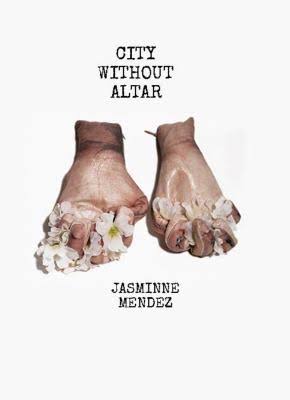

City Without Altar by Jasminne Mendez

Reviewed by Deborah D.E.E.P Moulton

“A part of me is searching for who, what we have left behind.” – Jasminne Mendez

For those of us who struggle with holding more than one marginalized identity, there is sometimes an impeding desire to choose one over the other. For example, the social need to label oneself forces us to decide on how the world will interact with us. However, there is a risk in removing one portion of oneself to save the other identity. There are casualties to every war, even one we fight with ourselves. This pull to find a neutral ground with one’s own identity is the guiding conflict that Jasminne Mendez wrestles with in her newest collection City Without Altar (Noemi Press, 2022).

Mendez is a Dominican-American poet, playwright, translator, and award-winning author of multiple books including Island of Dreams (Floricanto Press), Night-Blooming Jasmin(n)e: Personal Essays and Poetry (Arte Público Press), Islands Apart: Becoming Dominican American (Arte Público Press), and Josefina’s Habichuelas (Arte Público Press). This Cantomundo fellow and co-founder of the Houston based Latine literary arts organization, Tintero Projects, has dedicated her work to elevating Latine voices across the world. Identifying as Black, Latine, Disabled, and a Mother, Mendez's collection seeks to balance identities like no other. Finding parallels with the mutilation of the 1937 Haitian Massacre, Mendez examines her struggles with pregnancy, autoimmunity, and belonging. The collection is broken into three sections, consisting of prose and poems that flank either side of an interactive theatrical script. Readers are offered x-rays of Mendez’s hands throughout multiple medical procedures, interlaced around reports of General Trujilio “chopping” Haitians to death at the Dominican border. In addition, Mendez curates plot maps, lists, and fill-in-the-blanks to engage readers in the process of creating meaning from her text. She beckons readers to “lift up their names until someone else can hear it”.

The first section of the collection centers on omission. Opening with a black out poem created from Mendez’s birth certificate, readers learn of her “Hispanic” identity—an identity that holds no room for Blackness.

“Let the record show. I am. Hispanic. Not Black. This is legal. A record.

Permanent.”

In much of Dominican culture, Dominicans' proximity to Haitian descent is often denied at all costs. Fear of Blackness plagues the island. The speaker recounts conversations with her mother in which she asks, “Are you sure we’re not Haitian?” to which her mother’s hand “recoils”. This tension reverberates for generations, not only in the speaker's search for her own identity, but in her relationship with her daughter. The speaker contemplates that “[o]ne day my daughter will tell her daughter 'We were Black once'”. This discovery of truth is painted as an elusive light that can only shine far after those who could confirm it are dead and gone. However, it is the guttural and necessary calling that pushes the speaker deeper into accounting for the atrocities of history and the equally-dangerous omissions practiced by her own family.

The second section is a revised and reframed version of Mendez’s play of the same name. This piece first found its legs in a staged reading during the Sin Muros Play Festival hosted by Stages Theater in Houston, TX. Mendez serves as an organizer and contributor to the festival, which is dedicated to elevating the voices of up-and-coming Latine playwrights in and around the city. The play then ventured to the Milagro Theater in Portland, Oregon for a full production. While the Act-based structure is familiar, the use of dramaturgical notes, customizable design maps, text-based interludes, and Post Production notes make space for even more in-depth commentary than a stage could offer. The play follows five Haitian citizens, the author, a soldier in General Rafael Trujillo’s army, and the most powerful vessel, the Machete as a snapshot of their lives in Dajabón, Dominican Republic. While their everyday existence seems as simple as “An empty altar” and “The sound of running water”, quickly there is an apparent threat in the ways that the world has silenced the records and impact of this massacre.

“America didn’t care about us as a news story.

And in a hospital along the border,

Men, women, and children laid severed

Limb stumps pulsing angry red against black skin…

Whole families fleshed by the flashing fury of a machete.”

Historians estimate between 9,000 and 20,000 Haitians were killed in the violent massacre set off by General Trujillo to “remedy the situation” of Haitian existence. And while this atrocity itself deserves more coverage, Mendez doesn’t settle on only bringing it to light. Instead, she uses interjected x-rays of her constantly changing hands over the course of multiple amputations to draw readers into a conversation about identity and sacrifice:

“My wounds will be made by a scalpel. Not a machete. But I too will be cut. Pieces of me will go missing. Where will they end up? When a foreign substance invades the body, the body attacks it… But what happens when the body attacks itself? How do you heal when you are the weapon and the wound?”

Mendez, who battles Scleroderma, an auto-immune condition which causes hardening and tightening of the skin, and which can result in ulcers, blood conditions, and inflammation, offers her personal struggle as a vehicle to examine civil war and belonging. In the same ways that her own body battles to gain ground with itself, the island region that holds the Dominican Republic and Haiti war for more power; two identities that Mendez also finds herself trapped between.

“I am a fork in the road. Half of me here. Half of me there.”

Mendez jostles to find space for her physical body and the trauma of disfigurement. In the same ways that the survivors of Trujillo’s killings silently carry the stories of what they witnessed, the speaker carries the weight of being forced to sacrifice part of herself to keep other parts living. Both parts, heavy and laden with loss and sacrifice; both seeking ways to honor the past and move into a better future.

The future is exactly where Mendez settles for her third and final section of this collection. Taking a sharp turn from violent and painful realities of war and self-sacrifice, Mendez arrives as mother—one who grapples with her own physical limitations, grief, and new responsibility of raising a daughter in a threatening world.

“She sits in a bathtub…She can think in here… She’ll study the length of her own nails. Her hair legs. Her arms. And how much they have to carry. To reach for. She’ll rub her back. Hips. Thighs. Breasts. Remember when they belonged only to her.”

It is in this intimate future that all things are reconciled. Not by a pretty bow or a perfect ending, but by an acceptance of the things she cannot change and the history she cannot undo. Mendez finds a way to insist that the speaker's trauma and the sacrifices of her ancestors be not in vain, by continuing to create life. It is a revolutionary act of existing in a country that doesn’t want you. It is finding joy in a life that only wants to offer heartache. Jasminne Mendez finds a way to serve triumph from a plate of trauma with a silver spoon, a metaphor she uses towards the end of the book in “ Silver Spoon”:

“You reach for the silver spoon. I let you. Hold it. I let you feel what it feels like. In your unsteady hands. You lift it up to your nose. Nope. That’s not right. You lift it up to your eyes. Still too high. You lower it down to your chin. You’ve made a mess. All over. Your face. I do not wipe it away. We laugh.”

Her daughter becomes a balm that offers a passageway to a brighter future. And in the way that we are our ancestor’s wildest dreams, this “lullaby that trembles on the tongue and kicks at the teeth” becomes a “[l]ight that slips in even after the final curtain is closed.” A light that every reader can follow to truth. To belonging.

City Without Altar shows readers how to traverse a difficult history without muting it for comfort. This book creates healing reconciliation between self and the art of sacrifice. It bends form into a kaleidoscope of self-examination and a celebration of truth, leaving readers bathed with compassion and with no room to hide from the light of healing.

For those of us who struggle with holding more than one marginalized identity, there is sometimes an impeding desire to choose one over the other. For example, the social need to label oneself forces us to decide on how the world will interact with us. However, there is a risk in removing one portion of oneself to save the other identity. There are casualties to every war, even one we fight with ourselves. This pull to find a neutral ground with one’s own identity is the guiding conflict that Jasminne Mendez wrestles with in her newest collection City Without Altar (Noemi Press, 2022).

Mendez is a Dominican-American poet, playwright, translator, and award-winning author of multiple books including Island of Dreams (Floricanto Press), Night-Blooming Jasmin(n)e: Personal Essays and Poetry (Arte Público Press), Islands Apart: Becoming Dominican American (Arte Público Press), and Josefina’s Habichuelas (Arte Público Press). This Cantomundo fellow and co-founder of the Houston based Latine literary arts organization, Tintero Projects, has dedicated her work to elevating Latine voices across the world. Identifying as Black, Latine, Disabled, and a Mother, Mendez's collection seeks to balance identities like no other. Finding parallels with the mutilation of the 1937 Haitian Massacre, Mendez examines her struggles with pregnancy, autoimmunity, and belonging. The collection is broken into three sections, consisting of prose and poems that flank either side of an interactive theatrical script. Readers are offered x-rays of Mendez’s hands throughout multiple medical procedures, interlaced around reports of General Trujilio “chopping” Haitians to death at the Dominican border. In addition, Mendez curates plot maps, lists, and fill-in-the-blanks to engage readers in the process of creating meaning from her text. She beckons readers to “lift up their names until someone else can hear it”.

The first section of the collection centers on omission. Opening with a black out poem created from Mendez’s birth certificate, readers learn of her “Hispanic” identity—an identity that holds no room for Blackness.

“Let the record show. I am. Hispanic. Not Black. This is legal. A record.

Permanent.”

In much of Dominican culture, Dominicans' proximity to Haitian descent is often denied at all costs. Fear of Blackness plagues the island. The speaker recounts conversations with her mother in which she asks, “Are you sure we’re not Haitian?” to which her mother’s hand “recoils”. This tension reverberates for generations, not only in the speaker's search for her own identity, but in her relationship with her daughter. The speaker contemplates that “[o]ne day my daughter will tell her daughter 'We were Black once'”. This discovery of truth is painted as an elusive light that can only shine far after those who could confirm it are dead and gone. However, it is the guttural and necessary calling that pushes the speaker deeper into accounting for the atrocities of history and the equally-dangerous omissions practiced by her own family.

The second section is a revised and reframed version of Mendez’s play of the same name. This piece first found its legs in a staged reading during the Sin Muros Play Festival hosted by Stages Theater in Houston, TX. Mendez serves as an organizer and contributor to the festival, which is dedicated to elevating the voices of up-and-coming Latine playwrights in and around the city. The play then ventured to the Milagro Theater in Portland, Oregon for a full production. While the Act-based structure is familiar, the use of dramaturgical notes, customizable design maps, text-based interludes, and Post Production notes make space for even more in-depth commentary than a stage could offer. The play follows five Haitian citizens, the author, a soldier in General Rafael Trujillo’s army, and the most powerful vessel, the Machete as a snapshot of their lives in Dajabón, Dominican Republic. While their everyday existence seems as simple as “An empty altar” and “The sound of running water”, quickly there is an apparent threat in the ways that the world has silenced the records and impact of this massacre.

“America didn’t care about us as a news story.

And in a hospital along the border,

Men, women, and children laid severed

Limb stumps pulsing angry red against black skin…

Whole families fleshed by the flashing fury of a machete.”

Historians estimate between 9,000 and 20,000 Haitians were killed in the violent massacre set off by General Trujillo to “remedy the situation” of Haitian existence. And while this atrocity itself deserves more coverage, Mendez doesn’t settle on only bringing it to light. Instead, she uses interjected x-rays of her constantly changing hands over the course of multiple amputations to draw readers into a conversation about identity and sacrifice:

“My wounds will be made by a scalpel. Not a machete. But I too will be cut. Pieces of me will go missing. Where will they end up? When a foreign substance invades the body, the body attacks it… But what happens when the body attacks itself? How do you heal when you are the weapon and the wound?”

Mendez, who battles Scleroderma, an auto-immune condition which causes hardening and tightening of the skin, and which can result in ulcers, blood conditions, and inflammation, offers her personal struggle as a vehicle to examine civil war and belonging. In the same ways that her own body battles to gain ground with itself, the island region that holds the Dominican Republic and Haiti war for more power; two identities that Mendez also finds herself trapped between.

“I am a fork in the road. Half of me here. Half of me there.”

Mendez jostles to find space for her physical body and the trauma of disfigurement. In the same ways that the survivors of Trujillo’s killings silently carry the stories of what they witnessed, the speaker carries the weight of being forced to sacrifice part of herself to keep other parts living. Both parts, heavy and laden with loss and sacrifice; both seeking ways to honor the past and move into a better future.

The future is exactly where Mendez settles for her third and final section of this collection. Taking a sharp turn from violent and painful realities of war and self-sacrifice, Mendez arrives as mother—one who grapples with her own physical limitations, grief, and new responsibility of raising a daughter in a threatening world.

“She sits in a bathtub…She can think in here… She’ll study the length of her own nails. Her hair legs. Her arms. And how much they have to carry. To reach for. She’ll rub her back. Hips. Thighs. Breasts. Remember when they belonged only to her.”

It is in this intimate future that all things are reconciled. Not by a pretty bow or a perfect ending, but by an acceptance of the things she cannot change and the history she cannot undo. Mendez finds a way to insist that the speaker's trauma and the sacrifices of her ancestors be not in vain, by continuing to create life. It is a revolutionary act of existing in a country that doesn’t want you. It is finding joy in a life that only wants to offer heartache. Jasminne Mendez finds a way to serve triumph from a plate of trauma with a silver spoon, a metaphor she uses towards the end of the book in “ Silver Spoon”:

“You reach for the silver spoon. I let you. Hold it. I let you feel what it feels like. In your unsteady hands. You lift it up to your nose. Nope. That’s not right. You lift it up to your eyes. Still too high. You lower it down to your chin. You’ve made a mess. All over. Your face. I do not wipe it away. We laugh.”

Her daughter becomes a balm that offers a passageway to a brighter future. And in the way that we are our ancestor’s wildest dreams, this “lullaby that trembles on the tongue and kicks at the teeth” becomes a “[l]ight that slips in even after the final curtain is closed.” A light that every reader can follow to truth. To belonging.

City Without Altar shows readers how to traverse a difficult history without muting it for comfort. This book creates healing reconciliation between self and the art of sacrifice. It bends form into a kaleidoscope of self-examination and a celebration of truth, leaving readers bathed with compassion and with no room to hide from the light of healing.

Deborah D.E.E.P. Mouton is an internationally-known writer, educator, activist, performer, and the first Black Poet Laureate of Houston, Texas. Formerly ranked the #2 Best Female Performance Poet in the World, her recent poetry collection, Newsworthy, garnered her a Pushcart nomination, was named a finalist for the 2019 Writer’s League of Texas Book Award, and received honorable mention for the Summerlee Book Prize. Its German translation, under the title "Berichtenswert," is set to be released in Summer 2021 by Elif Verlag. She lives and creates in Houston, TX. For more information visit www.LiveLifedeep.com.