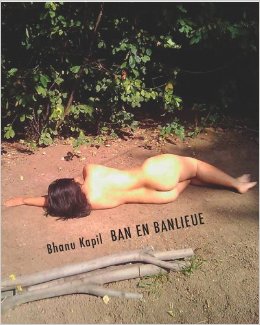

Ban en Banlieue by Bhanu Kapil

Reviewed by Lindsay King-Miller

“It is so excruciating to write about these subjects that I take years, months: to write them,” explains Bhanu Kapil in her fifth book, Ban en Banlieue (Nightboat Books). Many books are categorized as “experimental” because they don’t fit into the clear boundaries of poetry and prose, fiction and nonfiction, but few deserve the label more than Ban en Banlieue, which is less a straightforward story than a gravesite haunted by a story that might have been.

At the center of Ban en Banlieue’s collection of notes, story fragments, and prose poems is a young girl named Ban who gets caught in a race riot while walking home from school in England in 1979. The riot is real. The girl is fictional. The story is ultimately unspeakable. Ban en Banlieue is Kapil’s way of explaining why she could not write the book she initially set out to write: the book of Ban. “And this was what happened when the project fell away and all I was left with were the materials themselves,” Kapil writes in “13 Errors for Ban,” the second piece in the book by that title, a series of notes on the author’s various attempts to bring the book of Ban into existence.

Though Kapil does not fully explain why the book as it was originally conceived could not be completed, there are hints throughout, places where the awareness of the trauma being described supersedes the author’s ability to describe that trauma. In “Paranoia and the body,” she writes, “I want to think about the body becoming a kind of food for the street. Irreducible.” Ban en Banlieue is a book about violence, specifically racial and sexual violence, as enacted on the bodies of both victims and bystanders. Perhaps the book could not be written because the real, historical violence at its core could not be flattened into any kind of fictional shape, a satisfying narrative arc.

Along with the ghost of the novel that could not be written, Ban en Banlieue is inhabited by the memories of Blair Peach, an anti-racist activist killed in the 1979 race riot, and Jyoti Singh Pandey, who was raped and murdered by a group of men on a bus in Delhi in 2012. Of Peach, Kapil writes, “He is the martyr of my novel although he does not appear in it. He appears here. He appears now. He appears before the novel begins,” but it is clear that the novel has already begun–that it began long before the reader came along. These inhumanities are both the reason the novel must be written and the reason it can never be completed, the violent reality obliterating artistic potential. “I made a mark in the dirt where something was,” writes Kapil in “Chrysalis Notes, India,” and it’s almost a summary of Ban en Banlieue – the mark is not, and never can be, the “something” in the dirt.

The book begins in the middle, with Kapil noting a missing piece in the narrative she is writing, which the audience understands is ongoing though it has just been introduced: “At that moment, I realize I have not written the part of Ban that is about sex–the bad sex of the riot.” Though Ban en Banlieue is more a series of gaps and elisions than a cohesive narrative, the way these gaps are arranged gives the reader a strong sense of aftermath–of understanding what has happened based on the mess left behind. Kapil writes and unwrites the story of Ban, negotiating when and how violence is excused, and why some bodies are deemed acceptable victims. She writes, “The project fails at every instant and you can make a book out of that and I do.”

Ban en Banlieue is less concerned with overarching structure than it is with tiny moments and objects–debris, gestures, tiny rituals. These things, described in the book as “auto-sacrifice,” stand-in for more obvious and expected novel components like characters, subplots, a denouement. “Invert yourself above a ditch or stream below a bright blue sky,” writes Kapil in “Meat forest: 1979.” “Then pull yourself up from your knees to clean.” This is one of many direct instructions to the reader throughout Ban en Banlieue, intended perhaps as ways of accessing the emotional content of the story, spells to invoke Ban who never was.

Kapil focuses on everyday details–grime, flowers–but renders them alien through unexpected juxtaposition and the surreal intrusion of fiction onto reality. “Is there a copper wire? Is there a groin? Make a mask for Ban.” The way Kapil uses language is always strange, always surprising, always interrupting what the reader expects. Pauses occur in odd places. Words repeat themselves and twist and acquire or accrue new sensations. Kapil writes, “I wanted to write a book that was like lying down. That took some time to write, that kept forgetting something, that took a diversion: from which it never returned.” Ban en Banlieue is this diversion, never circling back to its source.

It’s always difficult to explain or describe what’s happening in a Bhanu Kapil book, and that has never been truer than it is of Ban en Banlieue. You have to read it to understand. You have to follow all the traces, the clues, the treasure map that you think will lead you to Ban but that always leads you somewhere else. In the book’s final piece (poem? Letter? Gesture?), titled “Mermaid Series for Ban,” Kapil writes, “I feel bad for you, having read this far into the nothing that these notes are.” But Ban en Banlieue is not nothing. It’s a story without a conventional structure, but that doesn’t make it meaningless. By leading the reader through the process of trying to create an impossible book, Kapil teaches them to write it themselves. Ban becomes all the more real because she is indescribable. This book is scattered bones. The job of the reader is to examine them and imagine how they might fit together into some new kind of body.

At the center of Ban en Banlieue’s collection of notes, story fragments, and prose poems is a young girl named Ban who gets caught in a race riot while walking home from school in England in 1979. The riot is real. The girl is fictional. The story is ultimately unspeakable. Ban en Banlieue is Kapil’s way of explaining why she could not write the book she initially set out to write: the book of Ban. “And this was what happened when the project fell away and all I was left with were the materials themselves,” Kapil writes in “13 Errors for Ban,” the second piece in the book by that title, a series of notes on the author’s various attempts to bring the book of Ban into existence.

Though Kapil does not fully explain why the book as it was originally conceived could not be completed, there are hints throughout, places where the awareness of the trauma being described supersedes the author’s ability to describe that trauma. In “Paranoia and the body,” she writes, “I want to think about the body becoming a kind of food for the street. Irreducible.” Ban en Banlieue is a book about violence, specifically racial and sexual violence, as enacted on the bodies of both victims and bystanders. Perhaps the book could not be written because the real, historical violence at its core could not be flattened into any kind of fictional shape, a satisfying narrative arc.

Along with the ghost of the novel that could not be written, Ban en Banlieue is inhabited by the memories of Blair Peach, an anti-racist activist killed in the 1979 race riot, and Jyoti Singh Pandey, who was raped and murdered by a group of men on a bus in Delhi in 2012. Of Peach, Kapil writes, “He is the martyr of my novel although he does not appear in it. He appears here. He appears now. He appears before the novel begins,” but it is clear that the novel has already begun–that it began long before the reader came along. These inhumanities are both the reason the novel must be written and the reason it can never be completed, the violent reality obliterating artistic potential. “I made a mark in the dirt where something was,” writes Kapil in “Chrysalis Notes, India,” and it’s almost a summary of Ban en Banlieue – the mark is not, and never can be, the “something” in the dirt.

The book begins in the middle, with Kapil noting a missing piece in the narrative she is writing, which the audience understands is ongoing though it has just been introduced: “At that moment, I realize I have not written the part of Ban that is about sex–the bad sex of the riot.” Though Ban en Banlieue is more a series of gaps and elisions than a cohesive narrative, the way these gaps are arranged gives the reader a strong sense of aftermath–of understanding what has happened based on the mess left behind. Kapil writes and unwrites the story of Ban, negotiating when and how violence is excused, and why some bodies are deemed acceptable victims. She writes, “The project fails at every instant and you can make a book out of that and I do.”

Ban en Banlieue is less concerned with overarching structure than it is with tiny moments and objects–debris, gestures, tiny rituals. These things, described in the book as “auto-sacrifice,” stand-in for more obvious and expected novel components like characters, subplots, a denouement. “Invert yourself above a ditch or stream below a bright blue sky,” writes Kapil in “Meat forest: 1979.” “Then pull yourself up from your knees to clean.” This is one of many direct instructions to the reader throughout Ban en Banlieue, intended perhaps as ways of accessing the emotional content of the story, spells to invoke Ban who never was.

Kapil focuses on everyday details–grime, flowers–but renders them alien through unexpected juxtaposition and the surreal intrusion of fiction onto reality. “Is there a copper wire? Is there a groin? Make a mask for Ban.” The way Kapil uses language is always strange, always surprising, always interrupting what the reader expects. Pauses occur in odd places. Words repeat themselves and twist and acquire or accrue new sensations. Kapil writes, “I wanted to write a book that was like lying down. That took some time to write, that kept forgetting something, that took a diversion: from which it never returned.” Ban en Banlieue is this diversion, never circling back to its source.

It’s always difficult to explain or describe what’s happening in a Bhanu Kapil book, and that has never been truer than it is of Ban en Banlieue. You have to read it to understand. You have to follow all the traces, the clues, the treasure map that you think will lead you to Ban but that always leads you somewhere else. In the book’s final piece (poem? Letter? Gesture?), titled “Mermaid Series for Ban,” Kapil writes, “I feel bad for you, having read this far into the nothing that these notes are.” But Ban en Banlieue is not nothing. It’s a story without a conventional structure, but that doesn’t make it meaningless. By leading the reader through the process of trying to create an impossible book, Kapil teaches them to write it themselves. Ban becomes all the more real because she is indescribable. This book is scattered bones. The job of the reader is to examine them and imagine how they might fit together into some new kind of body.