best life.

*The statistic about missing white women was taken from “Missing White Woman Syndrome: An Empirical Analysis of Race and Gender Disparity in Online News Coverage of Missing Persons” by Zach Sommers.

While writing this review, I was texting with my bestie. The Leeann Tweeden accusations against Democratic Senator Al Franken had just broken. Tweeden stated that Franken coerced her into kissing him, and that she had photographic evidence of his assault: he posed in front of her, pretending to grope her breasts or perhaps actually groping her breasts. I texted my friend immediately and wrote, “That reminds me of the time those dudes took off my shirt and groped me while I was passed out.” And he responded, “Oh yeah, I remember that.” Then our text-convo meandered to other topics, such as wanting to have abs and our gym workouts. I didn’t cry or panic when I recounted that night to my bestie. I just shrugged and went back to writing this review. This isn’t to say that being assaulted or harassed or whatever—not sure what to name what happened to me—wasn’t traumatizing. I woke the next morning not remembering the night before, terror-panic filling my body. When I found the photo the boys had snapped of me—shirtless, one of their heads in my breasts, my eyes closed and mouth agape, I realized why I’d woken up feeling terrified. But I kept hanging out with those guys—cruising the cul-de-sacs of Canton, Ohio while listening to Nirvana or 2Pac. What they had done to me was horrifying—robbing me of my consent and treating me like a doll to play with—and completely unremarkable. I don’t know one woman or femme who hasn’t been assaulted, and most have been assaulted multiple times. Khadijah Queen’s I’m So Fine: A List of Famous Men and What I Had On depicts the experiences of living in a rape culture with chilling accuracy—how it means that sexual and physical violence are so common as to become more unremarkable than the outfits one wears. That night, I had on Jnco jeans, a purple and white striped tank top, a black choker, and scuffed black Converse. I remember more clearly what I had on than what happened to me.

The narrator in Queen’s book ostentatiously performs her femininity by detailing her outfits in each and every piece. These descriptions are, in a word, delicious. I turned the pages anxiously, excited to see what the narrator would have on next. She wears a “burgundy vegan leather tank top with a peplum hem & a black midi skirt & low-heel slightly-over-the-knee leather boots.” She wears “a purple jersey midi dress & purple silk crop top with sequins & a sheer scarf hem that [falls] to [her] waist & spaghetti straps no bra & silver stiletto sandals with ankle ties.” She wears a “white Guess t-shirt . . . tucked into high-waisted ankle-zipped acid-washed jeans” and knows she looks “fly.” One of the most common ways women and femmes are blamed for our own assaults is by focusing on what we were wearing. It seems absurd—that no one really thinks that way anymore—but, actually, many people still do. This rape myth is rooted in the fallacy that men are animals who cannot control themselves when a woman reveals “too much skin.” It is also rooted in the idea that women’s bodies, as well as femininity in general, are pathological. Therefore, the more we ornament our bodies, highlighting and celebrating our femaleness, the more likely we are to be punished for being female. By detailing the clothes her narrator has on, Queen refuses to pathologize femininity, refuses to let her narrator be blamed and shamed simply because she wears stylish clothes and looks fly, refuses to diminish the art and artistry of fashion—which we often disparage because we associate fashion with femininity.

Each story in Queen’s book is unpunctuated and in a prose block with no paragraphs, trauma never rupturing the everyday experiences of a Los Angeles girl’s life in the 80s and 90s. The stories don’t pause when the narrator or someone she knows is beaten, harassed, raped. They don’t ruminate on the healing process, the lessons learned from pain, don’t give the sentimental comfort of a path out of the forest. Rather, the stories unfold at lightning-quick speed, leaping from describing cute outfits to being assaulted to hanging out at the food court in the mall. In “Ohmygod but when we saw DeVante on the escalator,” the narrator and her friends spot DeVante from Jodeci and “everybody freaked out screaming except me.” The speaker recounts that “there were six of us that day ditching science because the teacher was a perv on top of being boring.” The poem describes meeting DeVante, the outfit the narrator is wearing—“a sundress white with blue flowers and some brown clogs”—and how “all the cheerleaders hated” her and her friends “because the football players started to sit with us at lunch,” but it never describes why the teacher is a perv. In fact, it’s easy to miss the reference to the teacher because we never learn what he has done to students—groped them? assaulted them? harassed them? It is just another fact of their lives that unfolds beside the fact that the teacher is boring, that they have spotted DeVante, that the narrator is wearing a sundress, and that she and her crew make the cheerleaders mad with jealousy. When the narrator says that the “teacher was a perv on top of being boring,” it’s clear that the details of the teacher’s transgressions are as boring to her as the man himself. Her flippant tone implies that most guys are pervs, so why bother with the unextraordinary details of their perviness?

This book is in the voice of a young African-American woman. In most of the stories, she is in her teens and twenties. Queen perfectly captures a young woman’s voice—sometimes annoyed, sometimes afraid, and always wonderfully honest. I laughed out loud more times than I can count while reading this book. I could hear the narrator’s voice, which Queen crafted perfectly—capturing her narrator’s cadence and diction. In one piece, the narrator recounts working at a fast food restaurant in which her boss, a woman named Lena who has “a slight goatee & crooked glasses,” mistreats her and her sister, who also works at the restaurant. Lena makes them “do the dirtiest work” to punish them for being cute and young. The day the narrator quits, she meets LL Cool J:

I’m sure I looked a hot poor mess but oh well we got to see LL lick them lips & smile &

sign our posters & CDs I sent the poster to my niece in Michigan & the CD wasn’t all

that good but I did like that one song with Boyz II Men we bumped that in the Oldsmo & I

still miss that car’s hellified bass

Most of us don’t speak with perfectly-placed transitions and topic sentences, telling linear tales that have a clear beginning, middle, and end. Rather, we meander. We wander. When the narrator leaps from describing that time she worked at a fast food restaurant in which her boss Lena harassed her and her sister because Lena likely had internalized misogyny that stemmed from the way our culture had body-shamed her to that day the narrator met LL to the car she once owned that had “hellified bass,” Queen captures the way friends talk to each other. Like my text-convo with my bestie that meandered from that time I was groped and photographed to wanting to have abs to the machines we use at the gym, Queen’s stories meander, which creates intimacy between the reader and narrator. While reading the book, I felt as if the narrator were sitting beside me, telling me stories from her day and from her girlhood. In another brilliantly funny tale, the narrator spots Q-Tip from A Tribe Called Quest and says that “he had immaculate skin & is way taller than I thought & hella fine so I don’t even remember what I wore that day I mean shit.” The conversational tone throughout the book reveals how even though the narrator has experienced sexual trauma, racism, poverty, she is not defined solely by her suffering. One of the most common ways liberals dehumanize others is by reducing people to their oppression and marginalization, which implies that our pain is what defines us. Yes, Queen’s narrator has been hurt in numerous ways, and we should not diminish the many traumas of living in a white supremacist rape culture, but she has also seen Prince live and worn super-cute outfits and is raising a son she loves dearly.

By the end of the book, the narrator is an adult woman and has moved from L.A. She goes out on a date with a man she describes as a “narcissistic sociopath” and asks, “[W]here is the law against men that fine and that crazy.” During the date, the fine-looking sociopath tells the narrator about “his multiple cars & failed pro football career & travels to China where he had adventures with sex traffickers & drug dealers & later . . . the breakup with his Chinese baby’s mother who he called his former weed bitch.” As I write these words down, I cannot stop laughing. The descriptions of this self-involved man who won’t stop talking about his bizarre past, which ends with him calling the mother of his child his “former weed bitch,” are hilarious because we all know this guy exists. Many of us have dated him, or hung out with him, or perhaps have even been in a relationship with him. Anyone who has gone out with men will likely nod their heads in recognition when reading about this trainwreck of a date. Unfortunately, though, narcissistic men are not always as harmless as the guy in this story. Queen’s book reveals what happens when a culture gives men so much unchecked power over women and femmes. It leads many men to feel entitled not only to dominate a conversation during a date, but also to dominate women and femme’s bodies.

I had planned to conclude this review by quoting the moment towards the end of the book when the narrator wonders how much of her “real house with its rust & clutter & unframed prints & desiccated parsley in the crisper” she should let people see. By house she means the self, and by desiccated parsley, she means “her history of poverty” and her traumatic past. I wanted to finish by reflecting on how beautifully, hilariously—though also with pain and vulnerability—this book narrates the speaker’s experiences. As I was wrapping up the review, my phone beeped, and Twitter alerted me that Lena Dunham issued a statement defending Girls’ former writer Murray Miller, a white man, who Aurora Perrineau, a Black actress, has accused of raping her. Dunham famously tweeted that women don’t lie about being raped, but now claims that Perrineau is lying about her assault. Dunham’s racism, unfortunately, is unsurprising. We live in a country where white women make up only 20% of missing persons and yet 65% of the news coverage on people who have gone missing focuses on white women. The Weinstein scandal has, in part, gotten so much traction because many of the victims who have come forward are white women. And the women of color he harassed and assaulted—including Lupita Nyong'o—have not received nearly as much media coverage as the white women.

Tales of harassment and assault are dominating the news cycle right now. We are hearing the stories of Hollywood celebrities, but not the stories of fast food workers. We are mostly hearing the stories of wealthy, white cis women, but not the stories of women of color, of trans women, of fat women (I say “fat” in a neutral, not pejorative, way—“fat” has been reclaimed by the body positive movement, but that’s a whole other essay!). Queen’s book details the experiences of being harassed on music video sets and on city busses, by men who are rich and by men who are homeless. Queen reveals that it’s not one industry that’s broken or one kind of person who’s likely to be a perpetrator or a victim. The disease that is rape culture has affected all of us in some way, but we are only hearing the stories of those who are most privileged, most powerful. Now—more than ever—we need to read Queen’s chillingly realistic stories narrating the experiences of a woman trying to survive—and thrive—in a culture that wants to keep her from living her best life.

*The statistic about missing white women was taken from “Missing White Woman Syndrome: An Empirical Analysis of Race and Gender Disparity in Online News Coverage of Missing Persons” by Zach Sommers.