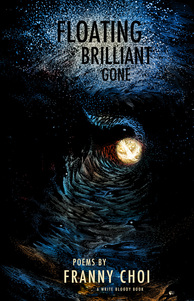

Floating, Brilliant, Gone by Franny Choi

A Review by Lindsay King-Miller, Book Reviewer

Franny Choi’s debut poetry collection Floating, Brilliant, Gone skillfully addresses trauma, identity, memory, and grief, positioning the poet as both witness to and evidence of loss, daring the past to blink first. Jess X. Chen’s illustrations – birds and bones, trees and feathers – highlight the uneasy ethereality that runs through the collection. Together, the words and images evoke the relationship between absence and permanence, a haunted house with windows opening onto surprising moments of beauty and joy.

The first poem in the book, “Notes on the Existence of Ghosts,” provides a lens through which to view the rest of the collection. “I understand the gravity of a train from the empty space and afterbirth air I encounter when I run down to the platform twenty seconds too late. It is the same with all things of such weight – to know them best when you have just missed them,” Choi writes. Throughout Floating, Brilliant, Gone, this concept resonates and echoes: the memory or perception of something being more real than the thing itself.

This is not, however, to say that Choi’s poems are primarily cerebral or abstract. She goes on to write, “If the stars have, as they say, been dead for millions of years by the time their light reaches us, then it follows that my retinas are a truer thing to call sky.” In these poems, a body is the story of everything that has happened to it, everything it has experienced. Memory itself is physical. In “The Well,” Choi writes, “She marries the dust. / The dust is a boy who fell. / A boy is like a memory / but heavier.” There is little difference here between an object and the residue it leaves – the reader can feel the weight, the texture of the dust. Loss is tangible and ongoing, constantly present in the body.

The specific loss that permeates Floating, Brilliant, Gone is named in “Halloween, 2009”:

When my boyfriend’s mother

called to tell me

he was dead

I called her a liar

However, Choi makes the bold choice to write about the death of a lover while seldom directly discussing love. Emotion, like death, is best understood by the traces it leaves behind. Neither does the collection deal explicitly with the grieving process. Instead, the poet focuses on moments and images, objects that create ripples far beyond themselves. In “Annie Mason’s Collie,” she writes:

I’ve never seen death

streak across the sky

of a loved one’s face –

just mapped out the craters it leaves

In a collection about loss and embodiment, the physical body of the poet is always necessarily present, like the ghosts Choi summons so eloquently. The body is not an abstraction; Choi’s identity as a Korean-American woman informs many of the pieces in Floating, Brilliant, Gone. As with ghosts and memories, the body here stands for something larger than itself: race, identity, lineage, sex, touch. In “To the Man who Shouted ‘I Like Pork Fried Rice’ at Me on the Street,” the speaker fights back against the commodification, the implied consumption, of her body, imagining herself as edible but vicious, “squirming alive / in your mouth / strangling you quiet / from the inside out.” The painful knowledge of racism and misogyny is an undercurrent throughout the collection, another kind of remnant – the shadow an objectifying culture leaves on its survivors. “Be lined / with teeth – anything / but soft,” Choi writes in “How to Get Home Safely.” This fear is also a ghost, a mark on the body left by dire possibility.

Although formal innovation is not a driving force in Floating, Brilliant, Gone, largely taking a backseat to narrative and image, there are moments throughout the collection where Choi experiments with form to powerful effect. The handwritten flow-chart shape of “Never Here,” which provides multiple paths to the same final stanza, is one of the most memorable pieces in the book, as is the erasure poem “Native Language,” where Choi writes “broken fossil / story / I inherited / jumbled / text” between blocks of blacked-out and unknowable words. Here, the negative space defining what it reveals, present as a concept throughout the entirety of the book, is physically present on the page.

Throughout, Choi’s language is sparse while still managing to surprise with neat twists and unexpected juxtapositions. The last lines of a poem are often the most important – they’re where the truth of the poem is revealed, or something unexpected happens, or simply the lines that ring the longest in the reader’s ears – and Choi’s endings shine, summing up the intention of the poem without being too obvious or pedantic. In “Bird Watching,” Choi writes about damage and trauma, another extension of the interplay between loss and body – the physical scars, and the fetishization of a woman’s suffering. She ends here:

Everyone wants

a broken-glass girl,

bought secondhand.

Look. The damage

was already there.

Choi concludes poems like a gymnast sticking a difficult move, with force as well as flourish. In “Too Many Truths,” Choi articulates what could be the moral of the whole collection, a history of a body interacting with other bodies, of breaking things and losing things, ending with “Body spills all the light. Body / all the light. Body only dark / when it wants to be.” Depending on the reader’s mood, this could be a daily affirmation or a battle cry. Either way, it’s lovely.

Unlike many poetry collections dealing with trauma and sorrow, Floating, Brilliant, Gone is not an anthem to overcoming. In “How to Win an Argument,” the speaker describes not debating but leaving: “When he laughs at the texture of your sadness, / turn away from his mouth, no matter how soft.” There is no victory here, only escape. This is a book about carrying impossible weight, and Choi does not pretend it’s easy, or even possible, to shrug off that weight and keep moving. The optimism in these poems is fragile and quiet. “My lover who is here / is here,” she writes. “And / that’s the first and last reason.”