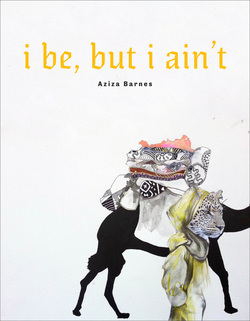

i be, but i ain't by Aziza Barnes

Reviewed by Corrina Bain, Book Reviewer

YesYes Books, 2016

YesYes Books, 2016

Let’s take a moment, before we go anywhere, to look at the title of Aziza Barnes’ debut full-length poetry collection, i be, but i ain’t (YesYes Books, 2016). It contradicts itself, with certainty. It elevates the “ain’t.” It declares itself as a complete thought and floats like a fragment. It is a perfect naming of this book, which puts the reader inside of a celebration, which is also a kind of dirge. The sections of the book are demarcated with quotes from Confederate General Stonewall Jackson. Beyond the initial delight this reappropriation and juxtaposition provokes, the Stonewall Jackson epigraphs also perform an important function. They place these fiercely contemporary poems in a context, like the idea of America itself, larger than life, at war with itself, somewhere between the historic and the biblical.

From the opening poem, (entitled “how to kill a house centipede by squishing it behind a photo of Miriam Makeba while contemplating various iterations of rigor mortis in my gentrified apartment complex on 750 macdonough street Brooklyn, ny11223”), Barnes gives us language that is balanced between joy and mourning, between mundane and mythic. The emergence of the centipede (“some design even violent with symmetry... is there a nest of these? a hive of these?”) heralds the speaker’s reflection on mortality (“the body/ defeated or the body striving") into a kind of orienting of the poem against Makeba ("a woman who was/ often not allowed to leave or forced to stay very far from where she began”). Then, having built this associative world of death and saints and contemporary American Blackness against the backdrop of South Africa and the diaspora, Barnes closes with the astonishing turn:

… understand I thought a colonizer’s thought

not “I’m sorry” or “I shouldn’t have killed it” but “if I don’t kill it

now, how will I find it again?”

All of this comes at the reader fast, at times conversational, at times discursive, and at every moment dizzyingly alive. There are parts of the book that feel like a good conversation with a charming, intense person at a party. And it is a special pleasure when the several directions and languages of the poem then coalesce into a hard gem like “I thought a colonizer’s thought.” The colonizer’s gaze, that attitude towards the Black body, haunts this manuscript. For example, in the long sectional poem “descendants,” the speaker is part pleading against, part shit-talking their own mortality:

Whachu

know bout me?

I cover

I cover but my skin

stay screamin! Who dat anyway?

I’m nobody’s son! Watch me race gainst

nothing! Watch nothing win.

Barnes traces the close association of the human and the body, the human and the animal, throughout this book. Several of the poems are concerned with “the mutt” as an icon: bestial, liminal, hungry. The mutt is introduced in a brief, sharply engineered didactic poem, then reprised in “the mutt as mudbone,” voiced through the lens of Richard Pryor’s stand-up character. The gesture towards comedy is striking and evocative here. How often has the comedian been the only voice “mainstream” America would entertain, on the subject of race? The mutt’s simple language conveys hopelessness and vitality at once:

They done played me out. Done played me

out again. They done played me

For a fool. My mama done raised A Played

Out Me. They done me in

& out I go

The loping, simple language and humor in this poem serve as a foil for the emotion that comes through at other times, screaming, precise, incisive. For example, in “brown noise:"

…I know you are going

to leave me. ½ naked and barking. I know

you are going to drive me to a street without a name

and spit on the tender of my thigh…

… I am staring at a dog

her teats dragging

on the gravel. I am tired like that.

At the same time that Barnes uses the mutt to illustrate a kind of bestializaton of brown people, there is a parallel exploration of womanhood. Not straightforward love or identity politic poems, these explorations are poignant, nuanced, celebratory and mysterious by turns. In “the mutt looks at her polycystic ovaries on a sonogram,” Barnes writes:

The women

in my family grow tumors before

children. They miscarry.

They piss on what they want

to keep safe.

…

…. I won’t yield

& I won’t yield. I bear every officer.

I bear epithet and eulogy. I bear Crenshaw and 48th.

Though the body is present and vital in these poems, it does not feel like gender is a primary question of the work. I am a little hesitant to say that, since women writers of color often end up being shunted out of “women’s literature,” in a way that marginalizes them further. And there are moments of desire and cuntiness (can I say cunt in a review? I hope so) which are certainly specific to the speaker and the speaker’s attempts to connect with men. I don’t think that Barnes is avoiding gender; I think the is successful in presenting it as a skein running through a broader tapestry. I mean to say that the question of the body in this book extends beyond the woman’s body or the sexualized body, leading back to the mutt, back to the American construct of race, and the adjacent sense of violence and kinship.

The deeper truth Barnes is giving us is that the different struggles of the body are not actually extricable from each other, that illness and violence and longing and revulsion and race and sex all occupy the same physical space, within us. There are moments when the body seems held accountable for the pain that is inflicted on it: “betrayal on a cellular level,” Barnes calls it, whether the ailment is bullet wounds or PCOS. One facet of this troubled view of the body/self is rendered simply in Ode to the Flying Trash:

I look up & see a black plastic

bag knotted firmly. Not flag enuf to

wave. Not proud but caught. In a

tight spot. I’ve often felt that way

Let's end where we began, with the title. The line “I be, but I ain’t” occurs in “We have no Conception of Bastard,” a narrative poem with strong reverberations of Edmund’s bastard speech in Lear. The speaker of this poem plays Michael Jackson in Ghana. (And remember the Stonewall epigraphs? The layering here of Jackson upon Jackson.) The speaker/DJ is asked by one of the Ghanaians at the dance:

what is ‘black?’ & I regurgitated the sure-fire

cure to any slavery: black is I gonna go. I finna go. I go,

I be but I ain’t. I bastard.

I done walked with a name I couldn’t shake and now I gone.

The synthesis here of a sorrow, a stolen, interrupted history, and an inescapable, bodily joy draws me back to these poems again and again. Barnes is writing poems out at the edge of what our culture has a language for. This book tells the truth in the language of our time, never flinching from the breadth and complexity of voice that is required. Barnes teaches us the value of eschewing a comfortable, simple sentiment that falls short of the truth. And even when the truth is full of the violence and dissociation that swarms around us, Barnes also offers us the buoyancy and fierce joy that carries us through. These poems are a rich, brave gift.

From the opening poem, (entitled “how to kill a house centipede by squishing it behind a photo of Miriam Makeba while contemplating various iterations of rigor mortis in my gentrified apartment complex on 750 macdonough street Brooklyn, ny11223”), Barnes gives us language that is balanced between joy and mourning, between mundane and mythic. The emergence of the centipede (“some design even violent with symmetry... is there a nest of these? a hive of these?”) heralds the speaker’s reflection on mortality (“the body/ defeated or the body striving") into a kind of orienting of the poem against Makeba ("a woman who was/ often not allowed to leave or forced to stay very far from where she began”). Then, having built this associative world of death and saints and contemporary American Blackness against the backdrop of South Africa and the diaspora, Barnes closes with the astonishing turn:

… understand I thought a colonizer’s thought

not “I’m sorry” or “I shouldn’t have killed it” but “if I don’t kill it

now, how will I find it again?”

All of this comes at the reader fast, at times conversational, at times discursive, and at every moment dizzyingly alive. There are parts of the book that feel like a good conversation with a charming, intense person at a party. And it is a special pleasure when the several directions and languages of the poem then coalesce into a hard gem like “I thought a colonizer’s thought.” The colonizer’s gaze, that attitude towards the Black body, haunts this manuscript. For example, in the long sectional poem “descendants,” the speaker is part pleading against, part shit-talking their own mortality:

Whachu

know bout me?

I cover

I cover but my skin

stay screamin! Who dat anyway?

I’m nobody’s son! Watch me race gainst

nothing! Watch nothing win.

Barnes traces the close association of the human and the body, the human and the animal, throughout this book. Several of the poems are concerned with “the mutt” as an icon: bestial, liminal, hungry. The mutt is introduced in a brief, sharply engineered didactic poem, then reprised in “the mutt as mudbone,” voiced through the lens of Richard Pryor’s stand-up character. The gesture towards comedy is striking and evocative here. How often has the comedian been the only voice “mainstream” America would entertain, on the subject of race? The mutt’s simple language conveys hopelessness and vitality at once:

They done played me out. Done played me

out again. They done played me

For a fool. My mama done raised A Played

Out Me. They done me in

& out I go

The loping, simple language and humor in this poem serve as a foil for the emotion that comes through at other times, screaming, precise, incisive. For example, in “brown noise:"

…I know you are going

to leave me. ½ naked and barking. I know

you are going to drive me to a street without a name

and spit on the tender of my thigh…

… I am staring at a dog

her teats dragging

on the gravel. I am tired like that.

At the same time that Barnes uses the mutt to illustrate a kind of bestializaton of brown people, there is a parallel exploration of womanhood. Not straightforward love or identity politic poems, these explorations are poignant, nuanced, celebratory and mysterious by turns. In “the mutt looks at her polycystic ovaries on a sonogram,” Barnes writes:

The women

in my family grow tumors before

children. They miscarry.

They piss on what they want

to keep safe.

…

…. I won’t yield

& I won’t yield. I bear every officer.

I bear epithet and eulogy. I bear Crenshaw and 48th.

Though the body is present and vital in these poems, it does not feel like gender is a primary question of the work. I am a little hesitant to say that, since women writers of color often end up being shunted out of “women’s literature,” in a way that marginalizes them further. And there are moments of desire and cuntiness (can I say cunt in a review? I hope so) which are certainly specific to the speaker and the speaker’s attempts to connect with men. I don’t think that Barnes is avoiding gender; I think the is successful in presenting it as a skein running through a broader tapestry. I mean to say that the question of the body in this book extends beyond the woman’s body or the sexualized body, leading back to the mutt, back to the American construct of race, and the adjacent sense of violence and kinship.

The deeper truth Barnes is giving us is that the different struggles of the body are not actually extricable from each other, that illness and violence and longing and revulsion and race and sex all occupy the same physical space, within us. There are moments when the body seems held accountable for the pain that is inflicted on it: “betrayal on a cellular level,” Barnes calls it, whether the ailment is bullet wounds or PCOS. One facet of this troubled view of the body/self is rendered simply in Ode to the Flying Trash:

I look up & see a black plastic

bag knotted firmly. Not flag enuf to

wave. Not proud but caught. In a

tight spot. I’ve often felt that way

Let's end where we began, with the title. The line “I be, but I ain’t” occurs in “We have no Conception of Bastard,” a narrative poem with strong reverberations of Edmund’s bastard speech in Lear. The speaker of this poem plays Michael Jackson in Ghana. (And remember the Stonewall epigraphs? The layering here of Jackson upon Jackson.) The speaker/DJ is asked by one of the Ghanaians at the dance:

what is ‘black?’ & I regurgitated the sure-fire

cure to any slavery: black is I gonna go. I finna go. I go,

I be but I ain’t. I bastard.

I done walked with a name I couldn’t shake and now I gone.

The synthesis here of a sorrow, a stolen, interrupted history, and an inescapable, bodily joy draws me back to these poems again and again. Barnes is writing poems out at the edge of what our culture has a language for. This book tells the truth in the language of our time, never flinching from the breadth and complexity of voice that is required. Barnes teaches us the value of eschewing a comfortable, simple sentiment that falls short of the truth. And even when the truth is full of the violence and dissociation that swarms around us, Barnes also offers us the buoyancy and fierce joy that carries us through. These poems are a rich, brave gift.