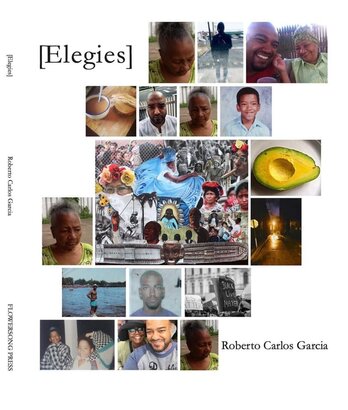

[Elegies] by Roberto Carlos Garcia

Reviewed by C. Bain

… this is how I want to know

love—through the gentle pain of experience,

because birds never ask is this song rivers

never ask is the ocean this way.

-“A Love Poem Post Love”

The work of grief is not simple, or small, or individual. It is one of the inarguable services poets perform. We help readers navigate grief, voicing what is beyond the purview of language or even thought, so that others, in the face of grief, can have some sort of orientation, some knowledge that they are in a space that’s shared. This is much, but not all, of the project of Roberto Carlos Garcia’s [Elegies], a collection anchored by a series of reflections on the meaning and beauty of his grandmother’s life.

This collection has a remarkably expansive voice, much of it resolutely accessible, even pedestrian, devoted to the acts of care and holding that happen in close “dysfunctional but happy” families—we see the speaker buying Kotex for his older sister in one poem, in another eating weed after seeing a police car drive by and then being too high to use a fork normally, much to another sister’s delight. From these easeful and joyous descriptions of care and family, the collection turns sharply on a brief essay entitled “10 Minutes of Terror,” a granular description of the speaker’s thoughts, as a man of color, being pulled over by police on the street that runs through the college campus where he works. At the same time that the speaker’s terror is activated, the intelligence and knowledge of his own context is luminous:

I am convinced that the terror the state wants us to feel, that the law enforcement officers who summarily execute BIPOC in this country want us to feel, that the Klan and all of their affiliates (many of whom have infiltrated state and law enforcement agencies) want us to feel, is the same terror they harbor of Us inside the nebulous psyche of whiteness… All I kept thinking was that I sat in that car alone and nobody knew I was there. That if he shot me dead there would be no witness…With each passing day it feels like there are more people on the side of this madness than people who would see it end.

After the essay’s tight marriage of emotion and political analysis, the tone shifts into an intensely lyric mythological imagining of the poet’s parents as Sea and Sky deities, using the archetypal images to illustrate, rather than erase, their passion and flawed humanity. At one point the sailor-sea god and the sky-mother descend in human form and dance in a nightclub:

The sailor and the sky owned the city & all in it,

owned each other. To own a thing tests your love of a thing

which is to say that for my father & mother

it would never be enough. They needed ruin.

- “A Tempest"

Just in those first thirty-something pages of the collection, we see that the poet operates on a field which spans a masterful tonal and emotional range. But more than merely demonstrating his facility with these different registers, it becomes clear over the course of the collection that the mythic and the more representational poems rely and build upon each other. The mythologies are a way of making sense in the face of terror, the familial love is what sustains and binds the poet to the world.

This expansive range is also applied to the elegiac project that is the core of the book, poems for the speaker’s grandmother Mami, a figure of care from the poet’s childhood. The opening poem shows Mami killing cockroaches with sky-blue plastic slippers. We see her in ordinary life, dancing in the kitchen, in cognitive decline, evoked in oratory as a spirit, calling to the poet from the other world, across the ten explicitly named elegies for Altagracia and also glimmering through other poems in the book. As an example of the celebration of the everyday, in “Elegy in which is hidden an ode to your beehive updo,” the speaker contemplates a photograph of Mami in the 1960s, shortly after immigrating:

… I don’t know the appeal of a beehive updo

except that you look so beautiful, so confident, so like me when

I’m wearing new sneakers & starting out in the evening

This tender, literal treatment of Mami, in the mundane but cherished photographic image, sets up for another turn: The speaker plunges into a metaphysical space two pages later, reflecting on Mami’s death in “Elegy in which I recall being told you were dying”:

… staring like a fool into the blue silk of night’s skirt

while the loom making life’s fine muslin broke

& the moon offered only the cold silver of struggle.

Again, the different imageries and scales of grief, from reminiscing over a hairdo in a photograph, to feeling the fabric of life unseam, begins to map the perimeter of the uncaptureable reality of grief.

In these elegies for the speaker’s grandmother, which often function like letters to the departed, Garcia explores the complexity of holding a private grief in a world that constantly produces public, political atrocity. Although elegiac work is in a sense always political (Who gets to have their death recognized as an event in America? Who gets to be mourned?), poems with titles like “Elegy in which I hide an elegy in a ghazal for Syria” or “Elegy in which I explain the end of the world to a ghost” show us the connective possibilities of grief, the paradox of the isolated feeling-state that is a horrible but unifying thread to the outside world.

The transcendental, mythologizing themes in this book give us a clue, that time is cyclic, that part of living is becoming an ancestor. Towards the end of the book, the circular nature of time is made explicit in “Variation on Lines of Dialogue from Bill Murray’s Groundhog Day,” with the laugh-line “I know what you’re thinking—Groundhog Day is a comedy / & this poem sounds like your favorite rapper’s first album,” punctuating the juxtaposition of filmically looped time and generational cycles of poverty and capitalist exertion. The cyclic nature of time is elsewhere evoked in relation to the media cycles of Black death, as well as the static, endless yet also timeless quality of grief itself.

In a year, (stretching into years,) when the collective trauma is unnavigable, we need books like [Elegies]; we need instructions on how to mourn and proof that others have been there.

love—through the gentle pain of experience,

because birds never ask is this song rivers

never ask is the ocean this way.

-“A Love Poem Post Love”

The work of grief is not simple, or small, or individual. It is one of the inarguable services poets perform. We help readers navigate grief, voicing what is beyond the purview of language or even thought, so that others, in the face of grief, can have some sort of orientation, some knowledge that they are in a space that’s shared. This is much, but not all, of the project of Roberto Carlos Garcia’s [Elegies], a collection anchored by a series of reflections on the meaning and beauty of his grandmother’s life.

This collection has a remarkably expansive voice, much of it resolutely accessible, even pedestrian, devoted to the acts of care and holding that happen in close “dysfunctional but happy” families—we see the speaker buying Kotex for his older sister in one poem, in another eating weed after seeing a police car drive by and then being too high to use a fork normally, much to another sister’s delight. From these easeful and joyous descriptions of care and family, the collection turns sharply on a brief essay entitled “10 Minutes of Terror,” a granular description of the speaker’s thoughts, as a man of color, being pulled over by police on the street that runs through the college campus where he works. At the same time that the speaker’s terror is activated, the intelligence and knowledge of his own context is luminous:

I am convinced that the terror the state wants us to feel, that the law enforcement officers who summarily execute BIPOC in this country want us to feel, that the Klan and all of their affiliates (many of whom have infiltrated state and law enforcement agencies) want us to feel, is the same terror they harbor of Us inside the nebulous psyche of whiteness… All I kept thinking was that I sat in that car alone and nobody knew I was there. That if he shot me dead there would be no witness…With each passing day it feels like there are more people on the side of this madness than people who would see it end.

After the essay’s tight marriage of emotion and political analysis, the tone shifts into an intensely lyric mythological imagining of the poet’s parents as Sea and Sky deities, using the archetypal images to illustrate, rather than erase, their passion and flawed humanity. At one point the sailor-sea god and the sky-mother descend in human form and dance in a nightclub:

The sailor and the sky owned the city & all in it,

owned each other. To own a thing tests your love of a thing

which is to say that for my father & mother

it would never be enough. They needed ruin.

- “A Tempest"

Just in those first thirty-something pages of the collection, we see that the poet operates on a field which spans a masterful tonal and emotional range. But more than merely demonstrating his facility with these different registers, it becomes clear over the course of the collection that the mythic and the more representational poems rely and build upon each other. The mythologies are a way of making sense in the face of terror, the familial love is what sustains and binds the poet to the world.

This expansive range is also applied to the elegiac project that is the core of the book, poems for the speaker’s grandmother Mami, a figure of care from the poet’s childhood. The opening poem shows Mami killing cockroaches with sky-blue plastic slippers. We see her in ordinary life, dancing in the kitchen, in cognitive decline, evoked in oratory as a spirit, calling to the poet from the other world, across the ten explicitly named elegies for Altagracia and also glimmering through other poems in the book. As an example of the celebration of the everyday, in “Elegy in which is hidden an ode to your beehive updo,” the speaker contemplates a photograph of Mami in the 1960s, shortly after immigrating:

… I don’t know the appeal of a beehive updo

except that you look so beautiful, so confident, so like me when

I’m wearing new sneakers & starting out in the evening

This tender, literal treatment of Mami, in the mundane but cherished photographic image, sets up for another turn: The speaker plunges into a metaphysical space two pages later, reflecting on Mami’s death in “Elegy in which I recall being told you were dying”:

… staring like a fool into the blue silk of night’s skirt

while the loom making life’s fine muslin broke

& the moon offered only the cold silver of struggle.

Again, the different imageries and scales of grief, from reminiscing over a hairdo in a photograph, to feeling the fabric of life unseam, begins to map the perimeter of the uncaptureable reality of grief.

In these elegies for the speaker’s grandmother, which often function like letters to the departed, Garcia explores the complexity of holding a private grief in a world that constantly produces public, political atrocity. Although elegiac work is in a sense always political (Who gets to have their death recognized as an event in America? Who gets to be mourned?), poems with titles like “Elegy in which I hide an elegy in a ghazal for Syria” or “Elegy in which I explain the end of the world to a ghost” show us the connective possibilities of grief, the paradox of the isolated feeling-state that is a horrible but unifying thread to the outside world.

The transcendental, mythologizing themes in this book give us a clue, that time is cyclic, that part of living is becoming an ancestor. Towards the end of the book, the circular nature of time is made explicit in “Variation on Lines of Dialogue from Bill Murray’s Groundhog Day,” with the laugh-line “I know what you’re thinking—Groundhog Day is a comedy / & this poem sounds like your favorite rapper’s first album,” punctuating the juxtaposition of filmically looped time and generational cycles of poverty and capitalist exertion. The cyclic nature of time is elsewhere evoked in relation to the media cycles of Black death, as well as the static, endless yet also timeless quality of grief itself.

In a year, (stretching into years,) when the collective trauma is unnavigable, we need books like [Elegies]; we need instructions on how to mourn and proof that others have been there.

C. Bain is a gender liminal artist based in Brooklyn. His book, Debridement, was a finalist for the Publishing Triangle awards. His writing is published in journals and anthologies such as BOAAT, them., Bedfellows Magazine, PANK, and elsewhere. His plays have been performed at Dixon Place, The Kraine, and The Tank in NYC. He is a performer, and has worked as an actor with several independent theater companies. He apprentices at Ugly Duckling Presse, and is a Lambda Literary fellow. He works extensively with trauma, embodiment, and sexuality, but he’d rather just dance with you. More at tiresiasprojekt.com