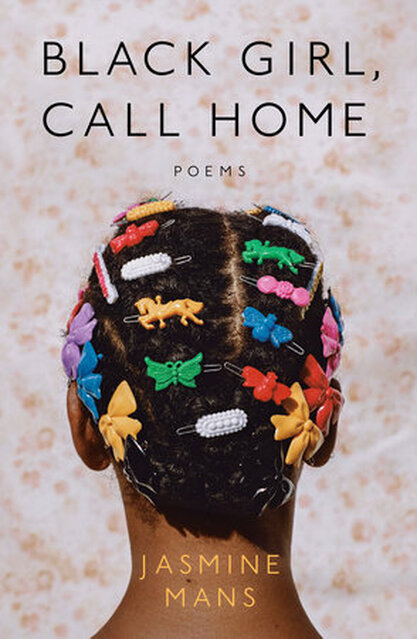

Black Girl, Call Home by Jasmine Mans

Reviewed by Deborah D.E.E.P. Mouton

“What’ does it mean

I keepeth my sister?

That I hold on to her

And love her in ugly,

Rotten, uncertainty.”

(From “My Sister’s Keeper”)

I have often been struck by the ways that history and the media have tried to categorize Black women. Whether it be by prejudging us by our hair or limiting any emotional outburst to tropes and stereotypes, Black women often find themselves in flat depictions that do not allow room for more than one emotion at a time. It is this kind of limitation that Jasmine Mans is undoing in her second poetry collection, Black Girl, Call Home (Penguin Random House, 2021).

Black Girl, Call Home offers no apologies for echoing the complex voice of Black womanhood. It forces readers to embrace the multifaceted experience of these women by thrusting them into a world where vulnerability, wisdom, and discovery converge. Mans effortlessly blends the voices of the young and old, the fearful and fearless, into an elegant love letter to the Black woman herself. Her depiction of sexuality, religion, and the dangers of taking up too much space, resonate far beyond any confines of a monolith.

It is through lyrical, accessible free verse, haikus, odes, mind maps, word searches and lists that Mans reminds the readers that Black womanness is not limited to one presentation. Rather, she opens an opportunity for readers to discover more about themselves in her own self-discovery across multiple forms. The structure of this book doesn’t hinge on traditional separation by chapter or theme. Instead, Mans offers a more unpredictable revisitation of sexuality, societal danger, moments with her mother, and contemplations of death, or the fear of it. Man’s plays with poem lengths to maximize impact, sandwiching everything from multi-paged poems that feel like they were ripped from her onstage performances to single line reflections, like “Don’t come inside me looking for nothing”, that pack an equally potent punch. It is through this onion-like organization that the speaker of Man's collection peels back layers of herself to uncover what it means to love and be loved.

Mans seems to come of age between each poem in this collection. When we first meet her, she is young and impressionable. She stumbles through her mother's presumptions on beauty and what it is to be “an acceptable woman” From spending hours taming their hair to Sunday’s spent thoroughly cleaning the house, the young girl in her watches as her mother attempts to convince God of her worthiness.

“That was her way of showing God

That she had a servant’s heart,

That she was a good woman,

With all of the little

she had.”

It is this expectation to please everyone around her, including her god, that is bent on ensuring her ability to make a proper macaroni and cheese and how to avoid “being a dyke.” For the mother in us wants to save our children from harm even at the risk of harming them ourselves. And while the girl longs for the acceptance of her mother, she also finds herself constrained by her mother's antiquated methods of survival.

“Before my mother knew

I was a lesbian

She prepared me

To be a man’s wife.”

It is at this crossroad that Mans begins to unpack another layer of experience: sexuality in the eyes of religion. This rumination on loving someone of the same gender grows with every relationship the girl experiences. As she falls more freely in love with women, she finds herself more freely in love with herself. Yet, in accepting this, she drifts farther from her mother’s god; a god that “only knows us by our flesh.” This God seems to play witness to many horrors. From rape to medical experimentation to the assault on trans women’s lives, there seems to be an absence of divine intervention.

“My heart sits heavy thinking about the women who could not run out of

their hospital rooms, the women who lay paralyzed, waiting to heal, or to

die. And for that woman, who lay waiting to heal, who was her God?"

Mans’ questioning of God doesn’t just live in societal terrors, but as she ages and falls in love with a woman, her understanding of the divine becomes even more strenuous. She offers up a confusing god. One who can allow love to grow between two women, but hates when they embrace it for themselves. This haunting contradiction forces the young lady to revert to her girlish musings. She delays embracing her sexuality for fear that she would be less holy. This is where Mans uses repetition and reinserted themes to bring in remnants of her young and wandering voice As if to say that there is always a girl within us trying to figure herself out. And while consumed by her desire to reckon with this internal conflict, she finds herself still tasked with processing the world around her.

Fear begins to echo through Mans’ poems as they examine all of the ways that Black women’s environments have tried to harm them. From describing the bombing of the 13th street Baptist church in “Birmingham” to an entire section dedicated to Whitney Houston, Mans shows us how racism and violence has no respect for fame.

“You don’t have to be alive

To make a living,

Or a killing.”

It is in these poems such as this that Mans’ eyes for social commentary and history as a spoken word artist emerge. Her longer poems seem more rhythmic, urging us to read them aloud from the page, as if conjuring familiar names like Kanye West, Bill Cosby, and Serena Williams will pull them off of their celebrity pedestals and make them more fallible. These multi-page odes seem to hold all the secrets behind the cloud of popular opinion. They wrestle with grief in the most intimate way. They show the reader how the world has disappointed their idols as much as their idols have disappointed them. They remind us that the dangers of being Black do not stop because you are popular and talented. In fact, they increase. The world seems to hold its breath for “a star falling aimlessly towards the concrete.” In fact, it “demand(s) an encore.” It anticipates the “most favorite tragedy”, whether it comes at the hands of the police or our own failing mental health.

Despite living in all of this “rotten uncertainty” of life, Mans grounds uses her relationships to cleave onto her own truth. As the young lady in her becomes a wise and determined woman, she begins to accept the world she cannot change and seeks to truly find a permanent place in it. For Mans, this truth means being free to permanently accept herself within a queer relationship.

“You have lines on your breasts

That make me want to write…

I won’t leave”

She begins to let go of all of people’s expectations, including her mother’s, and truly gives into love.

“I will love you

Even after

You change your mind

About me.”

This love is one that beams from a love of self. This love allows her to make room for romance, to become her sister’s keeper, and to be a woman can now return to prayer with a new perspective.

When Mans’ pulls the reader back to God, this time, it is not to embrace the religion of her mother. This is a benevolent God that “stores (her prayers) in the front of his Levi’s.” One who “rereads (her) for the joy.” She offers readers a journey that teaches us that Black women have a redemptive story worth telling. She urges us to extend forgiveness, even to ourselves. She offers us a way to find love, unbridled by gender. She reminds us that “God leaves stretch marks on women to direct us home.” At every turn, despite all the things stacked against them, Black women find a soft place to land. Even if it is just by calling home.

I keepeth my sister?

That I hold on to her

And love her in ugly,

Rotten, uncertainty.”

(From “My Sister’s Keeper”)

I have often been struck by the ways that history and the media have tried to categorize Black women. Whether it be by prejudging us by our hair or limiting any emotional outburst to tropes and stereotypes, Black women often find themselves in flat depictions that do not allow room for more than one emotion at a time. It is this kind of limitation that Jasmine Mans is undoing in her second poetry collection, Black Girl, Call Home (Penguin Random House, 2021).

Black Girl, Call Home offers no apologies for echoing the complex voice of Black womanhood. It forces readers to embrace the multifaceted experience of these women by thrusting them into a world where vulnerability, wisdom, and discovery converge. Mans effortlessly blends the voices of the young and old, the fearful and fearless, into an elegant love letter to the Black woman herself. Her depiction of sexuality, religion, and the dangers of taking up too much space, resonate far beyond any confines of a monolith.

It is through lyrical, accessible free verse, haikus, odes, mind maps, word searches and lists that Mans reminds the readers that Black womanness is not limited to one presentation. Rather, she opens an opportunity for readers to discover more about themselves in her own self-discovery across multiple forms. The structure of this book doesn’t hinge on traditional separation by chapter or theme. Instead, Mans offers a more unpredictable revisitation of sexuality, societal danger, moments with her mother, and contemplations of death, or the fear of it. Man’s plays with poem lengths to maximize impact, sandwiching everything from multi-paged poems that feel like they were ripped from her onstage performances to single line reflections, like “Don’t come inside me looking for nothing”, that pack an equally potent punch. It is through this onion-like organization that the speaker of Man's collection peels back layers of herself to uncover what it means to love and be loved.

Mans seems to come of age between each poem in this collection. When we first meet her, she is young and impressionable. She stumbles through her mother's presumptions on beauty and what it is to be “an acceptable woman” From spending hours taming their hair to Sunday’s spent thoroughly cleaning the house, the young girl in her watches as her mother attempts to convince God of her worthiness.

“That was her way of showing God

That she had a servant’s heart,

That she was a good woman,

With all of the little

she had.”

It is this expectation to please everyone around her, including her god, that is bent on ensuring her ability to make a proper macaroni and cheese and how to avoid “being a dyke.” For the mother in us wants to save our children from harm even at the risk of harming them ourselves. And while the girl longs for the acceptance of her mother, she also finds herself constrained by her mother's antiquated methods of survival.

“Before my mother knew

I was a lesbian

She prepared me

To be a man’s wife.”

It is at this crossroad that Mans begins to unpack another layer of experience: sexuality in the eyes of religion. This rumination on loving someone of the same gender grows with every relationship the girl experiences. As she falls more freely in love with women, she finds herself more freely in love with herself. Yet, in accepting this, she drifts farther from her mother’s god; a god that “only knows us by our flesh.” This God seems to play witness to many horrors. From rape to medical experimentation to the assault on trans women’s lives, there seems to be an absence of divine intervention.

“My heart sits heavy thinking about the women who could not run out of

their hospital rooms, the women who lay paralyzed, waiting to heal, or to

die. And for that woman, who lay waiting to heal, who was her God?"

Mans’ questioning of God doesn’t just live in societal terrors, but as she ages and falls in love with a woman, her understanding of the divine becomes even more strenuous. She offers up a confusing god. One who can allow love to grow between two women, but hates when they embrace it for themselves. This haunting contradiction forces the young lady to revert to her girlish musings. She delays embracing her sexuality for fear that she would be less holy. This is where Mans uses repetition and reinserted themes to bring in remnants of her young and wandering voice As if to say that there is always a girl within us trying to figure herself out. And while consumed by her desire to reckon with this internal conflict, she finds herself still tasked with processing the world around her.

Fear begins to echo through Mans’ poems as they examine all of the ways that Black women’s environments have tried to harm them. From describing the bombing of the 13th street Baptist church in “Birmingham” to an entire section dedicated to Whitney Houston, Mans shows us how racism and violence has no respect for fame.

“You don’t have to be alive

To make a living,

Or a killing.”

It is in these poems such as this that Mans’ eyes for social commentary and history as a spoken word artist emerge. Her longer poems seem more rhythmic, urging us to read them aloud from the page, as if conjuring familiar names like Kanye West, Bill Cosby, and Serena Williams will pull them off of their celebrity pedestals and make them more fallible. These multi-page odes seem to hold all the secrets behind the cloud of popular opinion. They wrestle with grief in the most intimate way. They show the reader how the world has disappointed their idols as much as their idols have disappointed them. They remind us that the dangers of being Black do not stop because you are popular and talented. In fact, they increase. The world seems to hold its breath for “a star falling aimlessly towards the concrete.” In fact, it “demand(s) an encore.” It anticipates the “most favorite tragedy”, whether it comes at the hands of the police or our own failing mental health.

Despite living in all of this “rotten uncertainty” of life, Mans grounds uses her relationships to cleave onto her own truth. As the young lady in her becomes a wise and determined woman, she begins to accept the world she cannot change and seeks to truly find a permanent place in it. For Mans, this truth means being free to permanently accept herself within a queer relationship.

“You have lines on your breasts

That make me want to write…

I won’t leave”

She begins to let go of all of people’s expectations, including her mother’s, and truly gives into love.

“I will love you

Even after

You change your mind

About me.”

This love is one that beams from a love of self. This love allows her to make room for romance, to become her sister’s keeper, and to be a woman can now return to prayer with a new perspective.

When Mans’ pulls the reader back to God, this time, it is not to embrace the religion of her mother. This is a benevolent God that “stores (her prayers) in the front of his Levi’s.” One who “rereads (her) for the joy.” She offers readers a journey that teaches us that Black women have a redemptive story worth telling. She urges us to extend forgiveness, even to ourselves. She offers us a way to find love, unbridled by gender. She reminds us that “God leaves stretch marks on women to direct us home.” At every turn, despite all the things stacked against them, Black women find a soft place to land. Even if it is just by calling home.

Deborah D.E.E.P. Mouton is an internationally-known writer, educator, activist, performer, and and the first Black Poet Laureate of Houston, Texas. Formerly ranked the #2 Best Female Performance Poet in the World, Her recent poetry collection, Newsworthy, garnered her a Pushcart nomination, was named a finalist for the 2019 Writer’s League of Texas Book Award, and received honorable mention for the Summerlee Book Prize. Its German translation, under the title "Berichtenswert," is set to be released in Summer 2021 by Elif Verlag. She lives and creates in Houston, TX. For more information visit www.LiveLifedeep.com