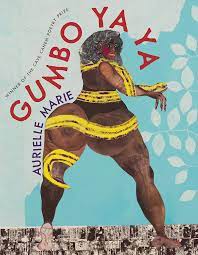

Gumbo Ya Ya by Aurielle Marie

Reviewed by francxs gufan nan

"the world is seldom mine / to build; but is indeed, here, ours"

Content warning for misogynoir, police violence

First, I acknowledge that this book wasn't written for me. The "we" of Aurielle Marie's debut collection of poems is, unapologetically, Black queer folks. As Marie shares in several interviews, one of their aims with Gumbo Ya Ya (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2021) was to write a book of poems that worldbuilds a safe space for queer Black femmes—regardless of any discomfort to anyone else who could be reading the book. Gumbo Ya Ya is for "urrbody wit an x," as Marie dedicates in one poem, and is a volume that resists the gaze of anyone not queer- and Black-identifying.

Written from a place of personal stakes, Marie's poems hold as truths the hard, gritty realities that Black queer folks face: both life-threatening violence and more everyday, insidious pressures to conform. Marie captures these multiplicitous harms in the following excerpt from the title poem, "gumbo ya ya," when describing the racial and gender divides at a Women's March:

at the pussy march, the women were bitches

my bitches marched, some without pussies

some of my bitches, ain't. just like that.

i, she-bitch, birthed megaphones

the women held their purses in the downbend

of their mouths— away from us, they kept their children & the keys to the city

their pussies fists, closed. their backs turned, refusing to meet our eyes.

all the names they shouted

was our names.

all the gxrls they chanted was our gxrls:

Mercedes Successful, Atattiana [sic], Mya, Sandra, Ayana Stanley's sweet seven year old body, Rekia Boyd and her skull-hole, Tanisha, Shelley Frey. Alexia Christian, her hands with more wounds than a certain messiah. Natasha McKenna, Tarika Wilson, Kayla Moore, Malissa Williams, Miriam Carey, we sang Shantel Davis like an aria, and Kendra James too. Duanna Johnson's we whispered like a secret and oh, our gxrls our gxrls our gxrls. our gxrls our gxrls our gxrls our gxrls. our gxrls. our gxrls. our gxrls. our gxrls. ours.

despite them singing us out like war songs they treated us like paupers

In this excerpt, and many others, Marie lays bare why Black gxrls and womxn—with the "x"—need a safe space of their own given the range of threats they face, even from women with an "e."

Specifically, Marie describes the ironic dynamics at a Women's March between non-queer women and the gender diverse people by the speaker's side. Despite the daytime marchers—who face no threat of police brutality in response to their gathering—chanting the names of Black women and (trans) womxn, they nonetheless treat the very same demographic in their midst with disdain and suspicion. Despite almost all of the names the women chant representing Black womxn murdered by police violence, many in police custody or in their own homes, the full scale of these tragedies seems lost on the women, who chant and march but mistreat the living and breathing Black folks before them.

Though Marie doesn't explicitly lay out the difference between those with an "e" and those with an "x," Marie's words and rhetorical choices signal their message for anyone who is ready to listen.

Take the first three lines of the excerpt, for instance. The words "pussy" or "pussies" and "bitches" repeat, connecting the lines sonically in a gradatio, a rhetorical device—known also as a marching figure of speech—where the last word of one clause becomes the first word of the next. But as the poem progresses, the meanings of the words shift. At the "pussy" march, a protest of the patriarchy, those without literal "pussies" are nonetheless ignored, even if they are also oppressed, creating an exclusion even at a march meant to empower. The speaker's "bitches" neither have pussies nor are bitchy in the same way as the women marchers. Despite the aural connection between the repeated words, Marie renders this connection superficial. By disrupting the first line with their second and third lines, Marie builds a gradatio that caves in on itself, just like the empty solidarity of the women marchers.

Alongside that othering, that all-too-familiar exclusion, there is nonetheless space carved out for the Black-centered mourning in the remainder of the excerpt. Marie hews this space by first drawing a stark contrast between the guarded, cagey women and Marie's speaker's community of Black and queer gxrls, using repetitions of "us" and "our" versus "they" and "their." And, toward the end of the excerpt, indented from the margins, Marie lists 16 names of Black girls, women, and womxn murdered by police violence, followed by 11 repetitions of "our gxrls," interrupted here and there by full stops. Together, these chants call upon the cleansing power of repetition, which Marie has said in multiple interviews is "the delicate thing that makes magic possible."

Songs and poetry have helped Marie survive their own share of painful violences. In 2014, as a community organizer in the wake of Ferguson protests following Mike Brown's murder, Marie was kidnapped by the police: the police handcuffed Marie & held them without charge in the back of a police wagon for over 10 hours, driving them around and beyond Atlanta city limits. To drown out the police officers' taunting & intimidating & threatening, Marie sang southern church hymns and old organizing songs, whispered recitations of Paul Laurence Dunbar poetry, and wrote new poems in their head, as they shared in an interview with emerald faith and a later Tweet thread. Surviving that traumatic incident, among many, Marie Tweeted, crystallized that, "The intersection was alive on my body. I was at the meeting place of all the intricate violences we [Black womxn] face."

So, in their poems as in their praxes, in Gumbo Ya Ya Marie sets out to embody the world and freedom they and other Black gxrls need. Marie once said, in an interview with Danez Smith and Franny Choi, that "I think poeming and organizing are both striving for the same thing. They’re trying to imagine and realize a world more radical and more free than the one we’re in. At least my poems and my organizing."

Marie's poems reflect inspirations from their organizing: like many a contemporary grassroots organizer, Gumbo Ya Ya starts the very first poem, "notes & acknowledgements," with a land acknowledgement that "the land / we stand on is stolen." The poem continues on for 8 pages, at first growing from an anaphora of "I acknowledge," and comprising the entirety of the book's first section. Throughout the first poem, the speaker makes clear their politics, acknowledging their own fallibility, their ulterior motives, and their rage, before ending on a verso page with a challenge to action smack dab in the center of the page:

[yes, you must

do somethin.

if not, then what is

the point?]

Divided by entirely black recto and then verso pages, each subsequent section of Gumbo Ya Ya is collected loosely by place. Part "i" is rooted in the streets on which Marie's speakers—including a persona poem from the perspective of Erica Garner—protest, battle police brutality, and grieve publicly. In part "ii," we learn of the speaker's childhood amidst intracommunity violence borne by patriarchal men, the suffocating bounds of religion, and the many wounds of gossiping kin. Part "iii" is also a single poem, "gumbo ya ya," which sings a chorus of voices from Black womxnhood. Drawing the poems to a close, part "iv" is a soup of themes from the preceding chapters, as well as a carving out of space and peace by imagining "somewhere, a heaven just for / Black gxrls."

Part of Marie's world-making manifests in the physicality of their poems—their appearance on the page, their sways & swellings & swarms within and beyond the margins of traditional typesetting.

Flip through the pages of Gumbo Ya Ya and you'll see text in neat rows, braided zigzags, and justified to create crisp edges with jagged left and right margins. You'll see kinked and curled lines, and words that stamp and layer and repeat, that enlarge and amplify and multiply.

As Marie shared in an interview with Layla Benitez-James, in the process of writing and publishing Gumbo Ya Ya, they realized that, in order to buck the same insidious pressures to conform that Black womxn fight every day, they needed to shed any loyalties to the conventional look of poems as well. "I felt constrained by the line, sanitized by the margins of the book, even. [Instead, the words] needed to swell, it needed to be physical. And so it was."

Even the gritty matte finish of Gumbo Ya Ya's cover—which "gives it that textured, sandy feel that is so much nicer than normal matte finishes," cover designer Alex Wolfe shared with me—calls to mind the many references Marie makes in their poems to dirt, earth, silt… the loam from which Marie builds their world. (Y'all, this book feels so good—different, but good-different—on a tactile level, to hold in your hands!)

Just as Marie's words spill beyond their impress, their sound is a bubbling of textures—most familiar to their intended audience—and of intersectional identities humming together, from the Black Vernacular English of a gxrl from Atlanta to the Gumbo of French patois mixed with Creole English. Throughout Gumbo Ya Ya, Marie blends the many voices of Black womxn, from chanting protests in the streets to the enchanting anaphora of hymnals—from private prayers to ancestors, to the thousand cuts of gossiping kin.

These many voices form the bedrock of Marie's poems, the "fine clayey" gumbo soil that is one of the many meanings of gumbo ya ya. In Marie's prologue, gumbo ya ya is both noun and verb, a "wild-making noise" of uncontainable joy or grief, "the soup of noise made by everyone talking at once," as well as:

gum∙bo ya∙ya n.

(/'gǝmbō/ \ yä'yä \) ∙ Creole-English origin.

[...]

4. A fine clayey soil that beomes sticky and impervious when wet, most notably under the nails of Black femmes.

[alternate spellings: gumbo yah∙yah, gum∙bo, gum∙beaux, black gxrl]

v. (/'gǝmbō/ \ yä'yä \)

1. Noise

a. To create from nothing

b. To survive at an intersection

c. And fight to be made visible.

Gumbo ya ya also means—as Marie cites in an epigraph from Madame Luisa Teish for the title poem "gumbo ya ya" —"a cacophony of sound, like a swarm of bees." As Marie interprets, in their illuminating interview with Alyshia Nicole Harris, "[Teish, in her book Jambalaya,] talked about gumbo ya ya as a sensorial experience, you know, the sound that takes over a room when family is getting together, that sort of buzzing humm that happens. And for me, it just stuck. It's like, 'Oh my God. That's like, the Blackest thing!'"

Amidst the many voices Marie stirs, there are also the silences. Line breaks, slashes, vertical bars, dashes and more capture the urgency and breath with which Black gxrls have to fight for humanization. As Marie once Tweeted, "There was many times, young as a bitch is, that were the almost end for me/the book. [...] It’s these lil almosts that break the line."

Together, the poems of Gumbo Ya Ya create a "hearty cauldron" of spells that remind us: we owe so much to Black womxn. Marie's poems, like their social justice praxes, are audacious, and unapologetic. Whereas the world outside Gumbo Ya Ya belittles and betrays Black womxn on the daily, in their poems Marie instead decenters anyone else's comfort. "The world is seldom mine / to build; but is indeed, here, ours," writes Marie, who hollows out the spaces of harm to conjure hallowed ground.

Frances Nan (francxs gufan nan) is almost 32 and an emerging poet. They get to wade through the slush pile as a reader at Frontier Poetry and have kicked it with other swell poets via fellowships from the Open Mouth Poetry Retreat, Brooklyn Poets, and The Watering Hole.