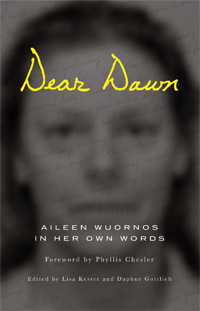

Dear Dawn: Aileen Wuornos in Her Own Words

Edited by Daphne Gottlieb and Lisa Kester

Reviewed by Lindsay King-Miller, Book Reviewer

You've probably already heard of Aileen Wuornos. Frequently (and erroneously) described as “the first female serial killer,” she murdered seven men in 1989 and 1990 while hooking and hitchhiking on the Florida highways. Wuornos was later convicted of six counts of murder and sentenced to death six times. (Though she confessed to seven murders, the seventh victim's body was never found.) On October 9, 2002, she was executed by lethal injection in Florida. Charlize Theron played her in a movie. For a while after her arrest, feminists embraces Wuornos as a kind of icon; her plea that she killed in self-defense serving as a rallying cry for sex workers and abused women. Today, however, she is largely forgotten by feminists who have moved on to more palatable heroes.

While on death row, Wuornos wrote letters – usually daily, often several in one day – to her childhood friend Dawn Botkin. She reminisced about old times, talked about her favorite musicians, and quoted the Bible at length; she discussed her murders and described how she believed the prison guards were conspiring to torture her. Dear Dawn, edited by Daphne Gottlieb and Lisa Kester, condenses ten years of obsessive correspondence into a fragmented, sometimes funny, sometimes nightmarish, often paradoxical portrait of Wuornos in her final years.

Lee, as Wuornos signs all her letters, dropped out of school early, and her correspondence reveals her lack of education. Spelling and punctuation are haphazard, grammar scattershot. The inconsistency of the writing also echoes the instability of the mind behind it: “. . . . i’m having so much difficulty then – ANY OTHER INMATE HERE... UNREAL!. So I’m in blind fury . . . I need to take a 'PolyGRAPH ON ALL OF tHis., , EXTREMELY SERIOUS SHIT! HAVE TOO!.'” Upon first opening the book, a reader may find the letters alienating or idiosyncratic to the point of incomprehensibility. However, it becomes all too easy to slip through the barrier into Lee's strange, off-kilter world; finding the way back into real life is like swimming through murky water. The strangeness of the prose acts as a sort of membrane, difficult to penetrate from either direction – at first it's hard to get in, then it's hard to get out.

Lee vacillates so wildly and changes her mind so suddenly that seeing the world through her eyes can be profoundly disorienting. At times, she describes herself as an avenging angel for battered women, asserting that her punishment is unjust “[b]ecause women arent suppose to pose such power and authority over themselves against an assailant. where suppose to be abused, used, raped, and beaten, and then call the cops afterward . . . Actually I should be given a metal for it.” Elsewhere, she shows remorse, blaming the murders on forces beyond her control: “I became possessed in the force of heavy Beer drinkin and bad experiences to recollect while under the curse’s of alcoholism. All so Sad. But true. The real Aileen never killed anyone.” But as her execution draws nearer, she recants her plea of self-defense and claims that she killed all seven men for what was in their wallets. With a strange air of nostalgia, Lee writes, “While I thumbed an hooked, we were left in another financial upset, and with the rain still coming down hard. Robbed Then and Killed 7.” Anyone reading Dear Dawn hoping to encounter the true story of Wuornos's murders will be disappointed. It's easy to imagine that even Lee herself wasn't sure why she killed those seven men – or at least, that her convictions shifted from day to day.

Wuornos is every bit as capricious in her relationships with living friends and family. Her adopted mother Arlene Pralle is subject to the some of her most intense volatility. In one letter, Arlene is “a warm hearted 'Christian freak' that just Loves to help people.” In another, Lee writes, “Arlene is lieing through her teeth . . .And now I know for a 'fact' she is full of shit!” At one point, Lee becomes convinced that Arlene has mob connections and is trying to have her murdered. The deeper the reader travels into Lee's world, the more challenging it becomes to separate insight from paranoia. She has, indeed, been shamefully mistreated, and she does, indeed, frequently imagine that she is being mistreated. How can an observer know where to draw the line?

As the date of her execution draws nearer, Lee's tenuous connection to reality becomes ever more unstable. She believes the prison guards are spitting in and poisoning her food. Her relationship to Christianity, always intense, becomes increasingly bizarre, and she frequently expresses it through Star Trek analogies: “The Bridge aboard the starship. Switching it around to 'The Throne', and instead of Kirk or Picard in Control . . . Its Jesus.” Far from clinging to life, as far as Lee is concerned, her lethal injection can't arrive soon enough. “I’ll miss you Dawn. And a few others! But I HATE this world. I’d perferr to leave it.”

Despite that hatred, which is always close to the surface, Lee shows surprising depths of love: for the cats she used to have, for ex-lover Tyria Moore, for her deceased brother Keith, for her few happy memories of childhood, and most of all for Dawn. “That’s Just the way I am,” she writes. “I Love to give Love . . . I know I’ve hurt, myself over being this away. But the pain, doesn’t feel, so bad, when you know your struggling to give love, for a cause that really pays off.”

Just as it is difficult to categorize Lee – madwoman or martyr, innocent driven to extremes or cynical, opportunistic killer – so Dear Dawn defies easy labels. It isn't a true-crime story of the type we're familiar with. It doesn't explain or justify the murders, and it's far too fractured and unreliable to serve as a traditional memoir. In fact, with its fragmented language and unexpected juxtapositions, the literary genre it resembles most may be poetry. Though Lee doesn't have a poet's control of language, the sheer exuberance of her writing reveals layers of complicated, often contradictory meaning.

There are no easy answers in Dear Dawn. The hints of light and laughter in Wuornos's writing don't obscure the darkness, the paranoia, the violence. Being a victim doesn't make her less of a villain; her kindness doesn't cancel out her crimes. But as the reader grows intimately acquainted with her best and worst qualities, it's hard to avoid feeling guilty affection for Lee. She is the friend who you know is bad news, but you just can't tear yourself away. She offers so little in the way of explanation or even self-awareness, yet you feel as though you know her as well as she knows herself, and that kind of familiarity is, perhaps, not too far removed from love.

“Anyway buddy,” she writes, “I know you’ll stick beside me to thee end. And I Love you dearly Dawn . . . My only true friend.”

While on death row, Wuornos wrote letters – usually daily, often several in one day – to her childhood friend Dawn Botkin. She reminisced about old times, talked about her favorite musicians, and quoted the Bible at length; she discussed her murders and described how she believed the prison guards were conspiring to torture her. Dear Dawn, edited by Daphne Gottlieb and Lisa Kester, condenses ten years of obsessive correspondence into a fragmented, sometimes funny, sometimes nightmarish, often paradoxical portrait of Wuornos in her final years.

Lee, as Wuornos signs all her letters, dropped out of school early, and her correspondence reveals her lack of education. Spelling and punctuation are haphazard, grammar scattershot. The inconsistency of the writing also echoes the instability of the mind behind it: “. . . . i’m having so much difficulty then – ANY OTHER INMATE HERE... UNREAL!. So I’m in blind fury . . . I need to take a 'PolyGRAPH ON ALL OF tHis., , EXTREMELY SERIOUS SHIT! HAVE TOO!.'” Upon first opening the book, a reader may find the letters alienating or idiosyncratic to the point of incomprehensibility. However, it becomes all too easy to slip through the barrier into Lee's strange, off-kilter world; finding the way back into real life is like swimming through murky water. The strangeness of the prose acts as a sort of membrane, difficult to penetrate from either direction – at first it's hard to get in, then it's hard to get out.

Lee vacillates so wildly and changes her mind so suddenly that seeing the world through her eyes can be profoundly disorienting. At times, she describes herself as an avenging angel for battered women, asserting that her punishment is unjust “[b]ecause women arent suppose to pose such power and authority over themselves against an assailant. where suppose to be abused, used, raped, and beaten, and then call the cops afterward . . . Actually I should be given a metal for it.” Elsewhere, she shows remorse, blaming the murders on forces beyond her control: “I became possessed in the force of heavy Beer drinkin and bad experiences to recollect while under the curse’s of alcoholism. All so Sad. But true. The real Aileen never killed anyone.” But as her execution draws nearer, she recants her plea of self-defense and claims that she killed all seven men for what was in their wallets. With a strange air of nostalgia, Lee writes, “While I thumbed an hooked, we were left in another financial upset, and with the rain still coming down hard. Robbed Then and Killed 7.” Anyone reading Dear Dawn hoping to encounter the true story of Wuornos's murders will be disappointed. It's easy to imagine that even Lee herself wasn't sure why she killed those seven men – or at least, that her convictions shifted from day to day.

Wuornos is every bit as capricious in her relationships with living friends and family. Her adopted mother Arlene Pralle is subject to the some of her most intense volatility. In one letter, Arlene is “a warm hearted 'Christian freak' that just Loves to help people.” In another, Lee writes, “Arlene is lieing through her teeth . . .And now I know for a 'fact' she is full of shit!” At one point, Lee becomes convinced that Arlene has mob connections and is trying to have her murdered. The deeper the reader travels into Lee's world, the more challenging it becomes to separate insight from paranoia. She has, indeed, been shamefully mistreated, and she does, indeed, frequently imagine that she is being mistreated. How can an observer know where to draw the line?

As the date of her execution draws nearer, Lee's tenuous connection to reality becomes ever more unstable. She believes the prison guards are spitting in and poisoning her food. Her relationship to Christianity, always intense, becomes increasingly bizarre, and she frequently expresses it through Star Trek analogies: “The Bridge aboard the starship. Switching it around to 'The Throne', and instead of Kirk or Picard in Control . . . Its Jesus.” Far from clinging to life, as far as Lee is concerned, her lethal injection can't arrive soon enough. “I’ll miss you Dawn. And a few others! But I HATE this world. I’d perferr to leave it.”

Despite that hatred, which is always close to the surface, Lee shows surprising depths of love: for the cats she used to have, for ex-lover Tyria Moore, for her deceased brother Keith, for her few happy memories of childhood, and most of all for Dawn. “That’s Just the way I am,” she writes. “I Love to give Love . . . I know I’ve hurt, myself over being this away. But the pain, doesn’t feel, so bad, when you know your struggling to give love, for a cause that really pays off.”

Just as it is difficult to categorize Lee – madwoman or martyr, innocent driven to extremes or cynical, opportunistic killer – so Dear Dawn defies easy labels. It isn't a true-crime story of the type we're familiar with. It doesn't explain or justify the murders, and it's far too fractured and unreliable to serve as a traditional memoir. In fact, with its fragmented language and unexpected juxtapositions, the literary genre it resembles most may be poetry. Though Lee doesn't have a poet's control of language, the sheer exuberance of her writing reveals layers of complicated, often contradictory meaning.

There are no easy answers in Dear Dawn. The hints of light and laughter in Wuornos's writing don't obscure the darkness, the paranoia, the violence. Being a victim doesn't make her less of a villain; her kindness doesn't cancel out her crimes. But as the reader grows intimately acquainted with her best and worst qualities, it's hard to avoid feeling guilty affection for Lee. She is the friend who you know is bad news, but you just can't tear yourself away. She offers so little in the way of explanation or even self-awareness, yet you feel as though you know her as well as she knows herself, and that kind of familiarity is, perhaps, not too far removed from love.

“Anyway buddy,” she writes, “I know you’ll stick beside me to thee end. And I Love you dearly Dawn . . . My only true friend.”