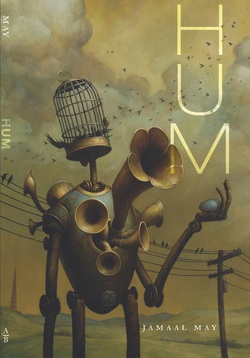

Hum by Jamaal May

A Review by Corrina Bain, Book Reviewer

Jamaal May’s Hum (Alice James, 2013), winner of the 2012 Beatrice Hawley Award, is a startlingly beautiful debut, long anticipated by those who know of May via his chapbook press, Organic Weapon Arts, or his videos, or the magic of his performance. The collection is fueled by compelling contrasts between a difficult, often ugly reality, and an aesthetic capable of finding beauty in anything. It is a book of contrasts between innocence and experience, and a book of place, intimately and proudly about Detroit (and how satisfying it is that Detroit be shown every inch as mythic as Blake’s London.) May is also doing one of the most urgent works of the poet, to show the fractal containment of people and their environment—what befalls the city comes into the lives of individual people.

The ugly and the beautiful are not just counterposed, they rely on each other, as in the poem “Hum for the Stone”:

A boy feels a broken brick

strike between shoulders.

The next stone breaks

against his nose as he turns,

and if not for the many ribbons

of blood sliding between

fingers, one could think

he was doubled over

with laughter. Celebration

in the convulsions.

Beyond the tension between loveliness and violence, the author’s well-crafted, deliberate language and his wild reality make Hum crackle with life. The lyric and the narrative also inter-rely upon each other. Poems that would otherwise be vehicles of uncomplicated grief become larger, more ornately worked, beautiful and mythic, as is the case in “The Sky, Now Black With Birds,” a meditation on the hate crime murder of James Byrd and the execution of Troy Davis:

I wanted Brewer dead.

So dead, my tongue swelled fat with hexes, so fat

I wonder how forgive could ever fit inside my mouth.

Somehow it’s always there, fluttering in the larynx

of Ross Byrd—the man whose father was dragged,

urine soaked, by Brewer behind a truck.

Watch him say it.

Forgive.

I swear,

the word has feathers.

Several times in the book, May is able to give us rich gifts of this nature, valorizing human lives which a pseudo-generic white American consciousness is just as happy to invisibilize and devalue.

In a parallel thread, May introduces us to the characters of several children, each of them bringing their freshness, but never with the easy fiction that innocence will save you. In the opening poem:

Boy with a safety pin-clasped

bath towel of a cape

tucking exacto knife into sock.

Boy with rocks…

…

Boy with a guardian

daemon and flawless skin.

The children here let us see ourselves, our adult emotions rendered at once literal and symbolic. The children are illustrations. Play is not innocent but a precursor of adult struggles for competence and image. For example, in a later poem: "In a backyard, a boy learns a boomerang / doesn’t come back to you only your location."

In “On Metal,” we see the fusion of the mechanical and human, as the auto industry fails to offer its former protection to a group of mechanics who can’t wrangle a car’s computerized parts:

No one is happy to learn what an afternoon of chafed

knuckles, metal on skin, no longer solves. What can’t

be pulled from the steel tangle under a hood

*

As a reviewer part of my job is to try to needle books apart instead of just liking them immensely. So what can I needle away from May? If there is anything missing from the collection, and it is probably not even missing but rather obscured, it is a quality of romantic intimacy. Somehow, the ‘eye’ which May turns toward Detroit, towards machines, towards familial love, detailed and exacting and also nearly flighty in its lyricism, does not show us May in love or his love objects clearly. “Hum of the Machinist’s Lover” is essentially cute, (“Eyes flicker // like flashlights are behind / them because flashlights are / behind them”) although it does dovetail nicely with the Detroit/machine theme. “Macrophobia” and “I Do Have a Seam” are the other obvious love poems in the collection, and both of them address a woman who is virtually invisible, assumed to be present. The emotion rings less true, or at least less accessible, than the feeling evoked in the poems on other subjects.

Is this a significant problem with the collection? I don’t find it so. Any number of people write lucid, believable love poems (probably everyone who makes it through their adolescence manages to write, or at least be capable of writing, a really good love poem once in their lives.) The gifts May has when he conveys the pain and rapture of the city and its machines, or when he gestures towards death, are at least as rich as conventional love poems and far more unique.

Also, although I have so thoroughly convinced myself of my correctness that I hardly feel the need to keep saying it, May’s work is further proof of the nonsensical distinction between academic and performance poetry. May’s command of language, his deliberateness, and his facility with form are impossible to ignore. And how was he driven to arrive at that level of mastery? How did he get through an MFA with the urgency and wildness and humanity of voice still intact? I would argue, through a background in performance and poetry slam. Language is a tool that May is using, not to make ornaments, but to externalize his reality, to give himself to the reader.

So here again, we find a mutual reliance, between craft and urgency, between voice and text, just as May finds “celebration in the convulsions,” the reliance between beauty and ugliness, between innocence and experience, between violence and – what? What really is the opposite of violence? To know, intimately, the inner life of what you had hurt. To long for peace, while knowing that peace is impossible.

The ugly and the beautiful are not just counterposed, they rely on each other, as in the poem “Hum for the Stone”:

A boy feels a broken brick

strike between shoulders.

The next stone breaks

against his nose as he turns,

and if not for the many ribbons

of blood sliding between

fingers, one could think

he was doubled over

with laughter. Celebration

in the convulsions.

Beyond the tension between loveliness and violence, the author’s well-crafted, deliberate language and his wild reality make Hum crackle with life. The lyric and the narrative also inter-rely upon each other. Poems that would otherwise be vehicles of uncomplicated grief become larger, more ornately worked, beautiful and mythic, as is the case in “The Sky, Now Black With Birds,” a meditation on the hate crime murder of James Byrd and the execution of Troy Davis:

I wanted Brewer dead.

So dead, my tongue swelled fat with hexes, so fat

I wonder how forgive could ever fit inside my mouth.

Somehow it’s always there, fluttering in the larynx

of Ross Byrd—the man whose father was dragged,

urine soaked, by Brewer behind a truck.

Watch him say it.

Forgive.

I swear,

the word has feathers.

Several times in the book, May is able to give us rich gifts of this nature, valorizing human lives which a pseudo-generic white American consciousness is just as happy to invisibilize and devalue.

In a parallel thread, May introduces us to the characters of several children, each of them bringing their freshness, but never with the easy fiction that innocence will save you. In the opening poem:

Boy with a safety pin-clasped

bath towel of a cape

tucking exacto knife into sock.

Boy with rocks…

…

Boy with a guardian

daemon and flawless skin.

The children here let us see ourselves, our adult emotions rendered at once literal and symbolic. The children are illustrations. Play is not innocent but a precursor of adult struggles for competence and image. For example, in a later poem: "In a backyard, a boy learns a boomerang / doesn’t come back to you only your location."

In “On Metal,” we see the fusion of the mechanical and human, as the auto industry fails to offer its former protection to a group of mechanics who can’t wrangle a car’s computerized parts:

No one is happy to learn what an afternoon of chafed

knuckles, metal on skin, no longer solves. What can’t

be pulled from the steel tangle under a hood

*

As a reviewer part of my job is to try to needle books apart instead of just liking them immensely. So what can I needle away from May? If there is anything missing from the collection, and it is probably not even missing but rather obscured, it is a quality of romantic intimacy. Somehow, the ‘eye’ which May turns toward Detroit, towards machines, towards familial love, detailed and exacting and also nearly flighty in its lyricism, does not show us May in love or his love objects clearly. “Hum of the Machinist’s Lover” is essentially cute, (“Eyes flicker // like flashlights are behind / them because flashlights are / behind them”) although it does dovetail nicely with the Detroit/machine theme. “Macrophobia” and “I Do Have a Seam” are the other obvious love poems in the collection, and both of them address a woman who is virtually invisible, assumed to be present. The emotion rings less true, or at least less accessible, than the feeling evoked in the poems on other subjects.

Is this a significant problem with the collection? I don’t find it so. Any number of people write lucid, believable love poems (probably everyone who makes it through their adolescence manages to write, or at least be capable of writing, a really good love poem once in their lives.) The gifts May has when he conveys the pain and rapture of the city and its machines, or when he gestures towards death, are at least as rich as conventional love poems and far more unique.

Also, although I have so thoroughly convinced myself of my correctness that I hardly feel the need to keep saying it, May’s work is further proof of the nonsensical distinction between academic and performance poetry. May’s command of language, his deliberateness, and his facility with form are impossible to ignore. And how was he driven to arrive at that level of mastery? How did he get through an MFA with the urgency and wildness and humanity of voice still intact? I would argue, through a background in performance and poetry slam. Language is a tool that May is using, not to make ornaments, but to externalize his reality, to give himself to the reader.

So here again, we find a mutual reliance, between craft and urgency, between voice and text, just as May finds “celebration in the convulsions,” the reliance between beauty and ugliness, between innocence and experience, between violence and – what? What really is the opposite of violence? To know, intimately, the inner life of what you had hurt. To long for peace, while knowing that peace is impossible.