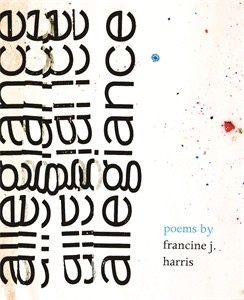

allegiance by francine j. harris

Reviewed by Corrina Bain, Book Reviewer

What is a poem supposed to do? Of course there’s no singular answer to that question. Writers work toward different goals. But in workshops, in editing, often we ask, Does this poem do what I want? Does it make sense? So, it is with some trepidation that I will be misunderstood when I say about francine j. harris’s book: allegiance often does not make sense. It succeeds, however, in doing many other things.

allegiance touches on universal thematic areas – sexuality, brutality, faith, race – and yet francine j. harris’s vision is so specific that the concepts are rendered unique each time. This new perspective on the familiar can be disorienting. How can I interpret, for example, a book which is certainly shaped by the sociocultural location of a Black, Detroit-native speaker, which never offers me a racial polemic? How to face the fiercely embodied yet ambivalent female sexuality of a poem like fume: “love is a rage that never quite slaughters. a murder with no body. a lighthouse sinking invisible ships. a robber with no hands. // a rapist alone”? And then there is the fact that, in some poems, there is an element of narrative that I cannot follow. How to handle the span of emotion, combined with my uneven comprehension of what is being presented? When I facilitate workshops, I often tell participants that poems are not made to be understood in a singular way, and that every reading is valid. Yet, in reading allegiance, I was frequently beset by the feeling that there was something happening beyond the reach of my intelligence. So, I did the most intelligent thing I could: I asked someone.

I asked Jamaal May, a stunning writer and Detroit native who was partly responsible for my awareness of francine j. harris. I initially came across one of her poems in Rattle and held a dim awareness in the back of my brain that this person, at some point, was bound to write a book. I saw that same gorgeous poem while working with Jamaal on a slam team last summer. Of the entire packet of contemporary poems Jamaal had brought for the group, francine j. harris’s piece sparked the most conversation and produced the most work. So I intuited, partly because of his familiarity with the author’s work and setting, and partly because he thinks about poems like it is his job, that Jamaal May could help me feel less benighted by allegiance. Many of the more intelligible bits of the following paragraphs are rooted in Jamaal’s explications.

Our conversation began with my questions about accessibility. While the approach to narrative is often elliptical, the poems are written in common, plainspoken language. When the reader is challenged to construct meaning, it is more a question of interpreting the image rather than word choice. She is at once inviting the reader in and giving them work to do. She avoids melodrama by making the reader complete the action of the poem, leading to a meaning or conclusion that feels all your own. It creates a close, often uncomfortable intimacy between the reader and the text. In the remarkable list poem what you’d find buried in the dirt under charles f. kettering sr. high school, the objects tell a multiplicity of stories, reflecting not just the various lives that pass through the physical space, but the infinite perspectives brought by each reader into the poem.

Another technique allegiance employs is the use of a negative to frame what remains, as in the opening poem, sift: “i am not all river / not the sand on the tongue’s first someone” or in the ghazal i live in detroit, which both names and refutes the beauty in the urban pastoral, “there are plenty of violets in flophouses… the city spits iris and scratches the back of your throat in detroit.” This definition through negation relates in part to the speaker’s minority status, (as it always does: a woman is a not-man, a Black person is a not-white), but it also taps into an essential separateness, the isolation of each individual in their skin, the sense of being the observer no matter how affected by the story you may be. One of the triumphs of katherine is how the speaker’s brutality gives form to tenderness, illustrating how an emotion, subjected to enough scrutiny, usually contains its opposite.

Early in our conversation, Jamaal said “francine actually is experimental, and a poet, not experimental, like when most people say it and mean ‘wack shit that I can intellectualize is good.’” Her unconventional use of space on the page, syntax, and avoidance of capital letters all have the effect of making the reader re-learn how to interact with the poem. Yet the experiment is not pretentious or obtuse. If anything, these eccentric grammar and punctuation techniques have the effect of restoring written language to something like actual speech, fragmented and reliant on context. The way, again in katherine, the syntactically odd but intact refrain of the title gives way, by the end, to “Katherine the lazy short./not a good poet. and shit.” Even on the level of line and stanza, allegiance offers intelligent variation, juxtaposing blockier, dense bits of almost-prose with pieces that are more sparse on the page and delicate in their enjambment.

Overall, the unevenness of my understanding of the book does make me yearn for an entire volume of poems like the ones that I think I “get.” However, the structure of the book in its entirety is deeply satisfying. When I say that there are “themes” in allegiance, I actually mean it. Concepts that trouble or entrance the speaker come back restructured, relit, giving the reader a deeper experience. It is clear, in reading allegiance, that francine j.harris is a writer of exceptional style and thrilling vision. I think it is somewhat emblematic that in order to feel like I had written a review that did the book justice, I had to talk to Jamaal: francine j. harris gives the reader a rare gift, a discomfort that provokes you to connect.

allegiance touches on universal thematic areas – sexuality, brutality, faith, race – and yet francine j. harris’s vision is so specific that the concepts are rendered unique each time. This new perspective on the familiar can be disorienting. How can I interpret, for example, a book which is certainly shaped by the sociocultural location of a Black, Detroit-native speaker, which never offers me a racial polemic? How to face the fiercely embodied yet ambivalent female sexuality of a poem like fume: “love is a rage that never quite slaughters. a murder with no body. a lighthouse sinking invisible ships. a robber with no hands. // a rapist alone”? And then there is the fact that, in some poems, there is an element of narrative that I cannot follow. How to handle the span of emotion, combined with my uneven comprehension of what is being presented? When I facilitate workshops, I often tell participants that poems are not made to be understood in a singular way, and that every reading is valid. Yet, in reading allegiance, I was frequently beset by the feeling that there was something happening beyond the reach of my intelligence. So, I did the most intelligent thing I could: I asked someone.

I asked Jamaal May, a stunning writer and Detroit native who was partly responsible for my awareness of francine j. harris. I initially came across one of her poems in Rattle and held a dim awareness in the back of my brain that this person, at some point, was bound to write a book. I saw that same gorgeous poem while working with Jamaal on a slam team last summer. Of the entire packet of contemporary poems Jamaal had brought for the group, francine j. harris’s piece sparked the most conversation and produced the most work. So I intuited, partly because of his familiarity with the author’s work and setting, and partly because he thinks about poems like it is his job, that Jamaal May could help me feel less benighted by allegiance. Many of the more intelligible bits of the following paragraphs are rooted in Jamaal’s explications.

Our conversation began with my questions about accessibility. While the approach to narrative is often elliptical, the poems are written in common, plainspoken language. When the reader is challenged to construct meaning, it is more a question of interpreting the image rather than word choice. She is at once inviting the reader in and giving them work to do. She avoids melodrama by making the reader complete the action of the poem, leading to a meaning or conclusion that feels all your own. It creates a close, often uncomfortable intimacy between the reader and the text. In the remarkable list poem what you’d find buried in the dirt under charles f. kettering sr. high school, the objects tell a multiplicity of stories, reflecting not just the various lives that pass through the physical space, but the infinite perspectives brought by each reader into the poem.

Another technique allegiance employs is the use of a negative to frame what remains, as in the opening poem, sift: “i am not all river / not the sand on the tongue’s first someone” or in the ghazal i live in detroit, which both names and refutes the beauty in the urban pastoral, “there are plenty of violets in flophouses… the city spits iris and scratches the back of your throat in detroit.” This definition through negation relates in part to the speaker’s minority status, (as it always does: a woman is a not-man, a Black person is a not-white), but it also taps into an essential separateness, the isolation of each individual in their skin, the sense of being the observer no matter how affected by the story you may be. One of the triumphs of katherine is how the speaker’s brutality gives form to tenderness, illustrating how an emotion, subjected to enough scrutiny, usually contains its opposite.

Early in our conversation, Jamaal said “francine actually is experimental, and a poet, not experimental, like when most people say it and mean ‘wack shit that I can intellectualize is good.’” Her unconventional use of space on the page, syntax, and avoidance of capital letters all have the effect of making the reader re-learn how to interact with the poem. Yet the experiment is not pretentious or obtuse. If anything, these eccentric grammar and punctuation techniques have the effect of restoring written language to something like actual speech, fragmented and reliant on context. The way, again in katherine, the syntactically odd but intact refrain of the title gives way, by the end, to “Katherine the lazy short./not a good poet. and shit.” Even on the level of line and stanza, allegiance offers intelligent variation, juxtaposing blockier, dense bits of almost-prose with pieces that are more sparse on the page and delicate in their enjambment.

Overall, the unevenness of my understanding of the book does make me yearn for an entire volume of poems like the ones that I think I “get.” However, the structure of the book in its entirety is deeply satisfying. When I say that there are “themes” in allegiance, I actually mean it. Concepts that trouble or entrance the speaker come back restructured, relit, giving the reader a deeper experience. It is clear, in reading allegiance, that francine j.harris is a writer of exceptional style and thrilling vision. I think it is somewhat emblematic that in order to feel like I had written a review that did the book justice, I had to talk to Jamaal: francine j. harris gives the reader a rare gift, a discomfort that provokes you to connect.